But Spott deserved his punishment. He’d committed a crime familiar to every member of every police force in the world: Contempt of Cop. You didn’t run from cops, you didn’t disrespect them with your big mouth, and you never, under any circumstances, hit them. If you did, you paid a price.

That was it, though, the full extent as far as Lodge was concerned. To the best of his knowledge, he’d never beaten a prisoner with any weapon but his hands. Never.

“What if I’m innocent?” he finally asks his lawyer.

“What if there’s a million black people residing in Brooklyn who already think you’re guilty?”

One week later, suspended Police Officer David Lodge appears before Justice Harold Roth in Part 70 of the Criminal Term of Brooklyn Supreme Court. Lodge is the last piece of business on Roth’s calendar late this Friday afternoon. It’s a cameo shot, posed in front of the raised dais where Roth sits — Lodge, his lawyer Savio, and the deputy chief of the District Attorney’s Homicide Bureau — nobody is in the audience in the cavernous courtroom.

Justice Roth is not one to smile unduly or waste words. “Well, counsellor?”

“Yes, your honor,” Savio marshalls his words. “My client has authorized me to withdraw his previously entered plea of not guilty and now offers to plead guilty to manslaughter in the first degree, a class-C violent felony, under the first count of the indictment, in satisfaction of the entire indictment.” Savio stops then, but does not look at Lodge, who is three feet to his right, standing ram-rod straight, staring fixedly at the judge. Lodge heard not a word Savio said.

“Is that what you want to do, Mr. Lodge?” Roth asks, not unkindly.

Mister Lodge. The words rock him like a blow to the body. Yet he remains transfixed, mute.

A full minute has passed. Roth has had enough. “Come up.”

The lawyers hasten up to the bench, huddling with Roth at the sidebar. Savio earnestly explains that his client is unable to admit guilt because he was in the throes of an alcoholic blackout when he allegedly bludgeoned the victim, and so has no memory of the event. After several minutes of back-and-forth, Roth ends the debate.

“He can have an Alford-Serrano. Step back.”

At Lodge’s side, Savio explains their good fortune. In an Alford-Serrano plea — normally reserved for the insane — Roth will simply ask Lodge if he is pleading guilty because Lodge believes that the evidence is such that he will be found guilty at trial. Savio whispers urgently in Lodge’s ear, an Iago to his Othello.

Suddenly, David Lodge’s body goes slack, his gaze falters. Lodge has an epiphany. He sees the faces of all the skells he’d ever arrested who’d whined innocent, and for the only time in his life he’s flooded with a compassion, till the fear takes hold — the fear of a small child upon awaking alone in the dark in an empty house.

Part IV

Backwater Brooklyn

Triple Harrison

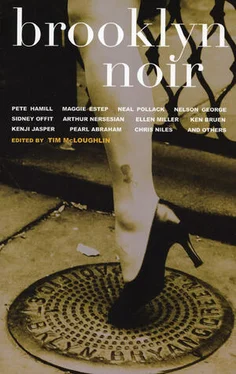

by Maggie Estep

East New York

She was wearing her t-shirt but she’d shed her jeans and her bleach-stained panties. She had me pinned down by the shoulders and her long dirty hair was tickling my cheeks as she hovered over me. I kept trying to look into her eyes but she had her face turned away. Even though her body was doing things to mine, she didn’t want me seeing what her eyes thought about it.

“Stella.” I said her name but she wouldn’t look at me. She took one hand off my shoulder and started raking her fingernails down my chest a little too violently.

“Hey, that hurts, girl,” I warned, trying to grab at her hand.

“What?” she asked.

“You’re hurting me,” I repeated.

Her eyes suddenly got smaller, her mouth shrank like a flower losing life, and she slapped me.

“Hey! Shit, stop that, Stella,” I protested, shocked. I didn’t know much about the girl but what I’d seen had been distinctly reserved and nonviolent.

“What’s the matter?” I asked her.

