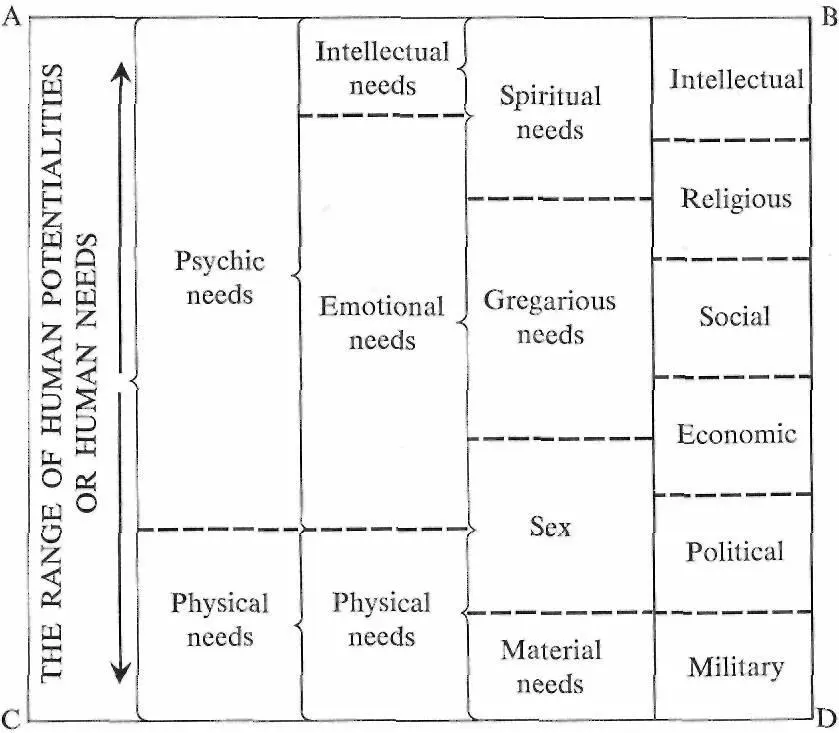

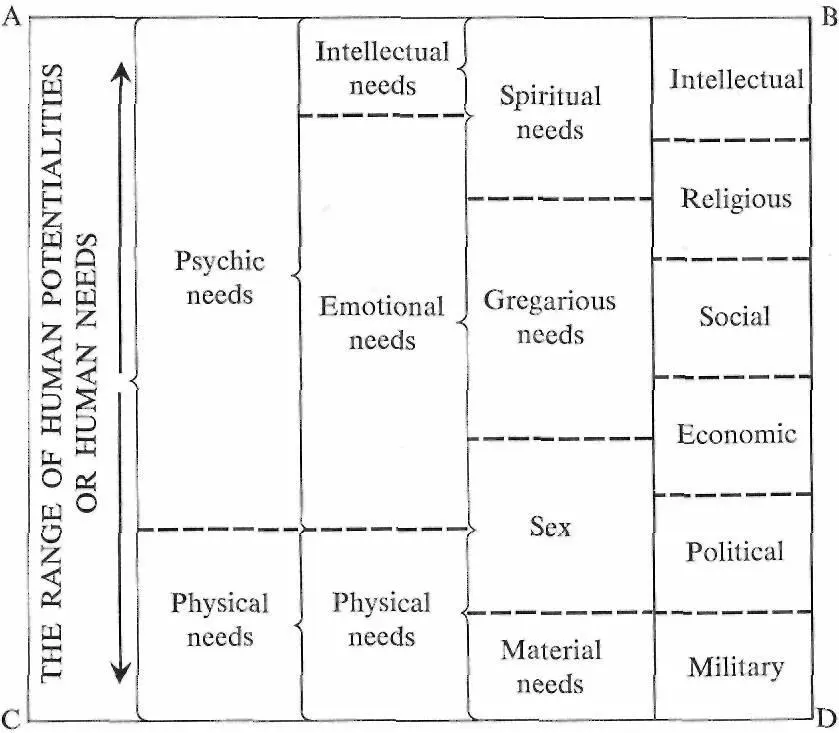

We have said that the individual's reactions in behavior, in feeling, and in thought (what we call his personality) are largely determined by his cultural environment. At the same time, his personality is part of the cultural environment of those people whom he meets. And, as already said, only by such relationships is his personality developed from his human nature. All this makes a human being so different from a turtle that nothing very relevant to human behavior can be learned from the study of turtle behavior. With the turtle we are dealing with a twofold situation: the turtle and his environment. With the human being we are dealing with a threefold situation: the human being surrounded by his culture and both together surrounded by the natural environment—and by other cultures. Where a turtle lays dozens of eggs and hopes that some turtles from those eggs can be carried to maturity by obedience to fairly rigid instincts, the human has almost no rigid instincts, and adapts his personality to his culture. The culture in turn must adapt itself to the natural environment. Thus, if the natural environment changes, the turtle must change his nature, while man merely changes his culture (and thus his personality). But this beautifully flexible relationship requires such a long period of training and learning during which human nature becomes a human personality and the individual becomes able to care for himself, that humans are dependent upon their parents for many years. Accordingly, humans have few offspring, and each offspring is very valuable, since the survival of the species does not depend (as with turtles) on the more or less accidental survival of a very few out of the many reproduced, but depends instead on the ability to bring up almost all who were born and to train them so that they can take care of themselves, have the intelligence to modify their culture (including their personalities) when it becomes necessary to adapt to the environment, and at the same time develop the capacity to use the freedom to change their behavior (which this whole situation assumes) in such a way that it will be beneficial to themselves and to the group on which they depend for the continuation of their culture. All this leads us to certain tentative assumptions about human nature, about the nature of culture, and about the nature of human society. In regard to human nature, it would seem that we have to deal with two things: (a) a wide range of potentiality and (b) a drive to make these potentialities actual. The range of these potentialities seems to run a full gamut from the most concrete and material activities, such as eating or moving about, through a broad belt of emotional and social activities to a fairly broad range of spiritual and intellectual activities. It would be rash to say that this range of potentialities has very specific qualities or needs in it or that there are any intrinsic dividing lines separating one potentiality from another. A study of human personalities and human cultures would seem to indicate that these potentialities blur into one another, that each person has opposing (and even incompatible) extremes of each potential quality, and that there can be a good deal of substituting of one potential quality for another as these qualities develop into actual characteristics. Any divisions we may make in this gamut of human potentialities are probably arbitrary and imaginary. We might divide the range into two: physical and spiritual; or into three: physical, emotional, and intellectual; or into four (a) material needs, such as food, clothing, shelter; (b) sex; (c) gregarious needs, such as companionship; and (d) psychic needs, such as a world outlook, psychological security, or the desire to know the "meaning" of things. We could, indeed, divide this gamut into forty or into four hundred divisions or levels, since the reality with which our words seek to deal is a subtle, continuous, and flexible range quite beyond our ability to grasp clearly or fully. This range of human potentialities will sometimes be divided in this book, for purposes of historical analysis, into six levels, as follows: (1) military, (2) political, (3) economic, (4) social, (5) religious, (6) intellectual , although this division will always be made with the full realization that it could, with good justification, be made otherwise as five, seven, sixty, or six hundred levels.

