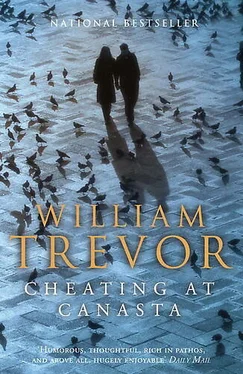

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The kir he’d asked for came. He ordered turbot, a Caesar salad first. He pointed at a Gavi that had not been on the wine list before. ‘ Perfetto !’ the waiter approved.

There was a pretence that Julia could still play cards, and in a way she could. On his visits they would sit together on the sofa in the drawing-room of her confinement and challenge one another in another game of Canasta, which so often they had played on their travels or in the garden of the house they’d lived in since their marriage, where their children had been born. ‘No matter what,’ Julia had said, aware then of what was coming, ‘let’s always play cards.’ And they did; for even with her memory gone, a little more of it each day—her children taken, her house, her flowerbeds, belongings, clothes—their games in the communal drawing-room were a reality her affliction still allowed. Not that there was order in their games, not that they were games at all; but still her face lit up when she found a joker or a two among her cards, was pleased that she could do what her visitor was doing, even though she couldn’t quite, even though once in a while she didn’t know who he was. He picked up from the floor the Kings and Jacks, the eights and tens her fumbling fingers dropped. He put them to one side, it didn’t matter where. He cheated at Canasta and she won.

The promise Julia had exacted from her husband had been her last insistence. Perturbation had already begun, a fringe of the greyness that was to claim her so early in her life. Because, tonight, he was alone where so often she had been with him, Mallory recalled with piercing rawness that request and his assent to it. He had not hesitated but had agreed immediately, wishing she had asked for something else. Would it have mattered much, he wondered in the crowded restaurant, if he had not at last made this journey, the first of the many she had wanted him to make? In the depths of her darkening twilight, if there still were places they belonged in a childhood he had not known, among shadows that were hers, not his, not theirs. In all that was forgotten how could it matter if a whim, forgotten too, was put aside, as the playing cards that fell from her hand were?

A table for six was lively in a corner, glasses raised; a birthday celebration it appeared to be. A couple who hadn’t booked, or had come too early, were sent away. A tall, thin woman looked about her, searching for someone who wasn’t there. The last time, Mallory remembered, their table had been by the door.

He went through the contents of his wallet: the familiar cards, the list of the telephone numbers he always brought abroad, some unused tickets for the Paris Métro, scraps of paper with nothing on them, coloured slips unnecessarily retained. Its carte bancaire stapled to it, the bill of his hotel in Paris was folded twice and was as bulky as his tidy wad of euro currency notes. Lisa someone had scribbled on the back of a fifty. His wine came.

He had travelled today from Monterosso, from the coast towns of the Cinque Terre, where often in September they had walked the mountain paths. The journey in the heat had been uncomfortable. He should have broken it, she would have said—a night in Milan, or Brescia to look again at the Foppas and the convent. Of course he should have arranged that, Mallory reflected, and felt foolish that he hadn’t, and then foolish for being where he was, among people who were here for pleasure, or reasons more sensible than his. It was immediately a relief when a distraction came, his melancholy interrupted by a man’s voice.

‘Why are you crying?’ an American somewhere asked.

This almost certainly came from the table closest to his own, but all Mallory could see when he slightly turned his head was a salt-cellar on the corner of a tablecloth. There was no response to the question that had been asked, or none that he heard, and the silence that gathered went on. He leaned back in his chair, as if wishing to glance more easily at a framed black-and-white photograph on the wall—a street scene dominated by a towering flat-iron block. From what this movement allowed, he established that the girl who had been asked why she was crying wasn’t crying now. Nor was there a handkerchief clenched in the slender, fragile-seeming fingers on the tablecloth. A fork in her other hand played with the peas on her plate, pushing them about. She wasn’t eating.

A dressed-up child too young even to be at the beginning of a marriage, but instinctively Mallory knew that she was already the wife of the man who sat across the table from her. A white band drew hair as smooth as ebony back from her forehead. Her dress, black too, was severe in the same way, unpatterned, its only decoration the loop of a necklace that matched the single pearl of each small earring. Her beauty startled Mallory—the delicacy of her features, her deep, unsmiling eyes—and he could tell that there was more of it, lost now in the empty gravity of her discontent.

‘A better fellow than I am.’ Her husband was ruddy, hair tidily brushed and parted, the knot of a red silk tie neither too small nor clumsily large in its crisp white collar, his linen suit uncreased. Laughing slightly when there was no response, either, to his statement about someone else being a better fellow, he added: ‘I mean, the sort who gets up early.’

Mallory wondered if they were what he’d heard called Scott Fitzgerald people, and for a moment imagined he had wondered it aloud—as if, after all, Julia had again come to Venice with him. It was their stylishness, their deportment, the young wife’s beauty, her silence going on, that suggested Scott Fitzgerald, a surface held in spite of an unhappiness. ‘Oh but,’ Julia said, ‘he’s careless of her feelings.’

‘ Prego, signore .’ The arrival of Mallory’s Caesar salad shattered this interference with the truth, more properly claiming his attention and causing him to abandon his pretence of an interest in something that wasn’t there. It was a younger waiter who brought the salad, who might even be the boy—grown up a bit—whom Julia had called the primo piatto boy and had tried her Italian on. While Mallory heard himself wished buon appetito , while the oil and vinegar were placed more conveniently on the table, he considered that yes, there was a likeness, certainly of manner. It hadn’t been understood by the boy at first when Julia asked him in Italian how long he’d been a waiter, but then he’d said he had begun at Harry’s Bar only a few days ago and had been nowhere before. ‘ Subito, signore ,’ he promised now when Mallory asked for pepper, and poured more wine before he went away.

‘I didn’t know Geoffrey got up early.’ At the table that was out of sight her voice was soft, the quietness of its tone registering more clearly than what it conveyed. Her husband said he hadn’t caught this. ‘I didn’t know he got up early,’ she repeated.

‘It’s not important that he does. It doesn’t matter what time the man gets up. I only said it to explain that he and I aren’t in any way alike.’

‘I know you’re not like Geoffrey.’

‘Why were you crying?’

Again there was no answer, no indistinct murmur, no lilt in which words were lost.

‘You’re tired.’

‘Not really.’

‘I keep not hearing what you’re saying.’

‘I said I wasn’t tired.’

Mallory didn’t believe she hadn’t been heard: her husband was closer to her than he was and he’d heard the ‘Not really’ himself. The scratchy irritation nurtured malevolence unpredictably in both of them, making her not say why she had cried and causing him to lie. My God, Mallory thought, what they are wasting!

‘No one’s blaming you for being tired. No one can help being tired.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.