Fräulein Krömeier brought me more post from the office. She too had been called on the telephone several times, mostly by individuals from the same parties or groupings, but new were the communications from diverse communist organisations. It has now slipped my mind why they got in touch, but I do not suppose the reason was much different from Stalin’s in 1939, when he concluded our non-aggression pact. What united these callers and scribes was that they were all soliciting my membership of their respective associations. Only two parties, in fact, failed to contact me. Simpletons would probably put this down to indifference, but I knew better. Which is why, when an unknown Berlin number flashed on my telephone the following day, I hollered speculatively, “Hello? Is that the S.P.D.?”

“Er, yes… Am I speaking to Herr Hitler?” a voice at the other end of the line said.

“Indeed you are,” I said. “I’ve been waiting for you to call!”

“For me?”

“Not specifically. But for someone from the S.P.D. Who’s speaking, please?”

“Gabriel, Sigmar Gabriel. It’s fantastic that you can speak on the phone again. I’d heard and read the most awful things. You sound back on form.”

“That’s purely on account of your telephone call.”

“Really? Are you that pleased I phoned?”

“No, not as such. I’m pleased because it took you so long. In the time it takes for German Social Democracy to conceive of an idea one could cure two severe cases of tuberculosis.”

“Hahaha,” Gabriel sniggered, and it sounded exceedingly natural. “You’re right, sometimes that’s certainly the case. Look, this is exactly why I’m calling…”

“I know! Because my own party is in hibernation at present.”

“What party?”

“You disappoint me, Gabriel! What is the name of my party?”

“Erm…”

“Go on!”

“Excuse me? I’m not exactly sure what you’re…”

“N.… S.… D.… A.…?”

“P.?”

“Precisely. P. It’s having a rest at the moment. And you would like to know whether I might just be looking for a new home. In your party!”

“Well, I was actually…”

“By all means send your forms to my office,” I said chattily.

“Listen, have you just taken some painkillers? Or a few too many sleeping tablets?”

“No,” I said, and was about to add that I wouldn’t need any after this conversation. Then it occurred to me that Gabriel might be right. One never really knows what on earth doctors and nurses administer via those bags with tubes. And it also struck me that in its present form, this S.P.D. was no longer a party to be rounded up and incarcerated in a concentration camp. Its sluggishness might even render it useful in some matters. I therefore made immediate reference to some of medicines I was taking and took my leave very cordially.

I leaned back on my pillow, wondering who might be the next person to call. In fact all that I was missing was a telephone conversation with someone from the chancellor’s electoral union. Who might that be? The lumpy matron herself was out of the question, of course. But I wouldn’t have minded speaking to the employment minister. I was dying to know why she had stopped procreating only one child away from receiving the Gold Mothers’ Cross. That Guttenberg would have been interesting too. Even though he had emerged from a centuries-deep swamp of aristocratic incest, here was a man who had the capacity to think in a wider context, without allowing professorial objections endlessly to get in the way. But his political heyday seemed now to be past. Who else? The ecological fellow with the spectacles? The drip of a whip? The wheelchair-bound aspiring-conservative Swabian in charge of finances?

And there were the Valkyries, scouring the battlefields for fallen heroes once more. The number was unfamiliar to me, but the area code was Berlin. I concluded it must be the windbag.

“Good day, Herr Pofalla,” I said.

“I’m sorry?” This was indisputably the voice of a woman. I put her as a bit older, maybe mid-fifties.

“I do beg your pardon — who is speaking?”

“My name is Golz, Beate Golz,” and she uttered the name of a well-known German-sounding publishing house. “And to whom am I speaking?”

“Hitler,” I said, clearing my throat. “I’m terribly sorry, I was expecting somebody else.”

“Is this a bad time? Your office said it would be fine for me to phone in the…”

“No, no,” I said. “It’s perfectly alright. But kindly, put no more questions about how I’m feeling.”

“Is it that bad?”

“No, but I’m beginning to sound like an old gramophone record.”

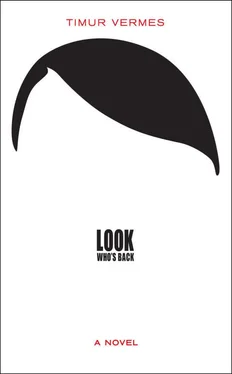

“Herr Hitler… I’m calling to ask whether you’d like to write a book?”

“I already have,” I said. “Two, in fact.”

“I know. More than ten million copies. We’re very impressed. But someone with your potential ought not to leave a gap of eighty years.”

“Well, look, that gap was not entirely within my control…”

“You’re absolutely right. I can well understand that writing doesn’t come so easily when the Russians are rolling over your bunker…”

“Indeed,” I said. I could barely have put it better myself. I was pleasantly surprised by Frau Golz’s ability to empathise.

“But now the Russians are no longer here. And however much we enjoy your weekly round-up on the telly, I think it’s time the Führer produced another report on his view of the world. Or — before I make a total fool of myself here — do you already have other contractual commitments?”

“No, I’m usually published by Franz Eher,” I said, but then realised that by now he must be in retirement too.

“I’m assuming you haven’t heard from your publisher in a while?”

“In point of fact, you’re right,” I mused. “I wonder who’s cashing in my royalties at this moment?”

“The state of Bavaria, if I’m rightly informed,” Frau Golz said.

“What impertinence!”

“You could sue, of course, but you know what the courts are like…”

“You’re telling me!”

“I’d be delighted, however, if you took the somewhat simpler route instead.”

“Which would be…?”

“You write a new book. In a new world. We’d be happy to publish it. And as we’re all professionals here I can offer you the following.” Then she set forth a schedule of major marketing strategies and mentioned a sum as an advance payment, which even in this suspect euro money elicited my approval — though of course I kept this to myself for the time being. I would also be allowed to choose my own colleagues, whose remuneration would likewise be covered by the publishing house.

“Our one condition: it must be the truth.”

I rolled my eyes. “I suppose you’ll be wanting to know what my real name is.”

“No, no, no. Your name is Adolf Hitler, of course. What other name would we put on the book? Moses Halbgewachs?”

I laughed. “Or Schmul Rosenzweig. I like you.”

“What I’m trying to say is that we’re not after a humorous book. I assume you’d be thinking along the same lines. The Führer doesn’t make jokes.”

It was astonishing how simple everything was with this woman. She knew exactly what she was talking about. And with whom.

“Will you have a think about it?”

“Give me a little time,” I said. “I will be in touch.”

I waited for five minutes, precisely. Then I called her back. I demanded a substantially higher sum. In retrospect I have to presume that she was expecting this.

“O.K. then: Sieg Heil!” she said.

“May I take that as a deal?” I asked.

“You may,” she laughed.

“Then a deal it is!”

Читать дальше