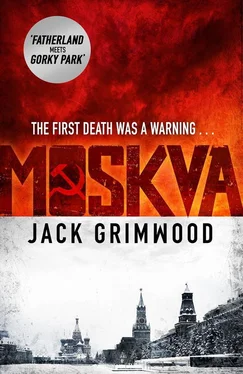

With the Soviets gone, the party relaxed.

Someone turned the lights down and the music up and a woman began chivvying couples on to the dance floor. Most were embarrassed but well aware there were still two hours to midnight. Abba gave way to Rod Stewart. Rod Stewart to Hot Chocolate… Not really Tom’s kind of music. He was thinking about going back to the balcony when he saw the ambassador lean in to the woman and mutter something. There was a manicured look about her as if she’d wandered in from Chelsea, and now found herself living in a Georgian rectory somewhere in Wiltshire and regretted the move.

She frowned but headed for Tom all the same.

‘It’s always hard,’ she said, ‘when you first arrive. If you don’t know anyone. We’re a friendly bunch really. Edward says your family will be joining you later.’

‘Possibly.’

Her smile faltered.

‘My wife’s having Christmas with her parents and Charlie’s back at school on the seventh. I might try to get back for half-term if I can.’

‘Charlie’s your son?’

Tom nodded.

‘Anna,’ she said, putting out her hand.

‘Lady Masterton?’

‘I prefer Anna.’

Her grip was as strong as her gaze was unfocused. ‘I couldn’t help noticing you glancing at my daughter earlier.’

‘Her dinner jacket is an interesting touch.’

Anna Masterton winced. ‘She’s cross with me.’

‘You in particular?’

‘Everyone really. It’s a difficult age.’

‘Seventeen?’

Anna Masterton didn’t know whether to be amused or appalled. ‘Is that what she told you? She’s sixteen next month.’

‘What’s she furious about?’

‘Lizzie went to Westminster for sixth form and Alex wanted to go too. Lizzie’s her friend. My husband wouldn’t let her. So now it’s a battle. An East German girl she met at the pool was having a party tonight. Edward said she had to come to this. Now he wants to drive out to Borodino, stay a few nights and walk the battlefield. Alex says he can’t make her. You can grin, but it’s bloody tiring.’

She spoke with the fierce intensity of the quietly drunk.

‘I’m sure it is,’ Tom agreed.

Anna Masterton shook her head, quite at what Tom wasn’t sure, and forced a smile more appropriate to an ambassador’s wife at an official function. ‘You’re a Russia expert, Edward says.’

‘I wouldn’t go that far.’

‘But you did lots of preparation for your visit here?’

‘I rewatched Andrei Rublev .’

She looked at him quizzically. ‘Isn’t that the strange black-and-white film with naked peasants in a forest setting fire to everything?’

‘Tarkovsky. 1966. It opens with a pagan festival.’

‘I thought Russia was Christian by then?’

‘Double faith,’ said Tom. ‘It’s called dvoeverie. Think of it as dual nationality for the unseen kingdoms.’

‘This is your area?’

‘That, and recognizing patterns in things. I’m here to write a report for the Foreign Office on religion in Russia.’

‘Isn’t that rather academic?’

‘If faith can move mountains, why shouldn’t it bring down a government?’

She looked round, realized her Soviet guests really had gone and lifted another glass of champagne from the tray of a passing waiter.

‘Do we want to bring their government down?’

‘Your husband’s more likely to know that than me.’

It wasn’t the real reason he was here, of course. He was here to keep him out of trouble. How much trouble he was in was being decided back in London. Meanwhile, to give his bosses a break, he was here.

Having made enough small talk to give him a headache, Tom pleaded the need for air and another cigarette. Skirting the dance floor entailed endless ‘excuse me’s as he made his way round the edge of the chocolate-box ballroom, with its white panels and gilding. As he went, he wondered what Caro was doing, then wished he hadn’t.

