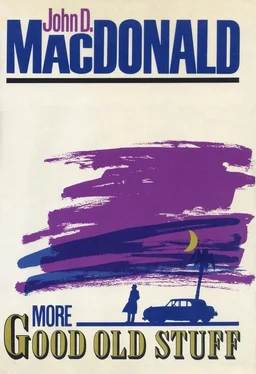

Джон Макдональд - More Good Old Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джон Макдональд - More Good Old Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1984, ISBN: 1984, Издательство: Alfred a Knopf, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:More Good Old Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:Alfred a Knopf

- Жанр:

- Год:1984

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-394-53898-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

More Good Old Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «More Good Old Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In short, here is one of America’s most gifted and prolific storytellers at his early best — a marvelously entertaining collection that will delight Mr. MacDonald’s hundreds of thousands of devoted readers.

More Good Old Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «More Good Old Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Now they’re out again!” Art called. “What are you guys doing down there?”

“Just a minute,” Stan yelled hoarsely. He tugged at Steve, rolled him over onto his face. The knife handle gritted against the cement floor. Stan got the flat automatic out of Steve’s hip pocket. He worked the slide, heard the clink of a round hitting the floor. He thumbed the safety off and went up the stairs.

As he stepped into the kitchen, he called back, “I’ll see if Art’s got one, Steve.”

He knocked against the doorframe, blundered into the dining room. “Say, Art, we need a penny to fix the fuse. You got one?”

“I hope you guys know what the hell you’re doing down there. The lights going off like that gives me the creeps. Did I hear Steve laughing?”

“Yeah. He was laughing. Now you can laugh, Art.”

“What are y—” That was all.

It was as though the slugs drove the breath out of Arthur Marka’s chest. The darkness stank of smokeless powder. Stan stood and listened. A heavy truck went by, and then two cars.

Slowly he exhaled. He lit a match, shook it out. Three in the chest and the last one in the face. Art was slumped in the chair, his chin on his chest, both arms hanging straight down.

In the darkness, Stan pushed him off the chair. He hit with a sodden, dead sound. Stan found his heels, dragged him to the cellar stairs, got behind him and pushed. Art Marka’s body rolled noisily down the steep flight, thudded against the cement at the bottom.

He turned out the cellar light, went up to his room, saving the money until last. He packed his few clothes, walked through the darkened house to the back door. Very simple. Two suitcases on the kitchen floor. One full of money. All for Stanley Ryan.

The car was gassed up. Lock the door and leave. The clothes and the carriage were in and the front door was locked.

Three feet from his head the bell shrilled. He started violently, stood shaking in the darkness. He cursed. Crouching, he ran to the front of the house, looked cautiously out the front-room window.

A white trooper car was parked in front, the motor running.

Caught like a rat in a trap.

He slipped out of his coat, threw it aside, transferring the gun to the right-hand pocket of his trousers. With trembling fingers, he unbuttoned his shirt down the front.

He turned on the hall light, opened the front door, yawning, and said, “What do you want?”

Two tall troopers stood there, and behind them, her eyes wide, stood the thin woman who had paid a call in the middle of the afternoon.

The trooper nearest the door looked disgusted. “Mister, we got funny stories and we have to look into them.”

“He’s the one! He’s the one!” the woman said shrilly.

“Yeah, lady. We know. Mister, I understand your wife is sick. Is that right?”

Rising hope gave Ryan the courage to smile. “Not very sick. Just a little under the weather. You know how it is. She only had the kid about four, five months ago.”

“If I’m not too curious, what is all this? What did this woman say to you? She called this afternoon and I thought she acted a little off her rocker.”

“I might as well tell you, mister,” the trooper said. Ryan moved out onto the porch.

Suddenly the woman darted into the house. Ryan made a grab for her and missed.

One of the troopers grabbed Ryan and the other one went after the woman. The trooper who had taken Stan Ryan’s arm said, “Joe’ll grab her. She’s just a harmless nut, I guess.”

