Walter Besant - South London

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Walter Besant - South London» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:South London

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

South London: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «South London»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

South London — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «South London», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The end of Swegen, as everybody knows, was that St. Edmund of Bury killed him for doubting his saintliness.

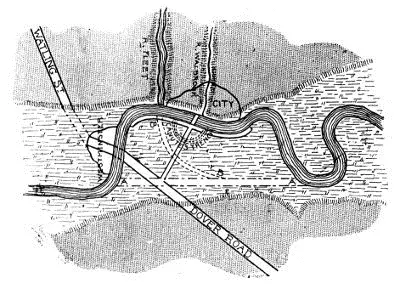

SKETCH MAP

We now come to the three successive sieges by King Cnut. The expedition with which he proposed to reduce London was far finer and more powerful than that of Olaf and Swegen. The poetic description of it says that the ships were counted by hundreds; that they were manned by an army among whom there was never a slave, or a freeman son of a slave, or one unworthy man, or an old man. Freeman asks what nobility meant if all were nobles? A strange question for one so learned! The nobles of Denmark were simply the conquering race; nobility consisted in free birth, and in descent from the conquering race, not the conquered: it was not necessarily a small caste; it might possibly include the larger part of the people.

Cnut anchored off Greenwich and prepared for his siege. First of all, he resolved that the Bridge should no longer bar the way. He therefore cut a trench round the south of the Bridge, by means of which he drew some of his ships to the other side of it. He then cut another trench round the whole of the wall. In this way he hoped to shut in the City and cut off all supplies: if he could not take the place by storm, he would starve it out. There are no details of the siege, but as Cnut speedily abandoned the hope of success and marched off to look after Edmund, his investment of the City was certainly not a success.

He met Edmund and fought two battles with him; with what result history has made us acquainted. He then returned and resumed the siege of London. Edmund fought him again, and made him once more raise the siege. When Edmund went into Wessex to gather new forces, Cnut began a third siege, in which, also, 'by God's help,' he made no progress.

In twenty years, therefore, the City of London was besieged six times, and not once taken.

Antiquaries have written a good deal on the colossal nature of the canal constructed by Cnut; they have looked for traces of it in the south of London before it was covered over by houses; they have gone as far afield as Deptford in search of these traces; they have even found them; and to the present day every writer who has mentioned the canal speaks of it and thinks of it with the respect due to a colossal work. Freeman himself called it a 'deep ditch.' How deep it was, how long it was, how broad it was, I am going to explain.

It was in the year 1756 that the painstaking historian, William Maitland, F.R.S., announced that he had been so fortunate as to light upon the course of the long-lost trench of King Cnut.

He had found certain evidence, he said, of its course, in a direction nearly east and west from the then 'New Dock' of Rotherhithe to the river at the end of Chelsea Reach, through Vauxhall Gardens. The proofs were, first, certain depressions in the ground; next, the discovery of oaken planks and piles driven into the ground for what he thought was the northern fence of the canal, near the Old Kent Road; and next a report that, in 1694, when the wet dock of Rotherhithe was constructed, a quantity of hazel, willow, and other branches were found pointing northward, with stakes to keep them in position, forming a kind of water fence, such as, it is said, is still in use in Denmark. It will be seen that Mr. Maitland's theory has but a small basis of evidence, yet it seems to have been generally accepted – partly, I suppose, because it was so colossal.

The canal thus cut would actually be a little over four miles and a half in length. Another writer, seeing the difficulties of so great a work, suggests another course. He would start from the site of the New Dock, Rotherhithe, and end on the other side of London Bridge, a course of only three and three-quarter miles!

Let us ask ourselves why it should be a 'deep' ditch; why it should be a long ditch; why it should be a broad ditch.

Wherever Cnut began his trench, whether at Rotherhithe or nearer the Bridge, he would have the same preliminary difficulties to encounter: that is to say, he would have to cut through the Embankment of the river at either end, and he would have to cut through the Causeway in the middle. In these cuttings he would perhaps have to take down two or three houses, huts, or cabins, all deserted, because the people had all run across the Bridge for safety at the first sight of the Danes, if there were any people at the time living in Southwark – which I doubt.

We may, further, take it for granted that Cnut had officers of sense and experience on whom he could depend for carrying out his canal in a workmanlike manner. A people who could build such perfect ships would certainly not waste time and labour in constructing a trench which would be any longer or deeper or wider than was absolutely necessary.

Now the shortest canal possible would be that in which he was just able to drag his vessels round without destroying the banks. In other words, if a circular canal began at C B, and if we drew an imaginary circle round the middle of the canal, what was required was that the chord D F, forming a tangent to the middle circle, should be at least as long as the longest vessel. Now (see diagram) —

If r is the radius, AD and 2 a the breadth BC, and 2 b the length of the chord DF —

This represents the length of the radius in terms of the length and breadth of the largest vessel in the fleet, and is therefore the smallest radius possible for getting the ships through. Now, the ship of Gokstad, already described, was undoubtedly one of the finest of the vessels used by Danes and Normans. The poets certainly speak of larger ships, but as a marvel. Nothing is said about Cnut bringing over ships of very great size. Now, that vessel was 66 feet in length, considering the keel, which is all we need consider; 16½ feet in breadth, and 4 feet in depth. She drew very little water; therefore a breadth of canal less than the breadth of the vessel was enough. Let us make the chord 70 feet in length, so that b = 35. Let us make the breadth of the canal 12 feet. Therefore 2 a = 12 or a = 6 and r = 105 feet very nearly. Measuring, therefore, 105 feet on either side of London Bridge, we arrive at a possible commencement of Cnut's work. That is to say, if he made a semicircular canal, in that case the length of the canal would be 320 yards, which is certainly an improvement on four miles and a half, or even three miles and three-quarters.

THE GOKSTAD SHIP

There is, however, more to consider. Why should Cnut make a semicircle when an arc would serve his turn? All he had to do was to draw an arc of a circle with the radius just found, to clear any obstacles in the way of approach to the Bridge, and use that arc for his canal. This is most certainly what he did: I am quite certain he adopted this method, because it was the only sensible thing to do. He would thus get off with a canal about fifty yards long, of which the only difficulty would be the cutting through the Embankment and the Causeway.

What would be the depth of the canal? Look at this section of the Gokstad ship. With her breadth of sixteen feet, she had only four feet in depth; without her company and crew, and their arms and provisions, she would thus draw no more than a few inches – certainly not more than eight inches or so. Freeman's deep canal therefore comes to eight inches at the most. But there is still another consideration which lessened the labour materially. The ground behind the Embankment was a little lower than the river at high tide: the Danes, therefore, had only to construct a low wooden containing-wall of timber on each side in order to make their canal without excavating an inch. When that was done, the cutting of the Embankment let in the tide and did the rest. In this simple manner do we reduce Cnut's colossal work of a deep canal, four miles and a half long, into a piece of construction and demolition which would take a large body of men no more than a few hours.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «South London»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «South London» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «South London» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.