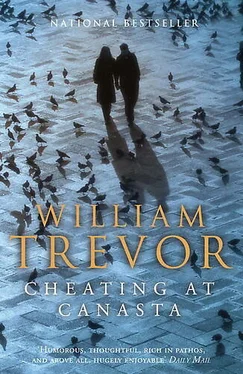

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The boy looked up from the playing cards he had spread out on the floor. ‘What’s his name?’ he asked, and Miss Davally said he knew because she had told him already. But even so she did so again. ‘Why’s he called that?’ Anthony asked. ‘Why’re you called that?’

‘It’s my name.’

‘Shall we play in the garden?’

That first day, and every day afterwards, there were gingersnap biscuits in the middle of the morning. ‘Am I older than you?’ Anthony asked. ‘Is six older?’ He had a house, he said, in the bushes at the end of the garden, and they pretended there was a house. ‘Jericho he’s called,’ Anthony said of the dog that followed them about, a black Labrador with an injured leg that hung limply, thirteen years old. ‘Miss Davally is an orphan,’ Anthony said. ‘That’s why she lives with us. Do you know what an orphan is?’

In the yard the horses looked out over the half-doors of their stables; the hounds were in a smaller yard. Anthony’s mother was never at lunch because her horse and the hounds were exercised then. But his father always was, each time wearing a different tweed jacket, his grey moustache clipped short, the olives he liked to see on the lunch table always there, the whiskey he took for his health. ‘Well, young chap, how are you?’ he always asked.

On wet days they played marbles in the kitchen passages, the dog stretched out beside them. ‘You come to the sea in summer,’ Anthony said. ‘They told me.’ Every July: the long journey from Westmeath to the same holiday cottage on the cliffs above the bay that didn’t have a name. It was Miss Davally who had told Anthony all that, and in time—so that hospitality might be returned—she often drove Anthony there and back. An outing for her too, she used to say, and sometimes she brought a cake she’d made, being in the way of bringing a present when she went to people’s houses. She liked it at the sea as much as Anthony did; she liked to turn the wheel of the bellows in the kitchen of the cottage and watch the sparks flying up; and Anthony liked the hard sand of the shore, and collecting flintstones, and netting shrimps. The dog prowled about the rocks, sniffing the seaweed, clawing at the sea-anemones. ‘Our house,’ Anthony called the cave they found when they crawled through an opening in the rocks, a cave no one knew was there.

Air from the window Wilby slightly opens at the top is refreshing and brings with it, for a moment, the chiming of two o’clock. His book is open, face downward to keep his place, his bedside light still on. But the dark is better, and he extinguishes it.

There was a blue vase in the recess of the staircase wall, nothing else there; and paperweights crowded the shallow landing shelves, all touching one another; forty-six, Anthony said. His mother played the piano in the drawing-room. ‘Hullo,’ she said, holding out her hand and smiling. She wasn’t much like someone who exercised foxhounds: slim and small and wearing scent, she was also beautiful. ‘Look!’ Anthony said, pointing at the lady in the painting above the mantelpiece in the hall.

Miss Davally was a distant relative as well as being an orphan, and when she sat on the sands after her bathe she often talked about her own childhood in the house where she’d been given a home: how a particularly unpleasant boy used to creep up on her and pull a cracker in her ear, how she hated her ribboned pigtails and persuaded a simple-minded maid to cut them off, how she taught the kitchen cat to dance and how people said they’d never seen the like.

Every lunchtime Anthony’s father kept going a conversation about a world that was not yet known to his listeners. He spoke affectionately of the playboy pugilist Jack Doyle, demonstrating the subtlety of his right punch and recalling the wonders of his hell-raising before poverty claimed him. He told of the exploits of an ingenious escapologist, Major Pat Reid. He condemned the first Earl of Inchiquin as the most disgraceful man ever to step out of Ireland.

Much other information was passed on at the lunch table: why aeroplanes flew, how clocks kept time, why spiders spun their webs and how they did it. Information was everything, Anthony’s father maintained, and its lunchtime dissemination, with Miss Davally’s reminiscences, nurtured curiosity: the unknown became a fascination. ‘What would happen if you didn’t eat?’ Anthony wondered; and there were attempts to see if it was possible to create a rainbow with a water hose when the sun was bright, and the discovery made that, in fact, it was. A jellyfish was scooped into a shrimp net to see if it would perish or survive when it was tipped out on to the sand. Miss Davally said to put it back, and warned that jellyfish could sting as terribly as wasps.

A friendship developed between Miss Davally and Wilby’s mother—a formal association, first names not called upon, neither in conversation nor in the letters that came to be exchanged from one summer to the next. Anthony is said to be clever , Miss Davally’s spidery handwriting told. And then, as if that perhaps required watering down, Well, so they say . It was reported also that when each July drew near Anthony began to count the days. He values the friendship so! Miss Davally commented. How fortunate for two only children such a friendship is!

Fortunate indeed it seemed to be. There was no quarrelling, no vying for authority, no competing. When, one summer, a yellow Lilo was washed up, still inflated, it was taken to the cave that no one else knew about, neither claiming that it was his because he’d seen it first. ‘Someone lost that thing,’ Anthony said, but no one came looking for it. They didn’t know what it was, only that it floated. They floated it themselves, the dog limping behind them when they carried it to the sea, his tail wagging madly, head cocked to one side. In the cave it became a bed for him, to clamber on to when he was tired.

The Lilo was another of the friendship’s precious secrets, as the cave itself was. No other purpose was found for it, but its possession was enough to make it the highlight of that particular summer and on the last day of July it was again carried to the edge of the sea. ‘Now, now,’ the dog was calmed when he became excited. The waves that morning were hardly waves at all.

In the dark there is a pinprick glow of red somewhere on the television set. The air that comes into the room is colder and Wilby closes the window he has opened a crack, suppressing the murmur of a distant plane. Memory won’t let him go now; he knows it won’t and makes no effort to resist it.

Nothing was said when they watched the drowning of the dog. Old Jericho was clever, never at a loss when there was fun. Not moving, he was obedient, as he always was. He played his part, going with the Lilo when it floated out, a deep black shadow, sharp against the garish yellow. They watched as they had watched the hosepipe rainbow gathering colour, as Miss Davally said she’d watched the shaky steps of the dancing cat. Far away already, the yellow of the Lilo became a blur on the water, was lost, was there again and lost again, and the barking began, and became a wail. Nothing was said then either. Nor when they climbered over the shingle and the rocks, and climbed up to the short-cut and passed through the gorse field. From the cliff they looked again, for the last time, far out to the horizon. The sea was undisturbed, glittering in the sunlight. ‘So what have you two been up to this morning?’ Miss Davally asked. The next day, somewhere else, the dog was washed in.

Miss Davally blamed herself, for that was in her nature. But she could not be blamed. It was agreed that she could not be. Unaware of his limitations—more than a little blind, with only three active legs—old Jericho had had a way of going into the sea when he sensed a piece of driftwood bobbing about. Once too often he had done that. His grave was in the garden, a small slate plaque let into the turf, his name and dates.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.