She slapped me again. I tried to grab her hands but she made fists and pummeled my chest.

“You fuck!” she screamed.

I was pretty baffled. I’d been seeing Stella for a couple of months. She never said much, but up until now, she’d seemed to like me just fine. She would turn up on my door-step late at night, peel off her clothes, and get in my bed. I’d bought her flowers once and taken her out to dinner twice. I’d never said anything but nice things to her and I didn’t think I’d done anything to incur her fists.

“What’s the matter, Stella?” I asked again, finally getting hold of her wrists and flipping her under me.

“Get offa me, Triple,” she spat, wiggling like an electrified snake.

I released her wrists and slid my body off hers. I lay there, panting a little from the effort of the struggle.

I watched Stella scramble to her feet, then pick her panties and jeans off the floor. She yanked her clothes on. She was so angry she put her pants on backwards.

“I don’t get it, what’d I do, Stella?” I asked her, as she furiously took her pants back off then put them on the right way. She ignored me.

I was really starting to like Stella. Maybe that’s what got her mad.

She zipped her pants, slipped her feet into her cheap sneakers, then went to the door and walked out, slamming it behind her.

“What the fuck?” I said aloud. There was no one to hear me though. My dog had died of old age and the stray cat I’d taken in had gotten tired of me and moved on. It was just me and the peeling walls of the tiny wood-frame house. And all of a sudden that didn’t feel like much at all.

Ever since Stella had come along, I hadn’t dwelled on any of it. On being broke and close to forty and living in a condemned house that was so far gone no one bothered to come kick me out of it. But now, for mysterious reasons, Stella probably wouldn’t be back and there wasn’t much to distract me from my condition. I only had one thing left that gave me any hope, and that was my horse. As it happened, it was just about time to go feed her, so I put on my clothes and went out, heading for the barn a hundred yards down from the house. I don’t suppose too many Brooklynites have horses, period, never mind keep them a hundred yards from the house. But real estate isn’t exactly at a premium here at the ass-end of Dumont Avenue, where Brooklyn meets up with the edge of Queens.

It was close to dawn now and the newborn sun was throwing itself over the bumpy road. Two dogs were lying on a heap of garbage ten yards down from my house. One of them, some kind of shepherd mix, looked up at me. He showed a few teeth but left it at that.

Our little neighborhood is technically called Lindenwood but most people call it The Hole. A canyon in a cul-de-sac at the edge of East New York. It had been farmland in the not-so-distant past, then, as projects sprung up around it, it became a dumping ground. A few old-timers held on, maintaining their little frame houses, keeping chickens and goats in their yards. I don’t know who the first person to keep a horse here was, but it caught on. Within five years, about a dozen different ramshackle stables were built using old truck trailers and garden sheds. Each stable had its own little yard, some with paddocks in the back, all of it spread over less than five acres. Now, about forty horses live in The Hole, including my mare, Kiss the Culprit. I brought her here six months ago. It’s not exactly pastoral but we make due.

I reached the big steel gate enclosing the stable yard, unlocked it, and pushed it open. The little area looked like it usually did. A patch of dirt with a few nubs of grass fighting for life in front of the green truck trailer that had been converted to horse stalls. Beth, the goat, butted me with her head. The six horses started kicking at their stall doors, clamoring for breakfast, their ruckus waking up the horses in the surrounding barns so that, within a few minutes, the entire area was sounding like a bucolic barnyard in rural Maryland and, in spite of my troubles, I suddenly felt good all over. Particularly as I took my first look of the day at Kiss the Culprit. She had her head hanging over her stall door and was looking at me expectantly. She looked especially good that morning in spite of the fact that, by most standards, she’s not considered a perfect specimen of the Thoroughbred breed. She’s small with an upside-down neck and a head too big for the rest of her. She’s slightly pigeon-toed and, back in her racing days, she’d run with a funny gait that only I thought resembled the great Seabiscuit’s.

Читать дальше