The news was so startling that I hardly knew what to say. Alderman Durham’s EYE team deployed to kill Howard Fepple? That hardly seemed possible. In fact, I didn’t think it could be possible, because the guard at the Hyde Park Bank would have noticed them-you wouldn’t mistake Durham ’s EYE troops for expectant parents going up to a Lamaze class. But it must have been some EYE hangers-on who broke into Amy Blount’s apartment.

I pressed my palms against my eyes, as if that would bring any clarity to my vision. Finally I decided to tell Gertrude Sommers a good deal of the events of the last week and a half, including the old journals that Ulrich Hoffman entered his payments in.

“I don’t understand any of this,” I finished. “But I will have to talk to Alderman Durham. And then-I may have to talk to the police, as well. One man is dead, another critically wounded. I don’t understand what possible connection there is here between these old books of Hoffman’s and the alderman-”

I halted. Except that Rossy had singled out Durham on the street on Tuesday. He was just back from Springfield, where they’d killed the Holocaust Asset Recovery Act, where Ajax had thrown its weight behind Durham ’s slave-reparations rider. And the demonstrations had stopped.

Rossy was from a European insurance company. Carl had thought Ulrich’s records looked similar to the ones a European insurance agent had kept on his father many years ago. Was that what connected Rossy to the Midway Insurance Agency?

I picked up my briefcase and pulled out the photocopies of Ulrich’s journal. Mrs. Sommers watched me, affronted at first by my inattention, then interested in the papers.

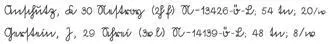

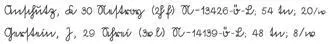

“What is that? It looks like Mr. Hoffman’s handwriting. Is this his record of Mr. Sommers’s insurance?”

“No. But I’m wondering if it’s a record of someone else’s insurance that he sold in Europe sixty-five years ago. Look at this.”

“But it isn’t an E, it’s an N. So it can’t be an Edelweiss policy number. Or it is, but they have their own company code.”

“I suppose you know what you’re talking about, young lady. But it doesn’t mean a thing to me. Not one thing.”

I shook my head. “These numbers don’t mean anything to me. But other things are starting to make a horrible kind of sense.”

Except for what her husband’s insurance policy had to do with all this. I would give a month’s pay, and put icing on it, if I could see what Howard Fepple had found when he looked at Aaron Sommers’s file. But if Ulrich had sold insurance for Edelweiss before the war, if he’d been one of those men coming into the ghetto on his bicycle on Friday afternoons, as Carl had been describing last night-but Edelweiss had been a small regional carrier before the war. So they said. So they said in “One Hundred Fifty Years of Life.”

I got up abruptly. “I will get your nephew Isaiah cleared of all charges against him, one way or another, although exactly how I’ll do that I have to say I honestly don’t know right this minute. As for your nephew Colby-I’m not a fan of housebreaking, or people supplying others with guns for crimes. However, I have a feeling that Colby’s in more danger from his accomplices than he is from the law. I have to go now. If my suspicions are correct, the heart of this mystery is downtown, or maybe in Zurich, not here.”

In my car, I turned my phone back on and called Amy Blount. “I have a different question for you today. The section of your Ajax history where you talked about Edelweiss-where did you get that material?”

“The company gave it to me.”

I made a U-turn, one hand on the wheel, one on the phone. I braked to avoid a cat that suddenly streaked across the road. A little girl followed, screaming its name. The car fishtailed. I dropped the phone and pulled over to the curb, my heart pounding. I had been lucky not to hit the girl.

“Sorry-I’m demented right now, trying to do too many things at once, and driving stupidly,” I said when I’d recovered enough to reestablish the connection. “Were these archival records? Financials, anything like that?”

“A summary of financials. All they wanted on Edelweiss was that little bit at the end. The book is really about Ajax, so I didn’t see the need to look at Edelweiss archives.” She was defensive.

“What was in the summary?”

“High-level numbers. Assets and reserves, principal offices. Year-by-year, though. I don’t remember the details. I suppose I could ask the Ajax librarian.”

A couple of men came out of a derelict courtyard. They looked at the Mustang and then at me and gave a thumbs-up gesture for both of us. I smiled and waved.

“I need a way to find out if they had an office in Vienna before the war.” Edelweiss’s numbers didn’t matter, come to think of it: maybe they really had been a small regional player in the thirties. But they could still have been selling insurance to people who were obliterated in the war’s blistering furnaces.

“The Illinois Insurance Institute has a library which might have something that would help you,” Amy Blount suggested. “I used it when I was doing research for the Ajax book. They have a strange hodgepodge of old insurance documents. They’re in the Insurance Exchange building, you know, on West Jackson.”

I thanked her and hung up. My phone rang as I was negotiating the merge onto the Ryan at Eighty-seventh, but nearly hitting that child a few minutes ago made me keep my attention on the road. Although I couldn’t stop speculating about Edelweiss. They bought Ajax, a coup, acquiring America ’s fourth-largest property-casualty insurer at fire-sale prices. And then found themselves facing legislation demanding recovery of Holocaust-era assets, including life-insurance policies. Their investment could have turned from gold mine to bankruptcy court if they had a huge arrears of unpaid life-insurance claims all coming due at once.

Swiss banks were fighting tooth and claw to keep heirs of Holocaust victims from claiming assets deposited in the frantic years before the war. European insurers were stonewalling just as hard. It must be relatively rare for children to know their parents had insurance. Even if others, like Carl, had been sent downstairs with money to pay the agent, I was betting he was unusual in knowing what company held his father’s policy. When my father died, it was only on going through his papers that I found his life insurance.

When not only your family, but your house, maybe even your entire town, has been obliterated-you’d have no records to turn to. And if you did, the company would treat you the way it had Carl: denying the claim because you couldn’t present a death certificate. They really were a prize group of bastards, those banks and insurers.

My phone rang again, but I picked it up only to switch it off. If those books of Hoffman’s contained a list of life-insurance policies bought by people like Carl’s father or Max’s, people who died in Treblinka or Auschwitz, it wasn’t such a large list that Edelweiss would lose much from paying the claims. All it would do is give several hundred people the knowledge that their parents or grandparents had bought policies and give them the policy numbers. It wasn’t as if there’d be a stampede on Edelweiss assets.

Unless, of course, states began passing Holocaust Asset Recovery Acts, such as the one Ajax torpedoed last week. The company would have had to make an audited search of its policy files-of all the hundred or so companies that made up the Ajax group, now including Edelweiss-and prove that it wasn’t sitting on policies belonging to the dead of the war in Europe. That might have cost them a bundle.

Читать дальше