Sabine Baring-Gould - Curiosities of Olden Times

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sabine Baring-Gould - Curiosities of Olden Times» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Curiosities of Olden Times

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41546

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Curiosities of Olden Times: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Curiosities of Olden Times»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Curiosities of Olden Times — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Curiosities of Olden Times», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A sufficiency of historical notes. I will proceed at once – perhaps somewhat strangely – to give the reader a specimen of a will coming decidedly under the heading of this article. It is that of a Pig . The will is ancient enough. S. Jerome, in his “Proœmium on Isaiah,” speaks of it, saying, that in his time (fourth century) children were wont to sing it at school, amidst shouts of laughter. Alexander Brassicanus, who died in 1539, was the first to publish it; he found it in a MS. at Mayence. Later, G. Fabricius gave a corrected edition of it from another MS. found at Memel, and, since then, it has been in the hands of the learned. The original is in Latin; I translate, modifying slightly one expression and omitting one bequest:

I, M. Grunnius Corocotta Porcellus, have made my testament, which, as I can’t write myself, I have dictated.

Says Magirus, the cook: “Come along, thou who turnest the house topsy-turvy, spoiler of the pavement, O fugitive Porcellus! I am resolved to slaughter thee to-day.”

Says Corocotta Porcellus: “If ever I have done thee any wrong, if I have sinned in any way, if I have smashed any wee pots with my feet; O Master Cook, grant pardon to thy suppliant!”

Says the cook Magirus: “Halloo, boy! go, bring me a carving-knife out of the kitchen, that I may make a bloody Porcellus of him.”

Porcellus is caught by the servants, and brought out to execution on the xvi. before the Lucernine Kalends, just when young colewortsprouts are in plenty, Clybaratus and Piperatus being Consuls.

Now when he saw that he was about to die, he begged hard of the cook an hour’s grace, just to write his will. He called together his relations, that he might leave to them some of his victuals; and he said:

I will and bequeath to my papa, Verrinus Lardinus, 30 bush. of acorns.

I will and bequeath to my mamma, Veturina Scrofa, 40 bush. of Laconian corn.

I will and bequeath to my sister, Quirona, at whose nuptials I may not be present, 30 bush. of barley.

Of my mortal remains, I will and bequeath my bristles to the cobblers, my teeth to squabblers, my ears to the deaf, my tongue to lawyers and chatterboxes, my entrails to tripemen, my hams to gluttons, my stomach to little boys, my tail to little girls, my muscles to effeminate parties, my heels to runners and hunters, my claws to thieves; and, to a certain cook, whom I won’t mention by name, I bequeath the cord and stick which I brought with me from my oak-grove to the sty, in hopes that he may take the cord and hang himself with it.

I will that a monument be erected to me, inscribed with this, in golden letters:

M. Grunnius Corocotta Porcellus, who lived 999 years, – six months more, and he would have been 1000 years old.

Friends dear to me whilst I lived, I pray you to have a kindness towards my body, and embalm it well with good condiments, such as almonds, pepper, and honey, that my name may be named through ages to come.

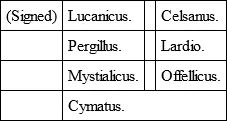

O my masters and my comrades, who have assisted at the drawing up of this testament, order it to be signed.

Whilst on this subject we might say a word about the epitaph on the mule of P. Crassus; or about that written by Rapin on the ass, which, poor fellow, was eaten whilst in the flower of his age, during the siege of Paris, in 1590; or about Joachim du Bellay, who composed an epitaph on his cat; or about Justus Lipsius, who erected mausoleums for his three cats – Mopsus, Saphisus, and Mopsulus; but we are not writing on epitaphs or gravestones.

We proceed to give a few instances of animals which have received legacies.

If it is a keen trial for a husband to leave his wife, for a young man to be taken from his pleasures, or a commercial man from his business, can we wonder at old ladies feeling the wrench sharp which tears them from the society of their dear cats – the companions of their spinsterhood or widowhood; or at old bachelors being distressed at having to part with their faithful dogs? – to part with them for ever, too, unless we believe in the suggestion of Bishop Butler and Theodore Parker, that there is a future for beasts, and enjoy the confidence of Mr. Sewell of Exeter College, who dedicated one of his published poems “To my Pony in Heaven.”

The Count de la Mirandole, who died in 1825, left a legacy to his favourite carp, which he had nourished for twenty years in an antique fountain standing in his hall. In low life we find the same love for an animal displayed by a peasant of Toulouse, in 1781, who doted on his old chestnut horse, and left the following will:

I declare that I institute my chestnut horse sole legatee, and I wish him to belong to my nephew N.

This testament was attacked, but, curiously enough, it received legal confirmation.

The following clause from a will was in the English papers for March 1828:

I leave to my monkey, my dear, amusing Jackoo, the sum of 10 l. sterling, to be enjoyed by him during his life; it is to be expended solely in his keep. I leave to my faithful dog, Shock, and to my beloved cat, Tib, 5 l. sterling a-piece, as yearly pension. In the event of the death of one of the aforesaid legatees, the sum due to him shall pass to the two survivors, and on the death of one of these two, to the last, be he who he may. After the decease of all parties, the sum left them shall belong to my daughter G – , to whom I show this preference, above all my children, because she has a large family and finds a difficulty in filling their mouths and educating them.

But a more curious case still is that of Mr. Berkley of Knightsbridge, who died 5th May 1805. He left a pension of £25 per annum to his four dogs. This singular individual had spent the latter part of his life wrapped in the society of his curs, on whom he lavished every mark of affection. When any one ventured to remonstrate with him for expending so much money on their maintenance, or suggested that the poor were more deserving of sympathy than those mongrel pups, he would reply: “Men assailed my life: dogs preserved it.” This was a fact, for Mr. B. had been attacked by brigands in Italy, and had been rescued by his dog, whose descendants the four pets were. When he felt his end approaching, he had his four dogs placed on couches by the sides of his bed. He received their last caresses, extended to them his faltering hand, and breathed his last between their paws. According to his desire, the busts of these favoured brutes were sculptured at the corners of his tomb.

In 1677, died Madame Dupuis, who, under her maiden name of Mademoiselle Jeanne Felix, had been known as a great musician. Her will was so extraordinary and malicious that it was nullified. To it was attached a memorandum, which is still more extraordinary. We shall not quote the passages wherein she vilifies her son-in-law, imputing to him every vice she can think of, but translate the final clause:

I pray Mademoiselle Bluteau, my sister, and Madame Calogne, my niece, to take care of my cats. Whilst these two live, they shall have thirty sous a month, that they may be well fed. They must have, twice a day, meat soup of the quality usually served on table; but they must be given it separately, each having his own saucer. The bread must not be crumbled in the soup, but cut up into pieces about the size of hazel-nuts, or they cannot eat it. When boiled beef is put into the pot with the soaked bread, some thin slices of raw meat must be put in as well, and the whole stewed till it is fit for eating. When only one cat lives, half the money will suffice. Nicole Pigeon shall take care of the cats, and cherish them. Madame Calogne may go and see them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Curiosities of Olden Times»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Curiosities of Olden Times» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Curiosities of Olden Times» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.