Wrapped in a terry cloth robe, I returned to the living room: I’d dropped the accordion file on the piano bench when I’d run into the apartment. For a long moment I stared down at Ulrich’s disfigured face, which looked even worse for the blood that had seeped onto it.

I’d been wanting to see these papers since Paul showed up at Max’s last Sunday. Now that they were within my reach I almost couldn’t bear to read them. They were like the special present of my childhood birthdays-sometimes wonderful, like the year I got roller skates, sometimes a disappointment, like the year I longed for a bicycle and got a concert dress. I didn’t think I could bear to open the file and find, well, another concert dress.

I finally undid the black ribbon. Two leather-bound books fell out. On the front of each was stamped in peeling gold letters Ulrich Hoffman. So that was why Rhea Wiell had smirked at me: Ulrich was his first name. I could have called every Ulrich who’d ever lived in Chicago and never found Paul’s father.

A black ribbon hung from the middle of one of the books. I set the other down and opened this one to its marker. The paper, and the ornate script on it, looked much the same as the fragment I’d found in Howard Fepple’s office. A person who was fond of himself, that was what the woman at Cheviot Labs had said, using expensive paper for keeping accounting notes. A domestic bully, king only of the tiny empire of his son? Or an SS man in hiding?

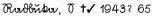

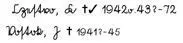

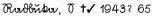

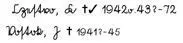

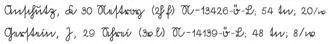

The page I was looking at held a list of names, at least twenty, maybe thirty. Even in the difficult script, one name in particular halfway down the page caught my eye:

Next to it, in a hand so heavy it cut through the paper, Paul had written in red, Sofie Radbuka. My mother, weeping for me, dying for me, in heaven all these years praying for me.

My skin crawled. I could hardly bear to look at the page. I had to treat it as a problem, a conundrum, like the time in the PD when I’d represented a man who had skinned his own daughter. His day in court where I did my best, my God, because I’d managed to dissociate myself and treat it as a problem.

All the entries followed the same format: a year with a question mark, and then a number. The only variation I saw was that some had a cross followed by a check mark, others just a cross.

Did this mean they had died in 1943, or ’41? With 72 or 45 something.

I opened the second book. This one held similar information to the scrap I’d found in Fepple’s office, columns of dates, all written European style, most filled in with check marks, while some were blank. What had Howard Fepple been doing with a piece of Ulrich Hoffman’s old Swiss paper?

I sat down hard on the piano bench. Ulrich Hoffman. Rick Hoffman. Was that Paul Radbuka’s father? The old agent from Midway with his Mercedes, and the books he carried around with him to check off who paid him? Whose son had an expensive education, but never amounted to anything? But-had he sold insurance in Germany as well? The man who’d owned these books was an immigrant.

I dug Rhonda Fepple’s number out of my briefcase. Her phone rang six times before the answering machine picked up, with Howard Fepple’s voice eerily asking for me to leave a message. I reminded Rhonda that I was the detective who had been to her house on Monday. I asked her to call me as soon as possible, giving her my cell-phone number, then went back to stare at the books again. If Rick Hoffman and Ulrich were the same man, what did these books have to do with insurance? I tried to match the entries with what I knew of insurance policies, but couldn’t make sense of them. The front of the first book was filled with a long list of names, with a lot of other data that I couldn’t decipher.

The list went on for pages. I shook my head over it. I squinted at the difficult ornate writing, trying to interpret it. What about it had made Paul decide Ulrich was with the Einsatzgruppen? What was it about the name Radbuka that had persuaded him it was his? The papers were in code, he’d screamed at me outside the hospital yesterday-if I believed in Rhea I’d understand it. What had she seen when he’d shown these pages to her?

And finally, who was the Ilse Bullfin who had shot him? Was she a figment of his imagination? Had it been a garden-variety housebreaker whom he thought was the SS? Or was it someone who wanted these journals? Or was there something else in the house that the person had taken as she-he-whoever-tossed all those papers around.

Even laying out these questions on a legal pad at my dining room table didn’t help, although it did make me able to look at the material more calmly. I finally put the journals to one side to see if there was anything else in the file. An envelope held Ulrich’s INS documents, starting with his landing permit on June 17, 1947, in Baltimore, with son Paul Hoffman, born March 29, 1941, Vienna. Paul had X’d this out, saying, Paul Radbuka, whom he stole from England. The documents included the name of the Dutch ship they had arrived on, a certification that Ulrich was not a Nazi, Ulrich’s resident-alien permits, renewed at regular intervals, his citizenship papers, granted in 1971. On these, Paul had smeared, Nazi War Criminal: revoke and deport for crimes against humanity. Paul had said on television that Ulrich wanted a Jewish child to help him get into the States, but there wasn’t any reference to Paul’s religion, or to Ulrich’s, in the landing documents.

My brain would work better if I got some rest. It had been a long day, what with finding Paul’s body and his unnerving refuge. I thought of him again as a small child, locked in the closet, terrified, his revenge now as puny as when he’d been a child.

I slept heavily, but unpleasantly, tormented by dreams of being locked in that little closet with swastikaed faces leering down at me, with Paul dancing dementedly outside the door like Rumpelstiltskin, crying, “You’ll never know my name.” It was a relief when my answering service brought me back to life at five: a woman named Amy Blount had called. She said she had offered to look at a document for me and could stop by my office in half an hour or so if that was convenient.

I really wanted to get up to Max’s. On the other hand, Mary Louise would have left a report on her day’s interviews with Isaiah Sommers’s friends and neighbors. Come to think of it, Ulrich Hoffman’s books might mean something to Amy Blount: after all, she was a historian. She understood odd documents.

I put Ninshubur in the dryer and called Ms. Blount to say I was on my way to my office. When I got there, I made copies of some of the pages in Ulrich’s books, including the one with Paul’s heavy marginalia.

While I waited for Ms. Blount, I looked over Mary Louise’s neatly typed report. She had drawn a succession of blanks on the South Side. None of Isaiah Sommers’s friends or coworkers could think of anyone with a big enough grudge against him to finger him to the cops.

His wife is an angry woman, but at the bottom I believe she is on his side-I don’t think she set him up. Terry Finchley tells me the police right now have two competing theories:

1. Connie Ingram did it because Fepple tried to assault her. They don’t like this because they believe what she says about not going to his office. They do like it because her only alibi is her mother, who sits in front of the tube most nights. They also can’t get around the forensic evidence showing that Fepple (or someone) entered his “hot” date in his computer on Thursday, when everyone agrees Fepple was still alive.

Читать дальше