Strategic Legerdemain

The game of juggling roles and representations— the third defining flexian feature—helped the players build and reinforce these myths, not only with the media, but with governments and international institutions. Of course, such juggling was facilitated by the lack of information independent of the players. With information in the possession of the most involved players, and with little opportunity for independent verification until after the fact, if at all, their accounts could easily be taken at face value. This, of course, enhanced the players’ influence and authority, while demanding little accountability.

For the Chubais-Harvard players to maintain their leading positions and squelch potential opposition, they had to promote the myths with the media that mattered. Anders Åslund was one of their prominent storytellers. A former Swedish envoy to Russia whose connections to Chubais and associates went back to the late 1980s, Åslund worked with Sachs and Gaidar and served as a member of the boards of multiple Chubais-Harvard-run, foreign-aid-sponsored organizations. Those are but a few of his many links to the players. He was intimately involved on many sides and flexed his various roles to suit the situation. To name four: Chubais’s personal (unofficial) envoy (as he was understood to be by some Russian officials in Washington); a “private” citizen of Sweden who played a leading role in Swedish policy and aid toward Russia; a participant in high-level meetings at the U.S. Treasury and State Departments about U.S. and IMF policies; and a person engaged in business in Russia (and Ukraine, where he also operated). (While Åslund denies business activity in Russia, he had “significant” investments there, according to the Russian Interior Ministry’s Department of Organized Crime.) Yet, when writing for publication, Åslund always mentioned only a fifth role—that of a (presumably independent) analyst affiliated with Washington think tanks. (Flexians, of course, adopt the most prestigious and neutral of their various roles when in the public eye.) Writing frequently for the Washington Post , London’s Financial Times, Foreign Affairs , and other influential publications, Åslund was also among the most quoted analysts of the Russian economy by Western journalists. While presenting himself as a detached think-tanker, Åslund steadfastly promoted Chubais and the Reformers. But as their (unofficial) envoy, he can hardly be regarded as a disinterested analyst. 32

Åslund was by no means alone. His Chubais-Harvard teammates were equally adept at presenting the most appropriate of their roles to meet any given situation. To best serve their own objectives (though not necessarily those of the nations and efforts they supposedly represented), they donned all manner of government, political, business, NGO, and university hats, performing overlapping, shifting, or ambiguous roles to achieve their goals. The Chubais-Harvard players distinguished themselves, at least in the recent history of developed states, by their readiness and ability to exchange roles—even to the extent of representing a different nation from their own. Key players switched the side they represented back and forth depending upon their purposes. Such activity is not wholly new. But it can achieve more in today’s world, when “nonstate” actors standing in for states, and with exclusive access to official information, brand their activities as they like for an unsuspecting audience. 33

Take Jonathan Hay. In addition to being Harvard’s chief representative in Russia, with management authority over other U.S.-funded contractors, Hay was appointed by members of the Chubais Clan to, in essence, be a Russian. According to documents I obtained from officials of the Chamber of Accounts (Russia’s rough equivalent of the Government Accountability Office), Hay was given signature authority, empowering him to approve or veto some privatization decisions of the Russian state. Thus did Hay, an American citizen and consultant to a private entity, represent the Russian state. 34

In roles that overlapped and blurred, Hay represented Russia, the United States, his girlfriend Elizabeth Hebert’s company, and the business interests of himself and his associates. He could play these roles interchangeably or simultaneously, the sum of all of them becoming greater than any one by itself. He became, in effect, his own institution. No wonder higher-status Americans and Brits, whose titles and track records were weightier than Hay’s, deferred to him.

Such juggling is not inherently bad or unethical. It does, however, illustrate why flexians are so difficult to hold to account. For instance, when asked by U.S. authorities to explain his privatization or aid directives, Hay could legitimately argue that he had made those decisions as a Russian, not an American. His multiple roles afforded him an “out”—or at least wiggle room. For he could always claim to have been playing another role. While Hay’s multiple roles could be rationalized as efficient, they can hardly be judged to be immutably accountable to organizations, funders, or countries, let alone reflect clarity of loyalty, except, notably, to his fellow players. 35

Power of the Collective

Players like Åslund and Hay, who were so very adept at juggling their roles and representations, greatly compound their advantages when they work as part of a flex net. This allows them to create a resource pool , the third feature of flex nets, from which they can draw. By aggregating their various roles and financial resources, such players gain collective effectiveness.

