John George Wood - Nature's Teachings

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John George Wood - Nature's Teachings» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Издательство: Иностранный паблик, Жанр: foreign_antique, Природа и животные, foreign_edu, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nature's Teachings

- Автор:

- Издательство:Иностранный паблик

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nature's Teachings: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nature's Teachings»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nature's Teachings — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nature's Teachings», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At the bottom of the illustration is shown the poison-fang of a Spider, which, as the reader may see, is formed just on the principle of the scorpion-sting.

So much for animal poisons. We will now pass to the vegetable world.

Of the vegetable sting-bearers none are more familiar to us than the Nettle, three species of which inhabit this country. The two commonest are the Great Nettle ( Urtica diœcea ) and the Small Nettle ( Urtica urens ), and both of them are armed with venomous stings, which cause the plants to be so much dreaded.

The structure of these stings is very simple, and can be made out with an ordinary microscope, or even a good pocket lens. Each of these stings is, in fact, a rather elaborately constructed hair, hollow throughout its length, coming to a point at the tip, and having the base swollen into a receptacle containing the poisonous juice. When any object—such, for example, as the human hand—touches a nettle, the points of the stings slightly penetrate the skin, and the hair is pressed downwards against the base, so that the poison is forced through the hole.

One of these hairs is shown in the left-hand bottom corner of the illustration.

Even the tiny stings of our English nettles are sufficiently venomous to cause considerable pain, and, in some cases, even to affect the whole nervous system. But some of the exotic nettles are infinitely more formidable, and are, indeed, so dangerous that, when they are grown in a botanical garden, a fence is placed round them, so as to prevent visitors even from touching a single leaf.

The two most dreaded species are called Urtica heterophylla and Urtica crenulata . The former is thought to be the more dangerous of the two, and a good idea of its venomous qualities may be gathered from an account of an adventure with Urtica crenulata . The narrator is M. L. de la Tour.

“One of the leaves slightly touched the first three fingers of my left hand; at the time I only perceived a slight pricking, to which I paid no attention. This was at seven in the morning. The pain continued to increase, and in an hour it became intolerable; it seemed as if some one were rubbing my fingers with a hot iron. Nevertheless, there was no remarkable appearance, neither swelling, nor pustules, nor inflammation.

“The pain spread rapidly along the arm as far as the armpit. I was then seized with frequent sneezing, and with a copious running at the nose, as if I had caught a violent cold in the head. About noon I experienced a painful attack of cramp at the back of the jaws, which made me fear an attack of tetanus. I then went to bed, hoping that repose would alleviate my suffering, but it did not abate. On the contrary, it continued nearly the whole of the following night; but I lost the contraction of the jaws about seven in the evening.

“The next morning the pain began to leave me, and I fell asleep. I continued to suffer for two days, and the pain returned in full force when I put my hand into water. I did not finally lose it for nine days.”

There is another of these formidable nettles, called in the East by a name which signifies “Devil’s Leaf,” and which is sufficiently venomous to cause death. There is but little doubt, however, that in the present instance, if a larger portion of the body—say the whole arm—instead of three fingers, had been stung, death would have ensued from the injury.

We now come to another improvement, or rather addition, in the various piercing weapons. Sometimes, as in the case of the dagger or the hand-spear, it was necessary that when a blow had been struck the weapon should be easily withdrawn from the wound, so as not to disarm the assailant, and to enable him to repeat the stroke if needful. But in the case of a missile weapon, such as a javelin or an arrow, it was often useful, both in war and hunting, to form the head in such a way that when it had once entered it could scarcely be withdrawn. For this purpose the Barb was invented, taking different forms, according to the object of the weapon and the nationality of the maker.

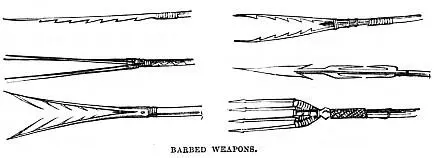

As in this work I prefer to show the gradual development of human inventions, I shall take my examples of barbs entirely from the weapons of uncivilised nations, six examples of which are given in the accompanying illustration, and five of them being drawn from specimens in my collection.

The upper left-hand figure is rather a curious one, the position of the barbs being nearly reversed, so that they serve to tear the flesh rather than adhere to it. The opposite figure represents an arrow with a doubly barbed point. It is chiefly used for shooting fish as they lie dozing on or near the surface of the water, but it is an effective weapon for ordinary hunting purposes, and, as the shaft is fully five feet in length, is quite formidable enough for war.

The left-hand bottom figure represents a very remarkable instrument, for it can hardly be called a weapon, and is, in fact, the head of a policeman’s staff. It is peculiar to Java, and is called by the name of “Bunday.” As may be seen by reference to the illustration, the head of the Bunday is formed of two diverging slips of wood. To each of these is lashed a row of long and sharp thorns, all pointing inwards, and the whole is attached to a tolerably long shaft.

When a prisoner is brought before the chief, a policeman stands behind him, armed with the Bunday, and, if the man should try to escape, he is immediately arrested by thrusting the weapon at him, so as to catch him by the waist, neck, or arm, or a leg. Escape is impossible, especially as in Java the prisoner wears nothing but his waist-cloth.

A weapon formed on exactly the same principle was used in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and was employed for dragging knights off their horses. It was of steel instead of wood, and the place of the thorns was taken by two movable barbs, working on hinges, and kept open by springs. When a thrust was made at the knight’s neck the barbs gave way, so as to allow the prongs to envelop the throat, and they then sprang back again, preventing the horseman from disengaging himself. This weapon is technically named a “catchpoll.”

An illustration of one of these weapons will be given on another page.

The right-hand central figure is an arrow from Western Africa. In a previous illustration (page 65) a head of one of these arrows is given on rather a larger scale, so as to show the very peculiar barbs. These are of such a nature that when they have well sunk into the body they cannot be withdrawn, but must be pushed through, and drawn out on the opposite side. This is drawn from one of my own specimens.

In some cases, with an almost diabolical ingenuity, the native arrow-maker has set on a couple of similar barbs, directed towards the point, so that the weapon can neither be pushed through nor drawn back. One of these arrows is shown in the illustration, but, for want of space, the artist has placed the opposing barbs too near each other.

In some parts of Southern Africa a similar weapon was used for securing a prisoner, the barbed point being thrust down his throat and left there. If it were pushed through the neck it killed him on the spot, and if it remained in the wound the man could not eat nor drink, and the best thing for him was to die as soon as he could.

With similar ingenuity, the Tongans and Samoans made their war-spears with eight or nine barbs, and, before going into action, used to cut the wood almost through between each barb, so that when the body was pierced, the head, with several of the barbs, was sure to break off and leave a large portion in the wound. In Mariner’s well-known book there is an admirable account of the mode employed by a native surgeon for extracting one of these spear-heads. So common was this weapon that every Tongan gentleman carried a many-barbed spear about five feet long, and used it either as a walking-stick or a weapon. It is needless to say that this spear is almost an exact copy of the tail-bone of the Stingray. A dagger made of this bone was used in the Pelew Islands in 1780, but seemed to be rather scarce.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nature's Teachings»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nature's Teachings» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nature's Teachings» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.