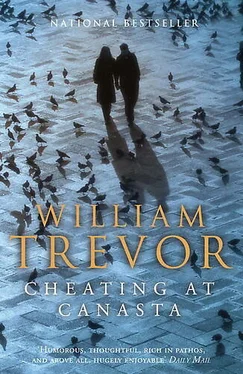

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘What d’you want?’ she shouted at the letterbox.

Fingers appeared, pressing the flap open.

‘Excuse me, missus. Excuse me, but there’s someone lying down in your garden.’

‘It’s half past six in the morning.’

‘Could you phone up the guards, missus?’

In the hall she shook her head, not answering that. She asked whereabouts in her garden the person was.

‘Just lying there on the grass. I’d call them up myself only my mobile’s run out.’

She telephoned. No point in not, she thought. She was glad to be leaving this house, which for so long had been too big for two and was now ridiculously big for one. She had been glad before this, but now was more certain than ever that she had made the right decision. She thought so again while she watched from her dining-room window a Garda car arriving, and an ambulance soon after that. She opened her hall door then, and saw a body taken away. A man came to speak to her, saying it was he who had talked to her through the letterbox. A guard told her the person they had found lying near her eleagnus was dead.

On the news the address was not revealed. A front garden, it was reported, and gave the district. A milkman going by on his way to the depot had noticed. No more than that.

When Aisling came down at five past eight they were talking about it in the kitchen. She knew at once.

‘You all right?’ her mother asked, and she said she was. She went back to her bedroom, saying she had forgotten something.

It was all there on the front page of the Evening Herald ’s early-afternoon edition. No charges had been laid, but it was expected that they would be later in the day. The deceased had not been known to the householder in whose garden the body had been discovered, who was reported as saying she had not been roused by anything unusual in the night. The identity of the deceased had not yet been established, but a few details were given, little more than that a boy of about sixteen had met his death following an assault. Witnesses were asked to come forward.

Aisling didn’t; the girl who had tagged along did. The victim’s companion on the walk from the Star nightclub gave the time they left it, and the approximate time of their parting from one another. The nightclub bouncers were helpful but could add little to what was already known. The girl who had come forward was detained for several hours at the Garda station from which enquiries were being made. She was complimented on the clarity of her evidence and pressed to recall the names of the four people she had been with. But she had never known those names, only that the red-haired boy was called Mano and had himself addressed two of his companions as ‘cowboy’. Arrests were made just before midnight.

Aisling read all that the next morning in the Irish Independent , which was the newspaper that came to the house. Later in the day she read an almost identical account in the Irish Times , which she bought in a newsagent’s where she wasn’t known. Both reports referred to her, describing her as ‘the second girl’, whom the gardaí´ were keen to locate. There was a photograph, a coat thrown over the head and shoulders of a figure being led away, a wrist handcuffed to that of a uniformed Garda. The second arrest, at a house in Ranelagh, told no more. No names were released at first.

When they were, Aisling made a statement, confessing that she was the second girl, and in doing so she became part of what had happened. People didn’t attempt to talk to her about it, and at the convent it was forbidden that they should do so; but it was sometimes difficult, even for strangers, to constrain the curiosity that too often was evident in their features. When more time passed there was the trial, and then the verdict: acquitted of murder, the two who had been apprehended were sent to gaol for eleven years, their previous good conduct taken into account, together with the consideration, undenied by the court, that there was an accidental element in what had befallen them: neither had known of their victim’s frail, imperfect heart.

Aisling’s father did not repeat his castigation of her for making a friendship he had never liked: what had happened was too terrible for petty blame. And her father, beneath an intolerant surface, could draw on gentleness, daily offering comfort to the animals he tended. ‘We have to live with this,’ he said, as if accepting that the violence of the incident reached out for him too, that guilt was indiscriminately scattered.

For Aisling, time passing was stranger than she had ever known days and nights to be before. Nothing was unaffected. In conveying the poetry of Shakespeare on the hastily assembled convent stage she perfectly knew her lines, and the audience was kind. But there was pity in that applause, because she had unfairly suffered in the aftermath of the tragedy she had witnessed. She knew there was, and in the depths of her consciousness it felt like mockery and she did not know why.

A letter came, long afterwards, flamboyant handwriting bringing back the excitement of surreptitious notes in the past. No claim was made on her, nor were there protestations of devotion, as once, so often, there had been. He would go away. He would bother no one. He was a different person now. A priest was being helpful.

The letter was long enough for contrition, but still was short. Missing from its single page was what had been missing, also, during the court hearing: that the victim had been a nuisance to Donovan’s sister. In the newspaper photograph—the same one many times—Dalgety had been dark-haired, smiling only slightly, his features regular, almost nondescript except for a mole on his chin. And seeing it so often, Aisling had each time imagined his unwanted advances pressed on Hazel Donovan, and had read the innocence in those features as a lie. It was extraordinary that this, as the reason for the assault, had not been brought forward in the court; and more extraordinary that it wasn’t touched upon in a letter where, with remorse and regret, it surely belonged. ‘Some guy comes on heavy,’ Donovan, that night, had said.

There had been a lingering silence and he broke it to mention this trouble in his family, as if he thought that someone should say something. The conversational tone of his voice seemed to indicate he would go on, but he didn’t. Hungry for mercy, she too eagerly wove into his clumsy effort at distraction an identity he had not supplied, allowing it to be the truth, until time wore the deception out.

After the convent, Aisling acquired a qualification that led to a post in the general office of educational publishers. She had come to like being alone and often in the evenings went on her own to the cinema, and at weekends walked at Howth or by the sea at Dalkey. One afternoon she visited the grave, then went back often. A stone had been put there, its freshly incised words brief: the name, the dates. People came and went among the graves but did not come to this one, although flowers were left from time to time.

In a bleak cemetery Aisling begged forgiveness of the dead for the falsity she had embraced when what there was had been too ugly to accept. Silent, she had watched an act committed to impress her, to deserve her love, as other acts had been. And watching, there was pleasure. If only for a moment, but still there had been.

She might go away herself, and often thought she would: in the calm of another time and place to flee the shadows of bravado. Instead she stayed, a different person too, belonging where the thing had happened.

An Afternoon

Jasmin knew he was going to be different, no way he couldn’t be, no way he’d be wearing a baseball cap backwards over a number-one cut, or be gawky like Lukie Giggs, or make the clucking noise that Darren Finn made when he was trying to get a word out. She couldn’t have guessed; all she knew was he wouldn’t be like them. Could be he’d put you in mind of the Rawdeal drummer, whatever his name was, or of Al in Doc Martin . But the boy at the bus station wasn’t like either. And he wasn’t a boy, not for a minute.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.