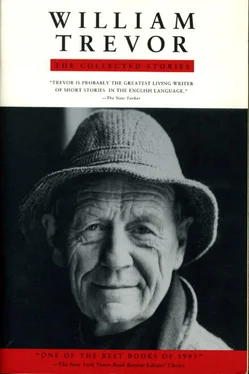

William Trevor - Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: Penguin Publishing, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Horgan’s Picture House,’ he said. ‘I wonder is it still going strong?’

She shook her head. She said she didn’t know if Horgan’s Picture House was still standing, since she had never been to the town he spoke of.

‘I first saw Gracie Fields there,’ he revealed. ‘And Jack Hulbert in a funny called Round the Washtub. ’

They were reclining in deck-chairs on a terrace of the Hôtel Les Galets in Bandol, looking out at the Mediterranean. Mimosa and bougainvillaea bloomed around them, oranges ripened, palm trees flapped in a small breeze, and on a pale-blue sky the sun pushed hazy clouds aside. With her friend Miss Grimshaw, Miss Ticher always came to Bandol in late April, between the mistral and the season, before the noise and the throbbing summer heat. They had known one another for more than thirty years and when, next year, they both retired at sixty-five they planned to live in a bungalow in Sevenoaks, not far from St Mildred’s School for Girls, where Miss Ticher taught history and Miss Grimshaw French. They would, they hoped, continue to travel in the spring to Bandol, to the quiet Mediterranean and the local bouillabaisse, their favourite dish.

Miss Ticher was a thin woman with a shy face and frail, thin hands. She had been asleep on the upper terrace of Les Galets and had wakened to find the untidy man standing in front of her. He had asked if he might sit in the deck-chair beside hers, the chair that Miss Grimshaw had earlier planned to occupy on her return from her walk. Miss Ticher felt she could not prevent the man from sitting down, and so had nodded. He was not staying in the hotel, he said, and added that his business was that of a detective. He was observing a couple who were at present in an upstairs room: it would facilitate his work if Miss Ticher would kindly permit him to remain with her and perhaps engage in a casual conversation while he awaited the couple’s emergence. A detective, he told Miss Ticher, could not be obvious: a detective must blend with the background, or at least seem natural. ‘The So-Swift Investigation Agency’, he said. ‘A London firm’. As he lowered himself into the chair that Miss Grimshaw had reserved for herself he said he was an exiled Irishman. ‘Did you ever hear of the Wild Geese?’ he enquired. ‘Soldiers of fortune? I often feel like that myself. My name is Quillan.’

He was younger than he looked, she thought: forty-five, she estimated, and seeming to be ten years older. Perhaps it was that, looking older than he was, or perhaps it was the uneasy emptiness in his eyes, that made her feel sorry for him. His eyes apologized for himself, even though he attempted to hide the apology beneath a jauntiness. He wouldn’t be long on the terrace, he promised: the couple would soon be checking out of the hotel and on behalf of the husband of the woman he would discreetly follow them, around the coast in a hired Renault. It was work he did not much care for, but it was better than other work he had experienced: he’d drifted about, he added with a laugh, from pillar to post. With his eyes closed in the warmth he talked about his childhood memories while Miss Ticher listened.

‘Youghal,’ he said. ‘I was born in Youghal, in County Cork. In 1934 my mother went in for a swim and got caught up with a current. My dad went out to fetch her and they both went down.’

He left his deck-chair and went away, and strangely she wondered if perhaps he was going to find a place to weep. An impression of his face remained with her: a fat red face with broken veins in it, and blue eyes beneath dark brows. When he smiled he revealed teeth that were stained and chipped and not his own. Once, when laughing over a childhood memory, they had slipped from their position in his jaw and had had to be replaced. Miss Ticher had looked away in embarrassment, but he hadn’t minded at all. He wasn’t a man who cared about the way he struck other people. His trousers were held up with a tie, his pale stomach showed through an unbuttoned shirt. There was dandruff in his sparse fluff of sandy hair and on the shoulders of a blue blazer: yesterday’s dandruff, Miss Ticher had thought, or even the day before’s.

‘I’ve brought you this,’ he said, returning and sitting again in Miss Grimshaw’s chair. He proffered a glass of red liquid. ‘A local aperitif.’

Over pots of geraniums and orange-tiled roofs, across the bay and the green sea that was ruffled with little bursts of foam, were the white villas of Sanary, set among cypresses. Nearer, and more directly below, was the road to Toulon and beyond it a scrappy beach on which Miss Ticher now observed the figure of Miss Grimshaw.

‘I was given over to the aunt and uncle,’ said Quillan, ‘on the day of the tragedy. Although, as I’m saying to you, I don’t remember it.’

He drank whisky mixed with ice. He shook the liquid in his glass, watching it. He offered Miss Ticher a cigarette, which she refused. He lit one himself.

‘The uncle kept a shop,’ he said.

She saw Miss Grimshaw crossing the road to Toulon. A driver hooted; Miss Grimshaw took no notice.

‘Memories are extraordinary,’ said Quillan, ‘the things you’d remember and the things you wouldn’t. I went to the infant class at the Loreto Convent. There was a Sister Ita. I remember a woman with a red face who cried one time. There was a boy called Joe Murphy whose grandmother kept a greengrocer’s. I was a member of Joe Murphy’s gang. We used to fight another gang.’

Miss Grimshaw passed from view. She would be approaching the hotel, moving slowly in the warmth, her sunburnt face shining as her spectacles shone. She would arrive panting, and already, in her mind, Miss Ticher could hear her voice. ‘What on earth’s that red stuff you’re drinking?’ she’d demand in a huffy manner.

‘When I was thirteen years old I ran away from the aunt and uncle,’ Quillan said. ‘I hooked up with a travelling entertainments crowd that used to go about the seaside places. I think the aunt must have been the happy female that day. She couldn’t stand the sight of me.’

‘Oh surely now –’

‘Listen,’ said Quillan, leaning closer to Miss Ticher and staring intently into her eyes. ‘I’ll tell you the way this case was. You’d like to know?’

‘Well –’

‘The uncle had no interest of any kind in the bringing up of a child. The uncle’s main interest was drinking bottles of stout in Phelan’s public house, with Harrigan the butcher. The aunt was a different kettle of fish: the aunt above all things wanted nippers of her own. For the whole of my thirteen years in that house I was a reminder to my aunt of her childless condition. I was a damn nuisance to both of them.’

Miss Ticher, moved by these revelations, did not know what to say. His eyes were slightly bloodshot, she saw; and then she thought it was decidedly odd, a detective going on about his past to an elderly woman on the terrace of an hotel.

‘I wasn’t wanted in that house,’ he said. ‘When I was five years old she told me the cost of the food I ate.’

It would have been 1939 when he was five, she thought, and she remembered herself in 1939, a girl of twenty-four, just starting her career at St Mildred’s, a girl who’d begun to feel that marriage, which she’d wished for, might not come her way. ‘We’re neither of us the type,’ Miss Grimshaw later said. ‘We’d be lost, my dear, without the busy life of school.’

She didn’t want Miss Grimshaw to arrive on the terrace. She wanted this man who was a stranger to her to go on talking in his sentimental way. He described the town he spoke of: an ancient gateway and a main street, and a harbour where fishing boats went from, and the strand with wooden breakwaters where his parents had drowned, and seaside boarding-houses and a promenade, and short grass on a clay hill above the sea.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.