John Ashton - The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Ashton - The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On the 18th of September the King arose in his Majesty, and issued a proclamation, with a very long preamble, “strictly commanding and requiring all the Lieutenants of our Counties, and all our Justices of the Peace, Sheriffs, and Under-Sheriffs, and all civil officers whatsoever, that they do take the most effectual means for suppressing all riots and tumults, and to that end do effectually put in execution an Act of Parliament made in the first year of the reign of our late royal ancestor, of glorious memory, King George the First, entituled ‘An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters,’” &c.

Still, in spite of this terrible fulmination, the rioters again “made night hideous” on the 19th of September; but they were not so formidable, nor did they do as much mischief, as on former occasions. On the 20th they made Clare Market their rendezvous , marched about somewhat, had one or two brushes with the St. Clement Danes Association, and, finally, retired on the advent of the Horse Guards. Another mob met in Monmouth Street, the famous old-clothes repository in St. Giles’s, but the Westminster Volunteers, and cavalry, dispersed them; and, the shops shutting very early – much to the discomfiture of the respectable poor, as regarded their Saturday night’s marketings – peace once more reigned. London was once more quiet, and only the rioters who had been captured, were left to be dealt with by the law. But the people in the country were not so quickly satisfied; their wages were smaller than those of their London brethren, and they proportionately felt the pinch more acutely. In some instances they were put down by force, in others the price of bread was lowered; but it is impossible at this time to take up a newspaper, and not find some notice of, or allusion to, a food riot.

The century would die at peace with all men if it could, and there was a means of communication open with France, in the person of a M. Otto, resident in this country as a kind of unofficial agent. The first glimpse we get of these negotiations, from the papers which were published on the subject, is in August, 1800; and between that time, and when the pourparlers came to an end, on the 9th of November, many were the letters which passed between Lord Grenville and M. Otto. Peace, however, was not to be as yet. Napoleon was personally distrusted, and the French Revolution had been so recent, that the stability of the French Government was more than doubted.

A demonstration (it never attained the dimensions of a riot) – this time political and not born of an empty stomach – took place at Kennington on Sunday, the 9th of November. So-called “inflammatory” handbills had been very generally distributed about town a day or two beforehand, calling a meeting of mechanics, on Kennington Common, to petition His Majesty on a redress of grievances.

This actually caused a meeting of the Privy Council, and orders were sent to all the police offices, and the different volunteer corps, to hold themselves in readiness in case of emergency. The precautions taken, show that the Government evidently over-estimated the magnitude of the demonstration. First of all the Bow Street patrol were sent, early in the morning, to take up a position at “The Horns,” Kennington, there to wait until the mob began to assemble, when they were directed to give immediate notice to the military in the environs of London, who were under arms at nine o’clock. Parties of Bow Street officers were stationed at different public-houses, all within easy call.

By and by, about 9 a.m., the conspirators began to make their appearance on the Common, in scattered groups of six or seven each, until their number reached a hundred . Then the police sent round their fiery-cross to summon aid; and before that could reach them, they actually tried the venturesome expedient of dispersing the meeting themselves – with success. But later – or lazier – politicians continued to arrive, and the valiant Bow Street officers, thinking discretion the better part of valour, retired. When, however, they were reinforced by the Surrey Yeomanry, they plucked up heart of grace, and again set out upon their mission of dispersing the meeting – and again were they successful. In another hour, by 10 a.m., these gallant fellows could breathe again, for there arrived to their aid the Southwark Volunteers, and the whole police force from seven offices, together with the river police.

Then appeared on the scene, ministerial authority in the shape of one Mr. Ford, from the Treasury, who came modestly in a hackney coach; and when he arrived, the constables felt the time was come for them to distinguish themselves, and two persons, “one much intoxicated,” were taken into custody, and duly lodged in gaol – and this glorious intelligence was at once forwarded to the Duke of Portland, who then filled the post of Secretary to the Home Department.

The greatest number of people present at any time was about five hundred; and the troops, after having a good dinner at “The Horns,” left for their homes – except a party of horse which paraded the streets of Lambeth. A terrible storm of rain terminated this political campaign, in a manner satisfactory to all; and for this ridiculus mus the Guards, the Horse Guards, and all the military, regulars or volunteers, were under arms or in readiness all the forenoon!

I have here given what, perhaps, some may consider undue prominence to a trifling episode; but it is in these things that the contrast lies as to the feeling of the people, and government, in the dawn of the nineteenth century, and in these latter days of ours. The meeting of a few, to discuss grievances, and to petition for redress, in the one case is met with stern, vigorous repression: in our times a blatant mob is allowed, nay encouraged, to perambulate the streets, yelling, they know not what, against the House of Lords, and the railings of the park are removed, by authority, to facilitate the progress of these Her Majesty’s lieges, and firm supporters of constitutional liberty.

The scarcity of corn still continued down to the end of the year. It had been a bad harvest generally throughout the Continent, and, in spite of the bounty held out for its importation, but little arrived. The markets of the world had not then been opened – and among the marvels of our times, is the large quantity of wheat we import from India, and Australia. So great was this scarcity, that the King, in his paternal wisdom, issued a proclamation (December 3rd) exhorting all persons who had the means of procuring other food than corn, to use the strictest economy in the use of every kind of grain, abstaining from pastry, reducing the consumption of bread in their respective families at least one-third, and upon no account to allow it “to exceed one quartern loaf for each person in each week;” and also all persons keeping horses, especially those for pleasure, to restrict their consumption of grain, as far as circumstances would admit.

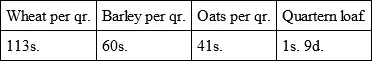

If this proclamation had been honestly acted up to, doubtless it would have effected some relief; which was sorely needed, when we see that the average prices of corn and bread throughout the country were —

And, looking at the difference in value of money then, and now, we must add at least 50 per cent., which would make the average price of the quartern loaf 2s. 7½d.! – and, really, at the end of the year, wheat was 133s. per quarter, bread 1s. 10½d. per quartern.

Three per Cent. Consols were quoted, on January 1, 1800, at 60; on January 1, 1801, they stood at 54.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.