James Gleick - Time Travel

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Gleick - Time Travel» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Time Travel

- Автор:

- Издательство:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Time Travel: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Time Travel»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Time Travel — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Time Travel», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Story is our only boat for sailing on the river of time.

—Ursula K. Le Guin (1994)

YOUR NOW IS not my now. You’re reading a book. I’m writing a book. You’re in my future, yet I know what comes next—some of it—and you don’t. *1

Then again, you can be a time traveler in your own book. If you’re impatient, you can skip ahead to the ending. When memory fails you, just turn back the page. It’s all there in writing. You’re well acquainted with time traveling by page turning, and so, for that matter, are the characters in your books. “I don’t know how to put it exactly,” says Aomame in Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, “but there is a sense of time wavering irregularly when you try to forge ahead. If what is in front is behind, and what is behind is in front, it doesn’t really matter, does it?” Soon she appears to be changing her own reality—but you, the reader, can’t change history, nor can you change the future. What will be, will be. You are outside it all. You are outside of time.

If this seems a bit meta, it is. In the era of time travel rampant, storytelling has gotten more complicated.

Literature creates its own time. It mimics time. Until the twentieth century, it did that mainly in a sensible, straightforward, linear way. The stories in books usually began at the beginning and ended at the end. A day might pass or many years but usually in order. Time was mostly invisible. Occasionally, though, time came to the foreground. From the beginning of storytelling, there have been stories told inside other stories, and these shift time as well as place: flashbacks and flash-forwards. So aware are we of storytelling that sometimes a character in a story will feel like a character in a story, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, at time’s mercy: Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow… Or perhaps we here in real life develop a nagging suspicion that we are mere characters in someone else’s virtual reality. Players performing a script. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern imagine they are masters of their fate, and who are we to know better? The omniscient narrator of Michael Frayn’s 2012 novel Skios says of the characters living in his story, “If they had been living in a story, they might have guessed that someone somewhere had the rest of the book in his hands, and that what was just about to happen was already there in the printed pages, fixed, unalterable, solidly existent. Not that it would have helped them very much, because no one in a story ever knows they are.”

In a story one thing comes after another. That is its defining feature. The story is a recital of events. We want to know what happens next. We keep listening, we keep reading, and with any luck the king lets Scheherazade live for one night more. At least this was the traditional view of narrative: “Events arranged in their time sequence,” as E. M. Forster said in 1927—“dinner coming after breakfast, Tuesday after Monday, decay after death, and so on.” In real life we enjoy a freedom that the storyteller lacks. We lose track of time, we drift and dream. Our past memories pile up, or spontaneously intrude on our thoughts, our expectations for the future float free, but neither memories nor hopes organize themselves into a timeline. “It is always possible for you or me in daily life to deny that time exists and act accordingly even if we become unintelligible and are sent by our fellow citizens to what they choose to call a lunatic asylum,” said Forster. “But it is never possible for a novelist to deny time inside the fabric of his novel.” In life we may hear the ticking clock or we may not; “whereas in a novel,” he said, “there is always a clock.”

Not anymore. We have evolved a more advanced time sense—freer and more complex. In a novel there may be multiple clocks, or no clocks, conflicting clocks and unreliable clocks, clocks running backward and clocks spinning aimlessly. “The dimension of time has been shattered,” wrote Italo Calvino in 1979; “we cannot love or think except in fragments of time each of which goes off along its own trajectory and immediately disappears. We can rediscover the continuity of time only in the novels of that period when time no longer seemed stopped and did not yet seem to have exploded, a period that lasted no more than a hundred years.” He doesn’t say exactly when the hundred years ended.

