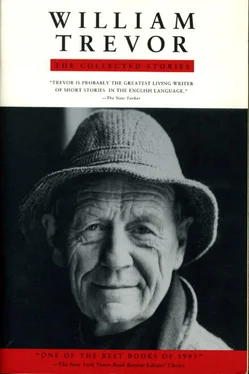

William Trevor - Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: Penguin Publishing, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With deft strokes the General cleared his face of lather and whisker, savouring the crisp rasp of razor upon flesh. He used a cut-throat article and when shorn to his satisfaction wiped it on a small absorbent pad, one of a series he had collected from the bedrooms of foreign hotels. He washed, dressed, set his moustache as he liked to sport it, and descended to his kitchen.

The General’s breakfast was simple: an egg poached lightly, two slices of toast and a pot of tea. It took him ten minutes to prepare and ten to consume. As he finished he heard the footsteps of the woman who daily came to work for him. They were slow, dragging footsteps implying the bulk they gracelessly shifted. The latch of the door rose and fell and Mrs Hinch, string bags and hairnet, cigarette cocked from the corner of her mouth, stood grinning before him. ‘Hullo,’ this woman said, adding as she often did, ‘my dear.’

‘Good morning, Mrs Hinch.’

Mrs Hinch stripped herself of bags, coat and cigarette with a single complicated gesture. She grinned again at the General, replaced her cigarette and set to clearing the table.

‘I shall walk to the village this morning,’ General Suffolk informed her. ‘It seems a pleasant morning to dawdle through. I shall take coffee at the brown café and try my luck at picking up some suitable matron.’

Mrs Hinch was accustomed to her employer’s turn of speech. She laughed shrilly at this sally, pleased that the man would be away for the morning. ‘Ah, General, you’ll be the death of us,’ she cried; and planned for his absence a number of trunk calls on his telephone, a leisurely bath and the imbibing of as much South African sherry as she considered discreet.

‘It is Saturday if I am not mistaken,’ the General went on. ‘A good morning for my plans. Is it not a fact that there are stout matrons in and out of the brown café by the score on a Saturday morning?’

‘Why, sure, General,’ said Mrs Hinch, anxious to place no barrier in his way. ‘Why, half the county goes to the brown café of a Saturday morning. You are certain to be successful this time.’

‘Cheering words, Mrs Hinch, cheering words. It is one thing to walk through the campion-clad lanes on a June morning, but quite another to do so with an objective one is sanguine of achieving.’

‘This is your day, General. I feel it in my bones. I said it to Hobson as I left. “This is a day for the General,” I said. “The General will do well today,” I said.’

‘And Hobson, Mrs Hinch? Hobson replied?’

Again Mrs Hinch, like a child’s toy designed for the purpose, shrilled her merriment.

‘General, General, Hobson’s my little bird.’

The General, rising from the table, frowned. ‘Do you imagine I am unaware of that? Since for six years you have daily informed me of the fact. And why, pray, since the bird is a parrot, should the powers of speech be beyond it? It is not so with other parrots.’

‘Hobson’s silent, General. You know Hobson’s silent.’

‘Due to your lethargy, Mrs Hinch. No bird of his nature need be silent: God does not intend it. He has taken some pains to equip the parrot with the instruments of speech. It is up to you to pursue the matter in a practical way by training the animal. A child, Mrs Hinch, does not remain ignorant of self-expression. Nor of the ability to feed and clean itself. The mother teaches, Mrs Hinch. It is part of nature. So with your parrot.’

Enthusiastic in her own defence, Mrs Hinch said: ‘I have brought up seven children. Four girls and three boys.’

‘Maybe. Maybe. I am in no position to question this. But indubitably with your parrot you are flying in the face of nature.’

‘Oh, General, never. Hobson’s silent and that’s that.’

The General regarded his adversary closely. ‘You miss my point,’ he said drily; and repeating the remark twice he left the room.

In his time General Suffolk had been a man of more than ordinary importance. As a leader and a strategist in two great wars he had risen rapidly to the heights implied by the title he bore. He had held in his hands the lives of many thousands of men; his decisions had more than once set the boundaries of nations. Steely intelligence and physical prowess had led him, in their different ways, to glories that few experience at Roeux; and at Monchy-le-Preux he had come close to death. Besides all that, there was about the General a quality that is rare in the ultimate leaders of his army: he was to the last a rake, and for this humanity a popular figure. He had cared for women, for money, for alcohol of every sort; but in the end he had found himself with none of these commodities. In his modest cottage he was an elderly man with a violent past; with neither wife nor riches nor cellar to help him on his way.

Mrs Hinch had said he would thrive today. That the day should be agreeable was all he asked. He did not seek merriness or reality or some moment of truth. He had lived for long enough to forgo excitement; he had had his share; he wished only that the day, and his life in it, should go the way he wished.

In the kitchen Mrs Hinch scoured the dishes briskly. She was not one to do things by halves; hot water and detergent in generous quantities was her way.

‘Careful with the cup handles,’ the General admonished her. ‘Adhesive for the repair of such a fracture has apparently not yet been perfected. And the cups themselves are valuable.’

‘Oh they’re flimsy, General. So flimsy you can’t watch them. Declare to God, I shall be glad to see the last of them!’

‘But not I, Mrs Hinch. I like those cups. Tea tastes better from fine china. I would take it kindly if you washed and dried with care.’

‘Hoity-toity, General! Your beauties are safe with me. I treat them as babies.’

‘Babies? Hardly a happy analogy, Mrs Hinch – since five of the set are lost for ever.’

‘Six,’ said Mrs Hinch, snapping beneath the water the handle from the cup. ‘You are better without the bother of them. I shall bring you a coronation mug.’

‘You fat old bitch,’ shouted the General. ‘Six makes the set. It was my last remaining link with the gracious life.’

Mrs Hinch, understanding and wishing to spite the General further, laughed. ‘Cheery-bye, General,’ she called as she heard him rattling among his walking sticks. He banged the front door and stepped out into the heat of the day. Mrs Hinch turned on the wireless.

‘I walked entranced,’ intoned the General, ‘ through a land of morn. The sun in wondrous excess of light …’ He was seventy-eight: his memory faltered over the quotation. His stick, weapon of his irritation, thrashed through the campions, covering the road with broken blooms. Grasshoppers clicked; bees darted, paused, humming in flight, silent in labour. The road was brown with dust, dry and hot in the sunlight. It was a day, thought the General, to be successfully in love; and he mourned that the ecstasy of love on a hot summer’s day was so far behind him. Not that he had gone without it; which gave him his yardstick and saddened him the more.

Early in his retirement General Suffolk had tried his hand in many directions. He had been, to start with, the secretary of a golf club; though in a matter of months his temper relieved him of the task. He was given to disagreement and did not bandy words. He strode away from the golf club, red in the face, the air behind him stinging with insults. He lent his talents to the business world and to a military academy: both were dull and in both he failed. He bought his cottage, agreeing with himself that retirement was retirement and meant what it suggested. Only once since moving to the country had he involved himself with salaried work: as a tennis coach in a girls’ school. Despite his age he was active still on his legs and managed well enough. Too well, his grim and beady-eyed headmistress avowed, objecting to his method of instructing her virgins in the various stances by which they might achieve success with the serve. The General paused only to level at the headmistress a battery of expressions well known to him but new to her. He went on his way, his cheque in his wallet, his pockets bulging with small articles from her study. The girls he had taught pursued him, pressing upon him packets of cheap cigarettes, sweets and flowers.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.