It would be teatime back home. She’d be on the sofa between her parents most likely, a fire already blazing in the hearth. The black-and-white portable wouldn’t be turned on until later. And even then it would have the sound down so no one had to pay it any attention until the chimes. Charlie would be getting ready for bed.

A brief protest at not being allowed up, then sleep and, with luck, no dreams.

A year from now…? His boy would still be in bed come New Year’s Eve. Probably still protesting, but not fiercely enough to make a difference. And Caro? Whoever’s bed she climbed into, Tom doubted it would be his. So why not give her what she wanted? It would be best for the boy. That was what she kept telling him. Charlie needs to know where he stands . ‘Bitch,’ Tom muttered.

‘Hey, that’s rude.’

It was the girl who’d begged a cigarette.

Tom blinked, ‘I’m sorry?’

‘I said that’s really rude.’

‘I wasn’t talking about you, obviously.’

‘ Obviously… ’ She did a passable imitation of Tom’s irritation.

‘People are watching,’ he said.

‘You think I care?’

‘No, I think that’s what you want.’

Her hair was wilder than before, her dinner jacket too tight to button. She’d folded up both sleeves since he last looked. Close to, he could see she was younger than he’d imagined. Her gaze found Sir Edward in the crowd and she smirked. ‘I’m going to tell my stepfather about you.’

Tom grabbed her as she turned.

The bones in her damaged wrist felt frighteningly fragile. Out of the corner of his eye, Tom saw the black woman he’d talked to earlier heading towards him and let the girl’s wrist drop. Her mother wasn’t the only one drunk around here.

‘Roll your sleeves down,’ he said, stepping back. ‘Or roll them up, let your parents see and have the damn argument. You’re obviously desperate for a fight.’

‘He’s not my parent.’

‘Whatever.’

Beneath her cuffs, not quite visible and not quite hidden, raw welts crossed both wrists. A blunt knife would do it.

‘What’s it got to do with you anyway?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Exactly.’

‘Wrist to elbow,’ he said. ‘Wrist to elbow. If you’re serious.’

Shrugging himself into his Belstaff, Tom left the party through high gates between wrought-iron railings mostly hidden by frosted trees. He made a point of nodding to the militsiya sergeant stamping his feet on the pavement outside. Brown coat, peaked cap, cheap boots, Makarov in a brown-leather holster.

Same poor sod as earlier.

Taking the metro would cost five kopeks, and the stations had such elegance they put London to shame, but Tom wanted to walk and if the little Russian assigned as Tom’s KGB shadow had to walk too, that was his bad luck.

From his pocket, Tom pulled a rabbit-fur cap bought that afternoon. It was second-hand and split along one edge. Cramming it on to his head, he lit a Russian cigarette and checked his reflection in a car window, flattering himself that he was safely anonymous, as drably dressed as those around him.

Just north of the Bolshoi and south of the Boulevard Ring that ran round inner Moscow, what Tom thought was a scraped-together mound of snow on the steps of a church shivered, and he stepped back as the mound shook itself from white to black, recently fallen flakes scattering to reveal an old woman.

A red scarf was tight around her head. She looked for a moment puzzled at where she found herself and then shrugged and examined the man in front of her with bright eyes. ‘American,’ she announced.

Tom shook his head.

‘Ah, he speaks Russian. Well, perhaps he knows the odd word.’ She looked beyond Tom to the crossroads, which was empty except for Tom’s shadow a hundred paces away, pretending to tie his shoe. Early twenties, skinny and rat-faced, he was putting in time as a pavement artist on his way to a nice warm desk from which he could order others to trawl around in the cold. Tom waved and received a scowl in reply.

Читать дальше

![Георгий Турьянский - MOSKVA–ФРАНКФУРТ–MOSKVA [Сборник рассказов 1996–2011]](/books/422895/georgij-turyanskij-moskva-frankfurt-moskva-sborni-thumb.webp)