John Ruskin - Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Ruskin - Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_home, architecture_book, literature_19, visual_arts, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

12. This being so, you see that when the relative beauty of any particular forms has to be examined, we may reason, from the forms of Nature around us, in this manner:—what Nature does generally, is sure to be more or less beautiful; what she does rarely, will either be very beautiful, or absolutely ugly. And we may again easily determine, if we are not willing in such a case to trust our feelings, which of these is indeed the case, by this simple rule, that if the rare occurrence is the result of the complete fulfillment of a natural law, it will be beautiful; if of the violation of a natural law, it will be ugly. For instance, a sapphire is the result of the complete and perfect fulfillment of the laws of aggregation in the earth of alumina, and it is therefore beautiful; more beautiful than clay, or any other of the conditions of that earth. But a square leaf on any tree would be ugly, being a violation of the laws of growth in trees, 5and we ought to feel it so.

13. Now then, I proceed to argue in this manner from what we see in the woods and fields around us; that as they are evidently meant for our delight, and as we always feel them to be beautiful, we may assume that the forms into which their leaves are cast, are indeed types of beauty, not of extreme or perfect, but average beauty. And finding that they invariably terminate more or less in pointed arches, and are not square-headed, I assert the pointed arch to be one of the forms most fitted for perpetual contemplation by the human mind; that it is one of those which never weary, however often repeated; and that therefore, being both the strongest in structure, and a beautiful form (while the square head is both weak in structure, and an ugly form), we are unwise ever to build in any other.

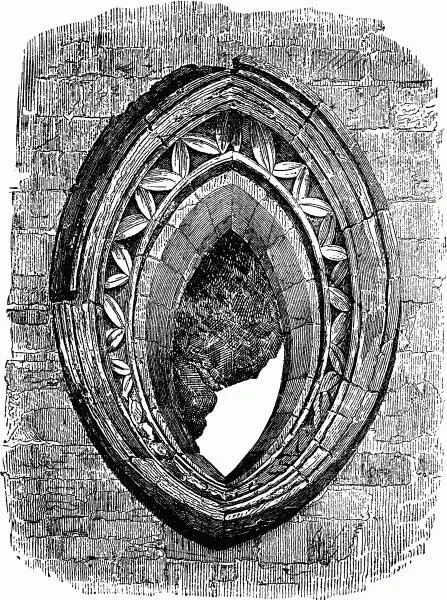

Fig. 7.

PLATE IV.

14. Here, however, I must anticipate another objection. It may be asked why we are to build only the tops of the windows pointed,—why not follow the leaves, and point them at the bottom also?

