Sabine Baring-Gould - Curiosities of Olden Times

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sabine Baring-Gould - Curiosities of Olden Times» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Curiosities of Olden Times

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41546

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Curiosities of Olden Times: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Curiosities of Olden Times»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Curiosities of Olden Times — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Curiosities of Olden Times», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In this case no cypher was employed; we shall come, now, to the use of cyphers.

When a despatch or communication runs great risk of falling into the hands of an enemy, it is necessary that its contents should be so veiled, that the possession of the document may afford him no information whatever. Julius Cæsar and Augustus used cyphers, but they were of the utmost simplicity, as they consisted merely in placing D in the place of A; E in that of B, and so on; or else in writing B for A, C for B, etc.

Secret characters were used at the Council of Nicæa; and Rabanus Maurus, Abbot of Fulda and Archbishop of Mayence in the ninth century, has left us an example of two cyphers, the key to which was discovered by the Benedictines. It is only a wonder that any one could have failed to unravel them at the first glance. This is a specimen of the first:

The secret of this is that the vowels have been suppressed and their places filled by dots, – one for i, two for a, three for e, four for o, and five for u. In the second example, the same sentence would run – Knckpkt vfrsxs Bpnkfbckk, etc., the vowel-places being filled by the consonants – b, f, k, p, x. By changing every letter in the alphabet, we make a vast improvement on this last; thus, for instance, supplying the place of a with z, b with x, c with v, and so on. This is the system employed by an advertiser in a provincial paper which I took up the other day in the waiting-room of a station, where it had been left by a farmer. As I had some minutes to spare, before the train was due, I spent them in deciphering the following:

and in ten minutes I read: “If William can call or write, Mary will be glad.”

A correspondence was carried on in the Times during May 1862 in cypher. I give it along with the explanation.

Wws. – Zy Efpdolj T dpye l wpeepc ez mjcyp qzc jzf – xlj T daply qfwwj zy lww xleepcd le esp tyepcgtph? Te xlj oz rzzo. Ecfde ez xj wzgp – T lx xtdpclmwp. Hspy xlj T rz ez Nlyepcmfcj tq zywj ez wzzv le jzf. – May 8.

This means – “On Tuesday I sent a letter to Byrne for you. May I speak fully on all matters at the interview? It may do good. Trust to my love. I am miserable. When may I go to Canterbury if only to look at you?”

A couple of days later Byrne advertises, slightly varying the cypher:

Wws. – Sxhrdktg hdbtewxcv “Tmwxqxixdc axzt” udg pcdewtg psktgexhtbtce … QNGCT. “Discover something Exhibition-like for another advertisement. Byrne.”

This gentleman is rather mysterious: I must leave my readers to conjecture what he means by “Exhibition-like.” On Wednesday came two advertisements, one from the lady – one from the lover. WWS. herself seems rather sensible —

Tydeplo zq rztyr ez nlyepcmfcj, T estyv jzf slo xfns mpeepc delj le szxp lyo xtyo jzfc mfdtypdd. – WWS., May 10.

“Instead of going to Canterbury, I think you had much better stay at home and mind your business.”

Excellent advice; but how far likely to be taken by the eager wooer, who advertises thus? —

Wws. – Fyetw jzfc qlespc lydhpcd T hzye ldv jzf ez aczgp jzf wzgp xp. Efpdol ytrse le zyp znwznv slgp I dectyr qczx esp htyozh qzc wpeepcd. Tq jzt lcp yze lmwp le zyp T htww hlte. Rzo nzxqzce jzf xj olcwtyr htqp.

“Until your father answers I won’t ask you to prove you love me. Tuesday night at one o’clock have a string from the window for letters. If you are not able at one I will wait. God comfort you, my darling wife.”

Only a very simple Romeo and Juliet could expect to secure secrecy by so slight a displacement of the alphabet.

When the Chevalier de Rohan was in the Bastille, his friends wanted to convey to him the intelligence that his accomplice was dead without having confessed. They did so by passing the following words into his dungeon, written on a shirt: “Mg dulhxcclgu ghj yxuj; lm ct ulgc alj.” In vain did he puzzle over the cypher, to which he had not the clue. It was too short: for the shorter a cypher letter, the more difficult it is to make out. The light faded, and he tossed on his hard bed, sleeplessly revolving the mystic letters in his brain, but he could make nothing out of them. Day dawned, and, with its first gleam, he was poring over them: still in vain. He pleaded guilty, for he could not decipher “Le prisonnier est mort; il n’a rien dit .”

Another method of veiling a communication is that of employing numbers or arbitrary signs in the place of letters, and this admits of many refinements. Here is an example to test the reader’s sagacity:

I just give the hint that it is a proverb.

The following is much more ingenious, and difficult of detection.

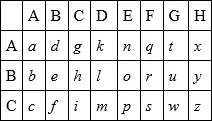

Now suppose that I want to write England ; I look among the small letters in the foregoing table for e , and find that it is in a horizontal line with B, and vertical line with B, so I write down B B; n is in line with A and E, so I put AE; continue this, and England will be represented by Bbaeacbdaaaeab . Two letters to represent one is not over-tedious: but the scheme devised by Lord Bacon is clumsy enough. He represented every letter by permutations of a and b ; for instance,

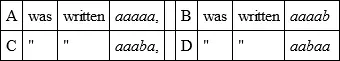

and so through the alphabet. Paris would thus be transformed into abbba, aaaaa, baaaa, abaaa, baaab . Conceive the labour of composing a whole despatch like this, and the great likelihood of making blunders in writing it!

A much simpler method is the following. The sender and receiver of the communication must be agreed upon a certain book of a specified edition. The despatch begins with a number; this indicates the page to which the reader is to turn. He must then count the letters from the top of the page, and give them their value numerically according to the order in which they come; omitting those which are repeated. By these numbers he reads his despatch. As an example, let us take the beginning of this article: then, I = 1, n = 2, w = 3, h = 4, e = 5, m = 6, d = 7, l = 8, o = 9, u = 10, v = 11, omitting to count the letters which are repeated. In the middle of the communication the page may be varied, and consequently the numerical significance of each letter altered. Even this could be read with a little trouble; and the word “impossible” can hardly be said to apply to the deciphering of cryptographs.

A curious instance of this occurred at the close of the sixteenth century, when the Spaniards were endeavouring to establish relations between the scattered branches of their vast monarchy, which at that period embraced a large portion of Italy, the Low Countries, the Philippines, and enormous districts in the New World. They accordingly invented a cypher, which they varied from time to time, in order to disconcert those who might attempt to pry into the mysteries of their correspondence. The cypher, composed of fifty signs, was of great value to them through all the troubles of the “Ligue,” and the wars then desolating Europe. Some of their despatches having been intercepted, Henry IV. handed them over to a clever mathematician, Viete, with the request that he would find the clue. He did so, and was able also to follow it as it varied, and France profited for two years by his discovery. The court of Spain, disconcerted at this, accused Viete before the Roman court as a sorcerer and in league with the devil. This proceeding only gave rise to laughter and ridicule.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Curiosities of Olden Times»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Curiosities of Olden Times» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Curiosities of Olden Times» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.