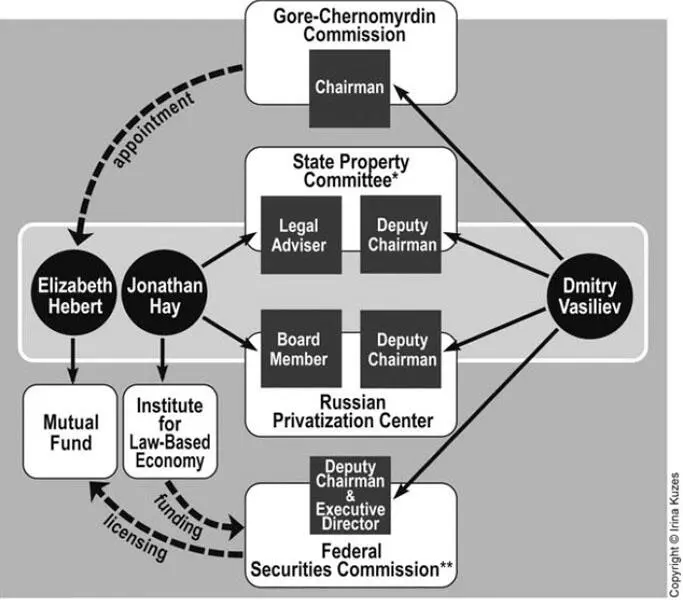

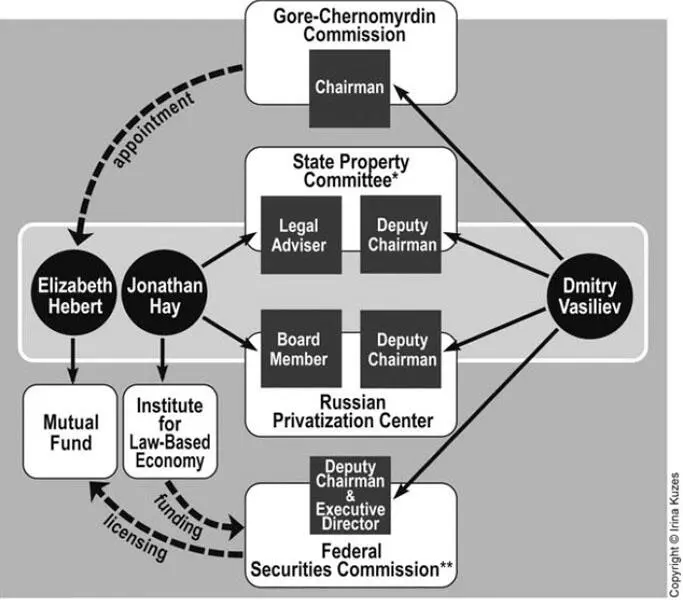

The Chubais-Harvard players engaged each other in a variety of venues, keeping each other apprised of valuable information, and making deals on behalf of each others’ spouses and associates. They became evermore intertwined. Take, for instance, just two individuals, Hay and Vasiliev. In addition to their ties to each other via the State Property Committee, the Russian Privatization Center, and the Federal Securities Committee (as detailed earlier), they enlisted each other in transactions to further their own purposes. For instance, Vasiliev fixed several matters for Elizabeth Hebert, arranging for her participation in the Gore-Chernomyrdin Commission’s Capital Markets Forum. More important, as head of the Federal Securities Commission, Vasiliev arranged for Hebert’s company, a little-known mutual fund, to be the first licensed fund in Russia—ahead of Credit Suisse First Boston (now Credit Suisse) and Pioneer First Voucher, both high-powered investment firms. This decision displeased the much larger and more established financial institutions. Vasiliev even put Hebert’s company in charge of an important Russian government fund (financed by the World Bank) that was set up to compensate victims of pyramid schemes that had defrauded many citizens. Vasiliev’s decision was taken not only without a competitive tender, it further disadvantaged the already disadvantaged victims. 36

CHUBAIS-HARVARD PLAYERS

Multiple Roles of Two Key Actors

(Early 1990s)

* The Russian acronym is the GKI.

** The Federal Securities Commission is also known by Americans as the “Russian SEC.”

This account of Hay’s and Vasiliev’s roles (illustrated above) conveys the connectedness of just two players. Imagining up to a dozen players—all strategically placed and interlinked like these—gives a glimpse of how the Chubais-Harvard flex net was afforded wide-ranging influence by pooling roles. The greater the positioning in roles that matter and the more the potential for the roles to influence each other when the players enact them, the more influence the players can wield.

Читать дальше