For this simple reason, that, while in architecture you are continually called upon to do what may be unnecessary for the sake of beauty, you are never called upon to do what is inconvenient for the sake of beauty. You want the level window sill to lean upon, or to allow the window to open on a balcony: the eye and the common sense of the beholder require this necessity to be met before any laws of beauty are thought of. And besides this, there is in the sill no necessity for the pointed arch as a bearing form; on the contrary, it would give an idea of weak support for the sides of the window, and therefore is at once rejected. Only I beg of you particularly to observe that the level sill, although useful, and therefore admitted, does not therefore become beautiful; the eye does not like it so well as the top of the window, nor does the sculptor like to attract the eye to it; his richest moldings, traceries, and sculptures are all reserved for the top of the window; they are sparingly granted to its horizontal base. And farther, observe, that when neither the convenience of the sill, nor the support of the structure, are any more of moment, as in small windows and traceries, you instantly have the point given to the bottom of the window. Do you recollect the west window of your own Dunblane Abbey? If you look in any common guide-book, you will find it pointed out as peculiarly beautiful,—it is acknowledged to be beautiful by the most careless observer. And why beautiful? Look at it ( fig. 7). Simply because in its great contours it has the form of a forest leaf, and because in its decoration it has used nothing but forest leaves. The sharp and expressive molding which surrounds it is a very interesting example of one used to an enormous extent by the builders of the early English Gothic, usually in the form seen in fig. 2, Plate II., composed of clusters of four sharp leaves each, originally produced by sculpturing the sides of a four-sided pyramid, and afterwards brought more or less into a true image of leaves, but deriving all its beauty from the botanical form. In the present instance only two leaves are set in each cluster; and the architect has been determined that the naturalism should be perfect. For he was no common man who designed that cathedral of Dunblane. I know not anything so perfect in its simplicity, and so beautiful, as far as it reaches, in all the Gothic with which I am acquainted. And just in proportion to his power of mind, that man was content to work under Nature's teaching; and instead of putting a merely formal dogtooth, as everybody else did at the time, he went down to the woody bank of the sweet river beneath the rocks on which he was building, and he took up a few of the fallen leaves that lay by it, and he set them in his arch, side by side, forever. And, look—that he might show you he had done this,—he has made them all of different sizes, just as they lay; and that you might not by any chance miss noticing the variety, he has put a great broad one at the top, and then a little one turned the wrong way, next to it, so that you must be blind indeed if you do not understand his meaning. And the healthy change and playfulness of this just does in the stone-work what it does on the tree boughs, and is a perpetual refreshment and invigoration; so that, however long you gaze at this simple ornament—and none can be simpler, a village mason could carve it all round the window in a few hours—you are never weary of it, it seems always new.

15. It is true that oval windows of this form are comparatively rare in Gothic work, but, as you well know, circular or wheel windows are used constantly, and in most traceries the apertures are curved and pointed as much at the bottom as the top. So that I believe you will now allow me to proceed upon the assumption, that the pointed arch is indeed the best form into which the head either of door or window can be thrown, considered as a means of sustaining weight above it. How these pointed arches ought to be grouped and decorated, I shall endeavor to show you in my next lecture. Meantime I must beg of you to consider farther some of the general points connected with the structure of the roof.

16. I am sure that all of you must readily acknowledge the charm which is imparted to any landscape by the presence of cottages; and you must over and over again have paused at the wicket gate of some cottage garden, delighted by the simple beauty of the honeysuckle porch and latticed window. Has it ever occurred to you to ask the question, what effect the cottage would have upon your feelings if it had no roof ? no visible roof, I mean;—if instead of the thatched slope, in which the little upper windows are buried deep, as in a nest of straw—or the rough shelter of its mountain shales—or warm coloring of russet tiles—there were nothing but a flat leaden top to it, making it look like a large packing-case with windows in it? I don't think the rarity of such a sight would make you feel it to be beautiful; on the contrary, if you think over the matter, you will find that you actually do owe, and ought to owe, a great part of your pleasure in all cottage scenery, and in all the inexhaustible imagery of literature which is founded upon it, to the conspicuousness of the cottage roof—to the subordination of the cottage itself to its covering, which leaves, in nine cases out of ten, really more roof than anything else. It is, indeed, not so much the whitewashed walls—nor the flowery garden—nor the rude fragments of stones set for steps at the door—nor any other picturesqueness of the building which interest you, so much as the gray bank of its heavy eaves, deep-cushioned with green moss and golden stone-crop. And there is a profound, yet evident, reason for this feeling. The very soul of the cottage—the essence and meaning of it—are in its roof; it is that, mainly, wherein consists its shelter; that, wherein it differs most completely from a cleft in rocks or bower in woods. It is in its thick impenetrable coverlet of close thatch that its whole heart and hospitality are concentrated. Consider the difference, in sound, of the expressions "beneath my roof" and "within my walls,"—consider whether you would be best sheltered, in a shed, with a stout roof sustained on corner posts, or in an inclosure of four walls without a roof at all,—and you will quickly see how important a part of the cottage the roof must always be to the mind as well as to the eye, and how, from seeing it, the greatest part of our pleasure must continually arise.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)