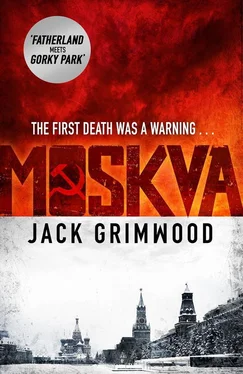

The alcohol would help, but it wasn’t enough to dull the rage at what some bastard had done to the poor bloody cat, and he knew he’d still be seeing its carcass hung above his sink as he tried to sleep.

He’d looked lonely in the cross hairs. So lonely that Wax Angel wondered if he’d welcome a bullet. When it came to it, people often did.

‘You…’

‘Me what?’

The militsiya man had looked sharply at her dishevelled state. So she’d glanced sharply back and made a point of buttoning the front of her dress. Only when he’d turned away did she return to the ancient Zeiss F-4 sniper’s sight she kept hidden in her clothing. It had been black once but in the last ten years its paint had begun to peel away in scabs. She still had the leather caps that fitted on either end though.

She’d watched the foreigner and his friend move through falling snow, his head down and his shoulders hunched, his thoughts a black cloud above him.

One hundred paces.

Two hundred paces.

If the snow had been heavy, she’d have lost him by now.

If the snow had really been falling, she’d have lost him before he travelled the distance of his own arm. At four hundred paces he’d begun to blur, vanishing at five. And Wax Angel realized the snow settling on her was camouflage. No need now for the white uniforms they’d worn and the sniper rifles wrapped in rags they’d carried through the smoking ruins of Stalingrad.

After the Englishman and his friend had gone, the coroner’s wagon had arrived. The woman driving had glanced over, made to turn away and then headed in Wax Angel’s direction. ‘Are you all right?’ she’d asked.

‘Yes, thank you,’ Wax Angel had said. ‘Are you?’

‘You must be freezing.’

‘This is nothing,’ Wax Angel said. ‘This is practically summer.’

‘Here.’ Digging into her jeans pocket, the woman had found a rouble. ‘Buy yourself something hot. You’ll buy food, right?’

She meant food rather than vodka.

Wax Angel was impressed that she left that part unsaid.

After the coroner’s office took the body, the militsiya man abandoned his post without sealing the ruin, or even putting tape across its door. How could Wax Angel not go to investigate? She found the burned-out building to her liking. There was something familiar, almost comfortable about its ruin.

Even better was a smouldering pile in one corner, with enough embers at the bottom to restart the fire once the rubble smothering it was dragged away.

Wax Angel spent a happy hour feeding the growing flames with every unburned scrap of wood she could find and then settled back to enjoy the warmth while snowflakes fluttered down in the sections of the warehouse where the roof had fallen away.

She could remember real blizzards, God wiping the face of the earth until everything was white.

She’d been younger then, of course. Much younger than the girl who’d given her money… And it was a long, long way from here. She’d been a campaign wife, but with a difference. Other ‘campaign wives’ were clerks or signallers. She was a sniper in her own right, dozens of kills to her record, her photograph in the army newspaper.

He was different too.

A political officer with actual battle experience.

He wasn’t one of those red-badged fools who screamed through a megaphone from the rear that everyone had to advance, that the Motherland was counting on them. He expected everyone to advance, right enough; he expected them to die. He just found that the walking dead fought better if talked to properly.

Not softly but firmly.

He’d been matter-of-fact about shooting anyone who tried to retreat.

It was the woman by the road Wax Angel remembered most.

They were beyond Breslau, with snow piled high against the hedges and a vicious wind ripping across the German fields and through the ruins of farmhouses destroyed in battle or burned by their owners before fleeing. She was young, the woman by the road. Her hair, in a thick blonde plait, was covered by a scarf too expensive to be any use against the cold. When Wax Angel found her she had her back to a hedge. Her skin was marble and her flesh as hard.

The baby at her frozen breast had died of cold, not hunger.

The men – heroes all – said what you’d expect.

All the houses were huge, palaces that turned out to belong to doctors and lawyers. Everyone had fridges. Most people had cars. More cars than anyone could imagine. At first their letters home were censored. Then they were burned in front of them. Finally, they’d been told that writing home would be forbidden if they kept exaggerating what they saw.

There’d been another nursing mother after Breslau.

Young and clear-skinned. Very German.

That had been later, after they’d won another battle.

The girl had been dragged into a church and raped throughout the day, the same men coming back hours later to take another turn. In the end, her grandfather had gone in tears to Wax Angel’s political officer. He’d begged him to make them stop; not for good, he knew that wouldn’t happen. Simply for long enough to let his granddaughter feed her child, which was hungry and wouldn’t stop crying.

Wax Angel shot the girls she saw after that.

The pretty ones first.

Such things happened because of Stalingrad.

Life expectancy for a new conscript was a day. Three days for a seasoned officer. Half a day for a junior lieutenant. She’d survived Stalingrad’s full seven and a half months. The lifespans of over two hundred men.

For Soviet citizens, a knock on the door at four in the morning traditionally indicates trouble for whoever quivers behind it, wondering whether to answer. But a knock on the door of an apartment in a block given over to foreigners? Tom took a Tokarev from his bedside cabinet, jacked the slide noisily enough for whoever was outside to hear and kept to one side as he undid the bolt.

As the door swung open, he grabbed the figure outside and hauled it into the apartment. Flicking on the overhead light, he found Anna Masterton glaring at him. Releasing the Tokarev’s clip, Tom dropped it out and would have put it in his dressing-gown pocket if he hadn’t suddenly realized he was naked. Squeezing the trigger, he supported the hammer with his thumb while it fell into place. He put the sidearm on the table beside the telephone, which began glowing red.

‘Why are you here?’ he asked.

‘Why are you naked?’

‘Anna, why are you here?’

‘You’re having an anxiety dream.’

The knock came a few minutes after Tom woke, as he stood in the flat’s tiny kitchen, boiling a kettle and staring at empty Carlsberg cans, filthy coffee cups and a slick of Vesta curry dried to a crust across the only unchipped plate in the place.

‘At least this time I’m wearing a dressing gown.’

Anna Masterton’s glance was wary.

‘I wanted to thank you,’ she said, ‘for letting me know the body was definitely not Alex. Your note said male, early twenties. Do I ask how you found out?’

‘A militsiya major from the investigator’s office south of the river on Novokuznetskaya Street lives locally and we drink in the same bar. I bought him a flask of vodka and he told me what I wanted to know.’

‘You make it sound so obvious.’

There was more, facts that Tom hadn’t put in his note.

The boy’s hands had been bound so tightly that his wrist fractured. Also, wounds exposing body fat burn at a different rate. In the coroner’s opinion the boy had been castrated. Given that his genitals had been cut away and his wrists bound tightly enough to crack bone, the balance of probability was that he’d been burned alive… Further tests could have proved that. But resources were tight, the department overworked and no one knew who he was anyway.

Читать дальше

![Георгий Турьянский - MOSKVA–ФРАНКФУРТ–MOSKVA [Сборник рассказов 1996–2011]](/books/422895/georgij-turyanskij-moskva-frankfurt-moskva-sborni-thumb.webp)