John Ashton - The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Ashton - The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Here is a whole group assembled under the hospitable roof of an umbrella, whilst the exterior circle, for the advantage of having one shoulder dry, is content to receive its dripping contents on the other. The antiquated virgin laments the hour in which, more fearful of a speckle than a wetting, she preferred the dwarfish parasol to the capacious umbrella. The lover regrets there is no shady bower to which he might lead his mistress, ‘nothing loath.’ Happy she who, following fast, finds in the crowd a pretence for closer pressure. Alas! were there but a few grottos, a few caverns, how many Didos – how many Æneas’? Such was the state of the spectators. That of the troops was still worse – to lay exposed to a pelting rain; their arms had changed their mirror-like brilliancy 7 7 The barrels and locks of the muskets of that date were bright and burnished. Browning the gun-barrels for the army was not introduced till 1808.

to a dirty brown; their new clothes lost all their gloss, the smoke of a whole campaign could not have more discoloured them. Where the ground was hard they slipped; where soft, they sunk up to the knee. The water ran out at their cuffs as from a spout, and, filling their half-boots, a squash at every step proclaimed that the Austrian buckets could contain no more.”

CHAPTER III

High price of gold – Scarcity of food – Difference in cost of living 1773-1800 – Forestalling and Regrating – Food riots in the country – Riot in London at the Corn Market – Forestalling in meat.

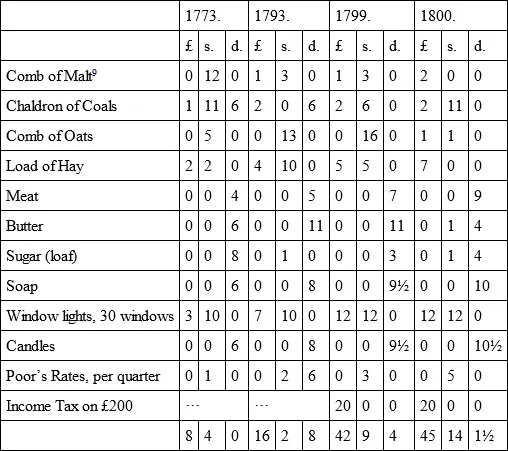

THE PEOPLE were uneasy. Gold was scarce – so scarce, indeed, that instead of being the normal £3 17s. 6d. per oz., it had risen to £4 5s., at which price it was a temptation, almost overpowering, to melt guineas. Food, too, was scarce and dear; and, as very few people starve in silence, riots were the natural consequence. The Acts against “Forestalling and Regrating” – or, in other words, anticipating the market, or purchasing before others, in order to raise the price – were put in force. Acts were also passed giving bounties on the importation of oats and rye, and also permitting beer to be made from sugar. The House of Commons had a Committee on the subject of bread, corn, &c., and they reported on the scarcity of corn, but of course could not point out any practical method of remedying the grievance. The cost of living, too, had much increased, as will appear from the following table of expenses of house-keeping between 1773 and 1800, by an inhabitant of Bury St. Edmunds: 8 8 Annual Register , vol. xlii. p. 94.

Примечание 1 9 9 A comb is four bushels, or half a quarter.

With everything advancing at this amazing rate of progression, it is not to be wondered at that the price of the staff of life was watched very narrowly, and that if there were any law by which any one who enhanced it, artificially, could be punished, he would get full benefit of it, both from judge and jury. Of this there is an instance given in the Annual Register , July 4, 1800:

“This day one Mr. Rusby was tried, in the Court of King’s Bench, on an indictment against him, as an eminent cornfactor, for having purchased, by sample, on the 8th of November last, in the Corn Market, Mark Lane, ninety quarters of oats at 41s. per quarter, and sold thirty of them again in the same market, on the same day, at 44s. The most material testimony on the part of the Crown was given by Thomas Smith, a partner of the defendant’s. After the evidence had been gone through, Lord Kenyon made an address to the jury, who, almost instantly, found the defendant guilty. Lord Kenyon – ‘You have conferred, by your verdict, almost the greatest benefit on your country that was ever conferred by any jury.’ Another indictment against the defendant, for engrossing, stands over.

“Several other indictments for the same alleged crimes were tried during this year, which we fear tended to aggravate the evils of scarcity they were meant to obviate, and no doubt contributed to excite popular tumults, by rendering a very useful body of men odious in the eyes of the mob.”

As will be seen by the accompanying illustration by Isaac Cruikshank, the mob did occasionally take the punishment of forestallers into their own hands. (A case at Bishop’s Clyst, Devon, August, 1800.)

A forestaller is being dragged along by the willing arms of a crowd of country people; the surrounding mob cheer, and an old woman follows, kicking him, and beating him with the tongs. Some sacks of corn are marked 25s. The mob inquire, “How much now, farmer?” “How much now, you rogue in grain?” The poor wretch, half-strangled, calls out piteously, “Oh, pray let me go, and I’ll let you have it at a guinea. Oh, eighteen shillings! Oh, I’ll let you have it at fourteen shillings!”

In August and September several riots, on account of the scarcity of corn, and the high price of provisions, took place in Birmingham, Oxford, Nottingham, Coventry, Norwich, Stamford, Portsmouth, Sheffield, Worcester, and many other places. The markets were interrupted, and the populace compelled the farmers, &c., to sell their provisions, &c., at a low price.

At last these riots extended to London, beginning in a small way. Late at night on Saturday, September 13th, or early on Sunday, September 14th, two large written placards were pasted on the Monument, the text of which was:

How long will ye quietly and cowardly suffer yourselves to be imposed upon, and half starved by a set of mercenary slaves and Government hirelings? Can you still suffer them to proceed in their extensive monopolies, while your children are crying for bread? No! let them exist not a day longer. We are the sovereignty; rise then from your lethargy. Be at the Corn Market on Monday.”

Small printed handbills to the same effect were stuck about poor neighbourhoods, and the chance of a cheap loaf, or the love of mischief, caused a mob of over a thousand to assemble in Mark Lane by nine in the morning. An hour later, and their number was doubled, and then they began hissing the mealmen, and cornfactors, who were going into the market. This, however, was too tame, and so they fell to hustling, and pelting them with mud. Whenever a Quaker appeared, he was specially selected for outrage, and rolled in the mud; and, filling up the time with window breaking, the riot became somewhat serious – so much so, that the Lord Mayor went to Mark Lane about 11 a.m. with some of his suite. In vain he assured the maddened crowd that their behaviour could in no way affect the market. They only yelled at him, “Cheap bread! Birmingham and Nottingham for ever! Three loaves for eighteenpence,” &c. They even hissed the Lord Mayor, and smashed the windows close by him. This proved more than his lordship could bear, so he ordered the Riot Act to be read. The constables charged the mob, who of course fled, and the Lord Mayor returned to the Mansion House.

No sooner had he gone, than the riots began again, and he had to return; but, during the daytime, the mob was fairly quiet. It was when the evening fell, that these unruly spirits again broke out; they routed the constables, broke the windows of several bakers’ shops, and, from one of them, procured a quantity of faggots. Here the civic authorities considered that the riot ought to stop, for, if once the fire fiend was awoke, there was no telling where the mischief might end.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.