This range of human potentialities is also the range of human needs because of man's vital drive that impels him to seek to realize his potentialities. This drive is even more mysterious than the potentialities it seeks to realize. Throughout history men have given various names to this drive, and there have been endless disputes about its names and about its extent and nature. The Classical Greeks, like Aristotle, sought to ignore it by merely assuming that everything had a purpose and that everything by its very nature sought to achieve its purpose. This is generally known as a teleological explanation (from the Greek word teleos, meaning purpose or goal). In the Christian Middle Ages this teleological approach was somewhat modified by the belief that, while everything had a purpose, things were drawn to seek to fulfill these purposes by the love of God. About the year 1600 men began to place this drive inside men (driving them on) rather than outside (drawing them on) as before 1600. Spinoza about 1670 called this drive the "soul." About 1818 Schopenhauer called it "will." About 1890 Bergson called it "the vital urge," while at the same time Freud called it "sex." Throughout this later period many natural scientists called it "energy." Without getting into any controversy about the merits of these various terms, we can agree with them all that there does seem to be some force driving men to seek to realize their potentialities. Before going further to examine how these efforts produce both culture and societies, let us try to sum up our conclusions regarding the divisibility of the range of human potentialities by the following diagram in which the distance between the line AB and the line CD represents this range.

The various columns represent various ways in which it might be divided. This range as a whole we shall call "the dimension of abstraction":

When these potentialities of human nature are realized, they become the characteristics of human personality. This is very helpful, for we cannot directly observe or study human nature, and are compelled to make assumptions as to what it must be like from our studies of human personality. Since the characteristics of human personality emerge from the potentialities of human nature as a result of experience and training, and since each person's experience and training are different, each personality is different. At the same time, since each person in the same society is brought up in the same culture and thus tends to have similar experiences and similar training, most of the persons in a society tend to have a basic personality pattern, with similar general characteristics either emphasized or subdued.

Not only is human personality formed by the social environment; the social environment (or culture) is largely made up of the personalities it has created. In this way culture is passed down from generation to generation, always somewhat changed but always largely the same. From this point of view culture is known as the social heritage, passing on from generation to generation by teaching and learning, most of it unconscious.

When a child is first trying to walk, he may fall without actually hurting himself. What happens in the next few moments may contribute considerably to the formation of his future personality. If an adult swoops down on him, full of sympathetic sounds and commiseration, he may decide that he is hurt and begin to cry. This could easily become one of the earliest steps toward forming a personality that reacts to the unexpected with self-pity. On the other hand, such a fall might lead some neighboring adult to say: "Get up, Jimmy, and try again. You must be more careful and watch where you are going." This could easily be an early step toward self-responsibility and self-reliance. Frequently, after such a fall, the child, if ignored, will be frustrated and resentful. Struggling to his feet, he may strike out at the nearest person or at some inanimate object. Again the reactions of surrounding adults depend upon the personality patterns of the culture, and serve to mold the developing personality of the child. There are societies where a frustrated child who strikes at an innocent bystander might be admired: "Look at that spirit; isn't he the little man!" This serves to encourage the development of a culture based on personalities of irrational aggressions. If, on the other hand, a child who displays an early response of aggression to frustration is immediately stopped, has his hands slapped to discourage such a reaction, and is sternly warned: "You fell because you were not careful and did not watch what you were doing. Mrs. Jones had nothing to do with your fall, so don't you dare strike at her … ," in such a case the child's personality will be turned from aggression to self-responsibility.

Читать дальше