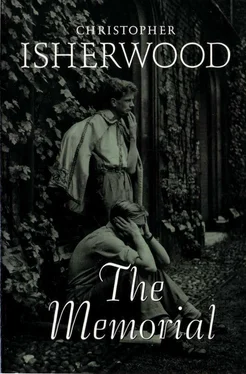

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

From this, and from many other incidents of lesser importance, Eric had learnt that there was a very feminine side to Maurice's nature. He was soft, like a girl. And yet this slim, delicate-looking boy would not only do things which the Ramsbothams would never have dared, but even made their very insensitive nerves tingle on his account. More than once Gerald had cried out involuntarily: "Steady on, Maurice!" They would take

risks themselves, but he would do things which were purely mad—dancing about on the parapet of the mill roof, riding down the Brow backwards on his bike at top speed, or fooling about in a punt on the river and pretending that he was going to shoot the weir. He was wonderfully agile and erratically brilliant at tennis and cricket—but not at all physically strong. Eric could have put him on the ground without an effort. Sometimes he baited Billy Hawkes and the Ramsbothams until they lost their tempers with him and punished him soundly. On these occasions, after screams of agony, he merely laughed, showing neither resentment at their tortures nor the least shame at his own weakness.

Anne was not spectacular, like Maurice. She was quiet. She quietly fitted into the picture which Eric had formed for himself of the life of his cousins and his aunt in their little house—as the life of beings altogether singular, more gifted, happier than other people. It was this life of the Scrivens, as he saw it, that he had fallen in love with. He liked to imagine the three of them together in their home, at all times of the day—calling to each other from room to room, running up and down stairs, weaving, like shuttles, the strands of their existence, which seemed so mysterious to Eric because it was so happy.

The house was usually full of people. Aunt Mary would be holding a committee meeting in the

sitting-room. In the dining-room there was often another committee meeting or a rehearsal, to which she would come and attend presently. Maurice's friends gathered in his bedroom or ran about the garden. Anne belonged to both worlds. She helped at the rehearsals, sometimes sat on the committees, lent a hand in the kitchen with whatever meal was preparing, mended socks, and then came running out to make up a four at tennis. The boys all liked her. She was admirable with Gerald and Tommy, who often kissed her in semi-serious horseplay: for she was handsome, though not exactly pretty. She was very dark, like her brother, with a bold forehead, too broad for a girl, and eyes drawn down at the corners, giving her at moments a wise, kindly, rather masculine appearance. But she didn't affect tomboyishness. She didn't wish or attempt to be taken on the same terms as one of themselves. The other day Billy Hawkes, moved by some impulse, had held a door open for her. She had walked through first, quite naturally, like a grown-up woman. It had given Eric a slight shock of recognition that they were all growing up. Anne had left school very young, because—as Eric had been told (they made no bones about it)—Aunt Mary couldn't afford to educate both her and Maurice in the proper style; and education was more important for a boy. Maurice went to a good public school, while Anne helped her mother with the house and Gatesley affairs.

This morning, in the churchyard, Anne had asked Eric to help them with the school picnic. Maurice was coming. They were to have charge of a special party. "And I want you to keep an eye on him," she had said. "You know what Maurice is. He mustn't take them climbing in the quarry."

So they trusted him. They treated him as one of themselves. They saw in Eric no fatal deficiency, no reason why he should not be regarded as normal, sane. Absurd as it was, he couldn't help dwelling on these assurances with the most exquisite pleasure. It seemed to him that, if he could live always with his cousins, he would expand like a flower, breaking out of his own clumsy identity, gaining strength and confidence. At that moment, at the thought of seeing them so soon, he was extraordinarily happy; he was transfigured with happiness. He stood on his pedals as he raced through the park. In less than five minutes he was in the village street, bouncing along over the setts, whistling piercingly. Several people stared. It occurred to Eric suddenly that he was recognised as the Squire's grandson, many people must know him by sight—and of course they were thinking it very strange that he should be racing about Chapel Bridge, whistling so loud, on a day like this. Perhaps they even know where I'm going to, he thought. He blushed violently, slowed down, then speeded up again, to escape them, up the steep side

street, past the Sunday school, past the doctor's, past the Conservative Club.

But a moment later he had forgotten his self-consciousness. He was thinking that it would be well worth while to win an entrance scholarship to Cambridge, to work and become a don, if only to fulfil the opinion which Maurice and Anne had of him. For they had—or pretended to have, Eric added—a great respect for his cleverness. Maurice sighed at the mention of exams. "I wish I was you, Eric," he had said. And that afternoon Eric was full of confidence. He wouldn't fail them, if he had to work like a nigger. This, at least, he could do to be worthy of his cousins.

One afternoon, when he'd been riding over to see the Scrivens, Eric had had an idea which he'd later tried to put into a poem. Chapel Bridge and Gatesley were like the two poles of a magnet. Chapel Bridge—the blank asphalt and brick village, his village, clean, urban, dead—he called the negative pole. Gatesley—their village, lying so romantically in the narrow valley, its grey stone cottages surrounded by the sloping moors—that was the positive pole. And if you rode over from Chapel Bridge to Gatesley, from Gatesley back to Chapel Bridge, you were like a pin on a bit of metal filing, being drawn first by one pole, then by the other. That was where the poem had broken down, because a pin would never move between the poles at all, but fly to one and stick there. Also, "magnet" is

an awkward-sounding word to get into a sonnet. Anyhow, Eric had the sensation, although he couldn't express it as well as he would have liked. As he climbed the hill to the waterworks he felt the strong negative pull of Chapel Bridge trying to drag him backwards like a harness. The Hall was behind it. His mother. All the morning's scruples. The War Memorial itself. But as he passed the waterworks, as he climbed the hill to Ridge top, the field strength of Chapel Bridge grew weaker. Weaker it grew, until the neutral point was reached, the farm which stood at the last corkscrew of the road. A few yards more, and the faint pull of Gatesley could already be felt. And now Aunt Mary and Maurice and Anne were drawing him forward, so that it seemed no effort to jump on to his bicycle and pedal up the last of the slope.

From the Ridge you could see right out across Cheshire—on a clear day, to the mountains. At night, the lights of Manchester, Stockport and Hyde were sprinkled over the north-western plain, seemed sometimes to quiver and move in the tremendous cataract of air pouring over the hills. And when there had been a snowfall, Kinder Scout looked awful and lonely with black outcrops of rock, under a bare sky. One year the Downfall had frozen to an enormous icicle, reflecting the red sun. Stone walls criss-crossed the wild, bleak country spreading towards Macclesfield Forest and the

Peak. Maurice had become an expert on ordnance maps, and though he seldom walked further than he could help, he reeled off, within a few months of coming to Gatesley, names which Eric had never heard, fascinating him: Hoo Moor, Flash, Stoop, Adder's Green. At the top of the Ridge it was always cool; though Cheshire lay trembling in haze. Eric got off his bicycle for a few moments, liking to stand there, feeling on one hand the lonely country of cart-roads, broken sign-posts, stone farms and walls, on the other the solemn wilderness of tram-lines and brick and the tall mills scribbling the sky with their smoke.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.