Napoleon III - History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Napoleon III - History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We must further mention the projection of land v r , situated below Cartigny. Its form is so regular, and so sharply defined, from the crest to the foot of the talus , that it is difficult not to see in it the vestiges of a work made by men’s hands.

It is easy to estimate approximately the time which it would have taken Cæsar’s troops to construct the 5,000 mètres of trenches which extended, at separate intervals, from Geneva to the Jura.

Let us consider, to fix our ideas, a ground A D V, inclined at 45 degrees, in which is to be made the trench A B C D. The great wall A B C had 16 Roman feet in elevation: we will suppose that A B was inclined at 5 on 1, and that the small wall D C was 6 feet high.

The amount of rubbish removed would be as follows: – Section A B C D = 64 square feet, or, reducing it into square mètres, A B C D = 5 square mètres 60 centimètres.

The mètre in length of the earth thrown out would give thus 5·60 cubic mètres.

If we consider the facility of labour in the trench, since the earth has only to be thrown down the slope, we shall see that two men can dig three mètres in length of this trench in two days. Therefore, admitting that the 10,000 men at Cæsar’s disposal had only been employed a quarter of the time, from two to three days would have been sufficient for the execution of the complete work.

166

De Bello Gallico , I. 8.

167

De Bello Gallico , I. 9. – The country of the Sequani comprised the Jura, and reached to the Pas-de-l’Ecluse. ( See Plate 2 , Map of Gaul.)

168

It has been considered to have been an error of Cæsar to place the Santones in the proximity of the Tolosates: modern researchers have proved that the two peoples were not more than thirty or forty leagues from each other.

169

Several authors have stated wrongly that Cæsar went into Illyria; he informs us himself ( De Bello Gallico , III. 7) that he went thither for the first time in the winter of 698.

170

We believe, with General de Gœler, from the itinerary marked on the Peutingerian table, that the troops of Cæsar passed by Altinum ( Altino ), Mantua, Cremona, Laus Pompei ( Lodi Vecchio ), Pavia, and Turin; but, after quitting this last place, we consider that they followed the route of Fenestrella and Ocelum. Thence they directed their march across the Cottian Alps, by Cesena and Brigantium ( Briançon ); then, following the road indicated by the Theodosian table, which appears to have passed along the banks of the Romanche, they proceeded to Cularo ( Grenoble ), on the frontier of the Vocontii, by Stabatio ( Chahotte or Le Monestier , Hautes-Alpes), Durotineum ( Villards-d’Arenne ), Melloseeum ( Misoen or Bourg-d’Oysans , Isère), and Catorissium ( Bourg-d’Oysans or Chaource , Isère).

171

“Locis superioribus occupatis.” ( De Bello Gallico , I. 10.)

172

There is difference of opinion as to the site of Ocelum. The following remark has been communicated to me by M.E. Celesia, who is preparing a work on ancient Italy: Ocelum only meant, in the ancient Celtic or Iberian language, principal passage . We know that, in the Pyrenees, these passages were called ports . There existed places of the name of Ocelum , in the Alps, in Gaul, and as far as Spain. (Ptolemy, II. 6.) – The itineraries found in the baths of Vicarello indicate, between Turin and Susa, an Ocelum , which appears to us to have been that of which Cæsar speaks; there was a place similarly named in Maurienne, on the left bank of the Arc, at an equal distance from the source of that river and the town of Saint-Jean; it is now Usseglio . There was another in the valley of the Lanzo, on the left bank of the Gara, from which appears to be derived the name of Garaceli or Graioceli; it was called Ocelum Lanciensium . The Ocelum of Cæsar, according to M. Celesia, who adopts the opinion of D’Anville, was called Ocelum ad Clusonem fluvium ; it was situated in the valley of the Pragelatto, on the road leading from Pignerol to the defile of Fenestrella. This place has continued to preserve its primitive name of Ocelum , Occelum , Oxelum , Uxelum ( Charta Adeladis , an. 1064), whence by corruption its modern name of Usseau . According to this hypothesis, Cæsar would have passed from the valley of Chiusone into that of Pragelatto, and thence, by Mount Genèvre, to Briançon, in order to arrive among the Vocontii. – Polyænus ( Stratag. , VIII. xxiii. 2) relates that Cæsar took advantage of a mist to escape the mountaineers.

173

“Segusiavi sunt trans Rhodanum primi.” ( De Bello Gallico , I. 10.) It is to be supposed that there existed a bridge on the Rhone, near Lyons.

174

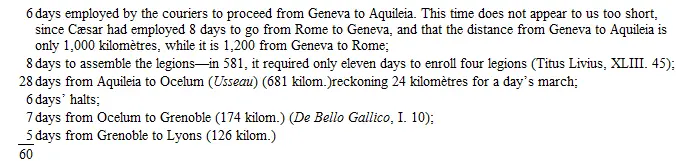

Cæsar had deferred his reply till the Ides of April (April the 8th). If it were then decided to bring the legions from Aquileia, the time necessary to bring them would have been as follows:

According to this reckoning, Cæsar required 60 days, reckoning from the moment when he decided on this course, to transport his legions from Aquileia to Lyons; that is to say, if he sent, as is probable, couriers on the 8th of April, the day he refused the passage to the Helvetii, the head of his column arrived at Lyons towards the 7th of June.

175

To estimate the volume and weight represented by the provisions for three months for three hundred and sixty-eight thousand persons of both sexes and of all ages, let us allow that the ration of food was small, and consisted, we may say, only in a reserve of meal, trium mensium molita cibaria , at an average of ¾ of a pound (¾ of a pound of meal gives about a pound of bread); at this rate, the Helvetii must have carried with them 24,840,000 pounds, or 12,420,000 kilogrammes of meal. Let us allow also that they had great four-wheeled carriages, capable each of carrying 2,000 kilogrammes, and drawn by four horses. The 100 kilogrammes of unrefined meal makes 2 cubic hectolitres; therefore, 2,000 kilogrammes of meal make 4 cubic mètres, so that this would lead us to suppose no more than 4 cubic mètres as the average load for the four-wheeled carriages. On our good roads in France, levelled and paved, three horses are sufficient to draw, at a walking pace, during ten hours, a four-wheeled carriage carrying 4,000 kilogrammes. It is more than 1,300 kilogrammes per collar.

We suppose that the horses of the emigrants drew only 500 kilogrammes in excess of the dead weight, which would give about 6,000 carriages and 24,000 draught animals to transport the three months’ provisions.

But these emigrants were not only provided with food, for they had also certainly baggage. It appears to us no exaggeration to suppose that each individual carried, besides his food, fifteen kilogrammes of baggage on an average. We are thus left to add to the 6,000 provision carriages about 2,500 other carriages for the baggage, which would make a total of 8,500 carriages drawn by 34,000 draught animals. We use the word animals instead of horses, as at least a part of the teams would, no doubt, be composed of oxen, the number of which would diminish daily, for the emigrants would be led to use the flesh of these animals for their own food.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «History of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.