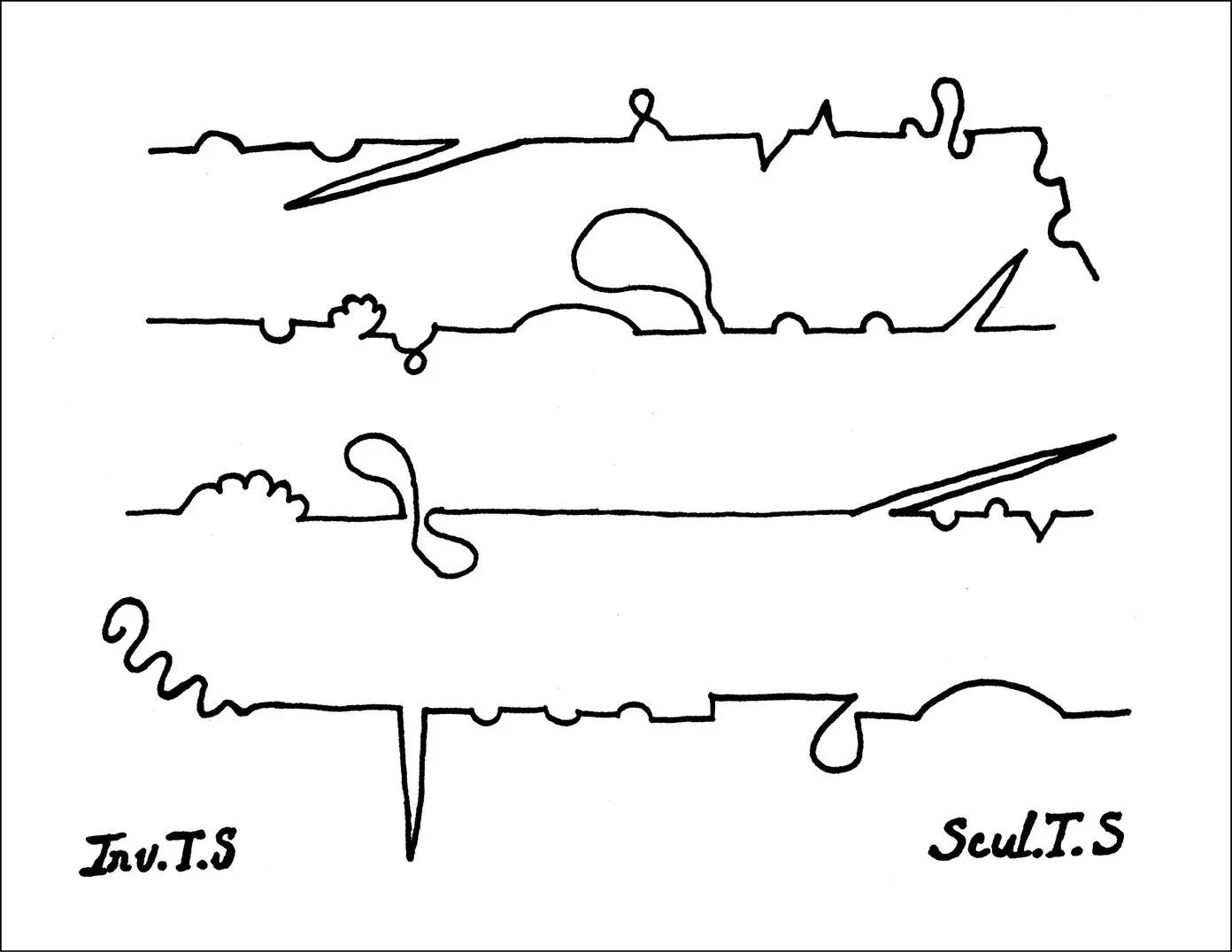

Forster might have known he was oversimplifying, with modernist movements rising self-consciously all around. He had read Emily Brontë, who rebelled against chronological time in Wuthering Heights. He had read Laurence Sterne, whose Tristram Shandy had “a hundred difficulties which I have promised to clear up, and a thousand distresses and domestic misadventures crowding in upon me thick and threefold” and threw off the shackles of tense—“A cow broke in (tomorrow morning) to my uncle Toby’s fortifications”—and even diagrammed his temporal divagation with a timeline of squiggles, back and forth, up and around.

Credit 13.1

Forster had read Proust, too. But I’m not sure he had gotten the message: that time was busting out all over.

It had seemed that space was our natural dimension: the one we move about in, the one we sense directly. To Proust we became denizens of the time dimension: “I would describe men, even at the risk of giving them the appearance of monstrous beings, as occupying in Time a much greater place than that so sparingly conceded to them in Space, a place indeed extended beyond measure…like giants plunged in the years, they touch at once those periods of their lives—separated by so many days—so far apart in Time.” *2Marcel Proust and H. G. Wells were contemporaries, and while Wells invented time travel by machine, Proust invented a kind of time travel without one. We might call it mental time travel—and meanwhile psychologists have appropriated that term for purposes of their own.

Robert Heinlein’s time traveler, Bob Wilson, revisits his past selves—conversing with them and modifying his own life story—and in his way the narrator of In Search of Lost Time, sometimes named Marcel, does that, too. Proust, or Marcel, has a suspicion about his existence, perhaps a suspicion of mortality: “that I was not situated somewhere outside of Time, but was subject to its laws, just like the people in novels who, for that reason, used to depress me when I read of their lives, down at Combray, in the fastness of my wicker chair.”

“Proust upsets the whole logic of narrative representation,” says Gérard Genette, one of the literary theorists who attempted to cope by creating a whole new field of study called narratology. A Russian critic and semioticist, Mikhail Bakhtin, devised the concept of “chronotope” (“time-space,” openly borrowed from Einsteinian spacetime) in the 1930s to express the inseparability of the two in literature: the mutual influence they exert upon each other. “Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible,” he wrote; “likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history.” The difference is that spacetime is just what it is, whereas chronotopes admit as many possibilities as our imaginations allow. One universe may be fatalistic, another may be free. In one, time is linear; in the next, time is a circle, with all our failures, all our discoveries doomed to be repeated. In one, a man retains his youthful beauty while his picture ages in the attic; in the next, our hero grows backward from senescence to infancy. One story may be ruled by machine time, the next by psychological time. Which time is true? All, or none?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Time Travel»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Time Travel» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Time Travel» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.