Lena tore out a soft piece from the middle. Ben stuck it into the hole and waited. There were no more drops.

“Let’s hope for the best,” he said, and climbed back into bed. Lena gave him his mug and snuggled against his shoulder.

“Listen, that image of a little boy in the phone booth—” Ben said.

“Sasha?”

“Yes. I’m positive I’ve seen it somewhere.”

“Where?”

“Wait, let me think.”

He put his mug down and covered his face with his hands. Then he dropped his hands and looked at Lena.

“I think I know where. I bought this graphic novel about five years ago. It was published somewhere in Europe. London, I think. It was about a Soviet summer camp. A mildly pornographic horror story. Some of the art was amazing, but overall I don’t think it was very good. I’m pretty sure there was the same crazy shit about that black sausage of yours. Only it was called purple sausage and it was drawn as a cock.”

Lena’s heart was thumping like crazy. Could it be that there was a book about her summer camp out there? A real, published book?

Lena sat up in bed and clutched the edge of the blanket: “I have to see it! Do you have it here?”

“I might. Leslie packed up most of my graphic novels, except for the ones I need for my class and a few famous ones. And since that one wasn’t famous and I never used it for my teaching, there is a very good chance that I have it here.”

“Look for it! Please, look for it!”

“Yes, sure.”

They climbed out of the bed, put on their clothes, and went over to the cold corner of the cabin where Ben had dumped the boxes.

There were hundreds of books, mostly old, yellowed, well worn, with greasy pages, but some of them new.

“What does it look like?” Lena asked. “Is it big? Small? Hardcover?”

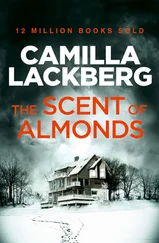

“I think it was softcover, but rather large. Dark cover.”

Lena had two fears. First, that they wouldn’t find the book at all. And second, that they’d find it but it wouldn’t have anything to do with her camp or her story. That this would be just some weird coincidence.

“Here it is!” Ben said, holding up an oversized album in a dark brown cover. He carried it back to the bed.

Lena felt a terrible surge of nausea. She wished now it wouldn’t have anything to do with her camp or her story. She was terrified of whatever they might find.

Ben plopped onto the bed with the book.

“Yep. Hands over the Blankets —just as I remembered. Okay. Now, who is the author? Simon Alexander. Does that ring a bell?”

Lena shook her head. No, she didn’t know anybody by that name. She walked to the bed and sat down on the edge next to Ben.

“How about his photo?”

A gloomy-looking man in his late twenties or early thirties. Glasses. Thinning hair.

She shook her head again. Perhaps this was only a coincidence.

“Let’s look at his bio,” Ben said.

“Simon Alexander grew up in Moscow, Russia. He lives in London and works at . . . Hands over the Blankets is his first book.”

London? Was this book that “amazing thing” that Sveta Kozlova wanted to show to her? And Inka? Inka mentioned that she’d met up with Sveta Kozlova.

The description claimed that this was one of the most striking debuts of recent years and one of the most “haunting stories of sexual oppression,” where “a melodrama of first innocent love unfurled through mad jealousy and escalated to a dizzying climax,” where it ended “in sabotage, shame, and despair,” but was somehow told with “delightful humor.”

“Should we read it?” Ben asked.

Lena took the book from him and opened it in her lap. On page 1 there was a whole-page drawing of a little boy caught masturbating. The caption read: “They would storm into our room at night and yell: ‘Hands over the blankets!’ ”

The drawing was pretty realistic—tiny limp penis squeezed in the child’s hands. There was horror in the child’s eyes.

Lena recognized those eyes.

“Sasha Simonov?”

Lena closed the book and peered into the author’s photo. She could now see some resemblance. Sasha who’d always wanted to become an artist. His full name was Alexander Simonov. He simply switched his last and first names to make his alias. How did he end up in London? But then so many people had left Russia, it was probably easier to meet some old acquaintance abroad. Anyway, none of it mattered.

“Yes, that was him. That’s not true, though,” Lena said.

“What’s not true?”

“We never yelled anything like that.”

“Well, perhaps, this was his artist’s imagination at work.”

Lena turned to the next page. The whole page looked like a tribute to the idyll of Sasha’s family life. His father was in the center as a framed portrait. Large and square, he looked nothing like Sasha. He was wearing a military uniform with huge golden stars on his shoulder straps.

“Is he supposed to be a general or something?” Ben asked.

“I don’t know. But I guess he must have been a big shot. I had no idea.”

Sasha’s mother was a pretty petite thing sitting in an armchair next to the portrait. Sasha, himself, was a tiny faceless figure by her feet. The family belongings took up the rest of the space in the drawing. There was a huge TV, a cabinet with gleaming porcelain, an enormous stereo system, and an opened fridge with a pineapple and a bunch of bananas as a centerpiece, and several jars on different shelves, each labeled CAVIAR.

“Yep, the dad must have been a big shot,” Lena said.

“We were a happy family. We owned things nobody’s even dreamed of,” the caption read.

The next frame featured the same room with the portrait, armchair, and fridge filled with caviar. But the mom was drawn tiptoeing out of the apartment with a suitcase, where a man in a hat was waiting for her, and the dad in the portrait looked forlorn and lost.

“They thought summer camp would be a nice distraction. Or perhaps they were too busy to deal with me,” the next caption said.

There was a ramshackle bus in the center going down the dusty road. Sasha was in the back of the bus. Looking out onto the road. Crying.

The next series of frames depicted the kids’ daily activities at the camp. Morning assembly. Meals. Playtime. Bathroom. All of these frames showed ugly screaming women and kids looking terrified.

“The days were filled with horrors, big and small.”

On the next page was a close-up of one of the horrors. A little boy, who looked like the masturbating boy from the first drawing, made some kind of a mess in the cafeteria, and the woman with huge boobs and teeth was yelling at him. And in the next frame the boy was throwing up. Supposedly from horror.

“As were the nights.”

The next page was done as a series of four frames. A boys’ bedroom in sinister moonlight in each of them. The boys lying in bed. Hands above the blankets. A woman sitting on the windowsill with speech bubbles coming off her face—apparently telling the kids a story.

“And then he took her to the woods.”

Sasha’s face stricken with horror.

“And then he tied her to the tree.”

Sasha’s face stricken with horror. A small bright yellow spot on his bed.

“And then he killed her.”

The yellow spot spreading over the bed.

“And then he ate her.”

Sasha’s bed turned into an enormous yellow puddle. He is drowning there.

“That wasn’t true!” Lena said. “Our stories weren’t that scary!”

The other kids in the drawings looked pretty scary as well. Most of them had murderous expressions. And the games that they played all appeared to be pretty violent.

Читать дальше