Stan, listening, heard the woman go up the stairs, the trooper pounding behind her. He knew that there wasn’t much time. The woman would be looking for a woman and a baby.

The money was in the kitchen. There was a small chance. He turned half away from the trooper, let his hand drop down until his fingertips touched the cool butt of the gun.

From somewhere upstairs the woman yelled loudly. Stan yanked the gun out, shot twice at the middle of the trooper.

He ignored the clothes, grabbed the brown suitcase. Someone shouted hoarsely. A more authoritative gun roared.

The coupe motor caught the first time, and he was glad that he had backed it into the garage.

It jumped down the drive and a figure ran out from the side of the house, an orange-red jet of flame spurting toward the car. The car swerved, thumping on the rim, wedging against the side of the house.

He ran fifty feet before the slug smashed his shoulder. The impact drove him over onto his face and he rolled, sobbing, yelling with pain and fear and the knowledge that he would die.

Two days later, after Stanley Ryan had dictated his confession to the police stenographer who sat by his hospital bed, he said to the lieutenant, “I’ve been thinking. Why did that Clarey woman bring the troopers around?”

The lieutenant, a weary-looking man in his fifties, inspected the end of his dead cigar and said, “Why, son, she thought you’d gone out of your head and killed your wife and kid.”

Stan puzzled over that. “Why should she think anything like that?”

“She has two little kids of her own, son. She found the weak spot in your window dressing.”

“Weak spot?”

“Sure, Ryan. Weak as hell. You see, you had those things on the line every day, and every day she’d take a look, because she missed the one thing that should have been out there. She missed the one thing real bad. And finally she had to come over to talk to you. If you’d given her a chance, she was going to ask about it. There was one very necessary thing that wasn’t out there every day blowing in the breeze. And young Mrs. Clarey knew there wasn’t any diaper service that far out of town.”

The Night Is Over

(“You’ve Got to Be Cold,” The Shadow , April — May 1947)

There was something infinitely irritating about the puffed, water-wrinkled hands of the man behind the bar. He was wringing out a rag with soft ineffectuality, humming a nasal tune that had been beaten to death by the jukeboxes.

Walker Post stifled the impulse to snarl at him. It was pointless. You can’t climb a man because you don’t like his hands, or you don’t like the tune he hums. He hadn’t been in that particular bar before. A quiet neighborhood spot, drowsing in the heat of an early July afternoon. One other customer, an old man with a ragged yellow beard, sat at a table and sweated in the sun that came in the wide window. Walker Post realized that he was holding himself tense and rigid on the barstool. His shoulder muscles hurt. He made himself slump and forced his eyes away from the bartender’s hands. He swallowed the last inch of rye and water and slid the glass down toward the bartender. He looked across at his own face in the blue-tinted mirror behind the bar. It’s so hard to look at your own face and know what you look like, he thought. What do I see? Dusty hair and pale gray eyes and lips that are thin. Thick shoulders and a sullen look around the mouth and chin. New lines from the corners of my nose to my mouth. The hair has gone back a bit further. A wrinkled and soiled collar. What am I and where am I going and why don’t I give a damn?

There had been people who had given a damn. Four years ago when he had been twenty-seven, when he had married Ruth, she had given a damn. His mother had always cared. Faulkner, the drafting-room chief, had cared, once upon a time.

He realized that going back to work for Faulkner had been a mistake. They had all been so kind and had tried to be so understanding. He shuddered, remembering the soft touches of their hands on his shoulders. It had been so unreal to stand and see the January snow piled so deeply across the trim new graves of Ruth and his mother. He had brushed the snow away so he could read the dates on the stones. Nineteen forty-six. The paper had used the term “common disaster.” Sure. It was a disaster and they seemed to be common enough. He could crawl up seven beaches with his eyes clouded with cold sweat and his fingers slipping on the gun and the grit of fine sand in his teeth, while Ruth skids the car through the side of a bridge.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «More Good Old Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «More Good Old Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «More Good Old Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)