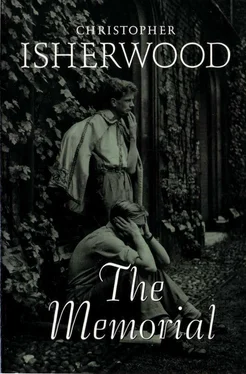

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Yes, Mrs. Vernon, I promise."

She poured him out another cup of tea. Looking him smilingly straight in the eyes, without embarrassment :

"There's a favour I've been meaning to ask you for some time."

His heart seemed to swell:

"Yes?"

"I should like it very much if you would call me Lily. May I call you Ronald?"

He bowed his head—could hardly trust himself to speak:

"Yes, please do," he managed to say.

She leant back a little in her chair, lightly yet beautifully dismissing the subject:

"Thank you. It seemed rather absurd to be so formal, now that we are friends."

This brought tea to an end. They sat for some time silent. Ronald was aware of the silence of the

lamplit flat, high up in the great building, above the intense crawling movement of the far-away traffic. It was as quiet and isolated as a shrine. Lily sat thoughtfully gazing before her, at her hand with its single pale-shining gold ring. She asked:

"Tell me, Ronald. If you had your life to live again, would you alter anything?"

He considered her question. It was the first time he had ever been asked it. He was unaccustomed to talk about himself.

"I think," he said carefully at length, "I might have been better off in a cavalry regiment. But it was a question of money at the time. It was impossible to live on one's pay."

Perhaps this had not been quite what she had meant, for she said, with a faint smile:

"I suppose everything is so different for a man."

He considered this carefully also:

"Yes, I think it must be."

Lily smiled gaily.

"Men always seem to me so restless and discontented in comparison with women. They'll do anything to make a change, even when it leaves them worse off."

He must have made some faintly deprecatory movement, for she said:

"Oh, yes, they will! You know you would yourself, if you got the opportunity."

She smiled; she laughed at him with a strange

note of opposition, as though holding him back at arm's distance.

"Whereas," she added, "we women, we only want peace."

He did not answer. She pressed him, almost mockingly:

"I suppose you think that sounds very selfish?"

He replied gravely, with a certain dignity:

"I'm afraid I can't believe that you're being quite sincere."

She laughed strangely.

"Perhaps I'm not; I don't know."

There was a silence. He wished he had not said that. It seemed that she had opened some door, only to shut it again. They avoided each other's eyes, and when Lily spoke, it was to change the subject:

"You know something about silver, don't you?"

"Only a very little."

She rose, smiling:

"Have I ever shown you this?"

Opening a cupboard, she took out a box padded with cotton - wool, unwrapped several layers, brought it across to the light of the lamp.

"As a matter of fact," she said, "I'm sure you can't have seen it, because it has been in the Bank since the War. I've only just got it out."

"It's beautiful," he said, turning the shallow, heavy dish over in his hands.

"It's supposed to be Jacobean."

Ronald examined it carefully:

"Yes. I should say it must be very valuable."

"I believe it is. It belonged to my aunt. She gave it me as a wedding present."

Lily thoughtfully put the dish down on the table. It stood there between them. Then she spoke, not sadly, but with a quiet note of wonder, as if to herself:

"How perfectly extraordinary it seems to think that I'm still alive and the dish is still here. It's like something dug up from another civilisation."

He was silent. He feared by the least word to jar upon her mood. She continued:

"The modern idea seems to be that the old people should enjoy themselves and go about just like the young ones. That there shouldn't be any distinction. They should dress alike and talk alike and do their best to look alike."

She paused, gazing into the shadows.

"I think, myself, that happiness belongs to young people. Old people have got memories."

She was so beautiful as she said that, that Ronald might have interrupted, protested, told her that she wasn't old, but young—would always be young. But he was awed by her strange, rapt manner. She spoke dreamily, like one delivering oracles:

"I think that if one has been very very happy for part of one's life, then nothing else matters."

She added, after a moment, as though pursuing the same line of thought:

"I wish you and Richard could have known each other. I think you would have had a great deal in common."

He sat quite silent, could not reply. She smiled. She said quite simply:

"I've sometimes felt that he is pleased we are friends."

The lift slid down its shaft. He had passed out of the flat, it seemed, like a somnambulist; was walking with long strides through the lamplit streets.

Now, at last, he could value, as never before, the beauty of his treasure—their friendship. Walking erect like a hero, swinging his umbrella, he knew himself to be the most fortunate, the most privileged, as the most unworthy of living men. And this great happiness was not realised too late, about to come to an end. It would go on and on. Week would follow week. I shall see her, he thought. I shall speak to her. We shall have tea together. We shall talk.

And to think that only this morning he'd been tormenting himself with ridiculous madman's hopes, schemes, illusions. He had considered his meagre bank balance, his pension, his little flat. Yes, he'd been ready to commit that supreme folly, that insolence. They could never have met again. He saw now that she'd have interpreted his proposal as a sort of treachery, a betrayal of his trust, his honoured position. He was ready to agree now that it would have been a betrayal.

How beautifully she had saved him from that folly, the misery of her refusal. How beautifully she'd indicated what their relationship must be. She must have read his thoughts, for surely her every word that afternoon had been a warning, exquisitely conveyed. How gladly he accepted it. For he knew now that he could be of some small service to her, and that was all he had ever really hoped. It was enough of happiness.

If I had met her as a boy, he thought—not supposing that then things might have happened otherwise, but thinking: If I had met her then, how much better my life would have been. It is women like her, he thought, who raise men from the brutes they are. Without them we could be nothing. She is a saint, he thought. I have known a saint.

Tired, walking more slowly, he stopped at last before a door which seemed familiar. It was his Club. The few fellow-members who nodded to him, as he passed through the smoking-room and sat down in his favourite chair, remarked that Charlesworth was actually a quarter of an hour late. Usually, you could set your watch by him— any of his three dining nights in the week.

III

"And so I'm taking myself off," Edward wrote, trying to steady his hand against the vibration of the little table. "I rely on you to make the peace with Mary. For God's sake, invent some extraordinarily subtle reason for my departure, and be sure to write and tell me exactly what it is. Then I can send her a Christmas card. The truth is merely that I had a sudden dazzling vision of what it will be like at the Gowers' and at the Kleins', and on New Year's Eve at Mrs. Gidden's. And it was too much for me. Please forgive this, certainly not my last, betrayal."

They were well beyond Hannover; had finished lunch. The sad level plains, unfenced, dotted with woods, rotated smoothly beyond the thick pane curtained with green baize to prevent the least draught. The dining-car smelt richly of the cigars of stout shaven-skulled passengers with student scars on their cheeks. Edward's light impertinent eye surveyed them, his fingers drumming the stem of his glass.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.