Every economic system has to be regulated. That is, somehow, decisions must be made as to what is produced, how much of it, and who gets it. In the early Middle Ages and again in the late nineteenth century, the European system of management was an unregulated, automatic one. That is, no centralized decision making occurred in either. But the two were entirely dissimilar in the ways that this came about. In the medieval system, economic regulation was automatic through medieval custom: what was produced, how much, and who got it were established on the basis of what had been done at an earlier date. Custom ruled.

In the nineteenth century, once again, Europe had an automatic management of economic life, but now it was a dynamic economic system, not the static one of the earlier Middle Ages, and, as a dynamic system, it could not be regulated by custom. Instead, it was regulated by the market. The market is a place where buyers and sellers come together to exchange their goods. In an automatic laissez-faire market numerous sellers compete with each other, thus forcing prices downward, while simultaneously numerous buyers compete with each other, thus forcing prices upward, and, finally, during all this, buyers "higgle" with sellers. As a consequence of these three forces operating in the market, a price is reached at which goods are exchanged for money in terms that will clear the market of both.

Such a market mechanism is fully capable, as we all know, of determining, without centralized control, what will be produced, how much will be made, and who will get it. But no laissez-faire system can do this unless a market exists, and no such market can exist unless both transportation and communications are so highly developed and so free that people know what is going on and both goods and money are free to move where each is more valuable. Neither transportation nor communications were adequate to this purpose when the customary system of the static medieval economy began to break down from the introduction of dynamic economic influences about the year 1000. Thus there was no market in the year 1000, and there was still no market, although a myriad of small markets, in 1700. These small markets existed from the inadequacy of both transportation and communication, and were "small" in the sense that the numbers of buyers and the numbers of sellers in each market were too small to prevent monopolistic or oligopolistic prices and to achieve competitive prices. To prevent this and to protect the consumer from exploitation, municipal mercantilism grew up and dominated economic regulation during the period 1200-1500 approximately.

As improvements in transportation and communications appeared in the period of medieval expansion, there was a tendency for the numerous small markets regulated by municipal mercantilism to flow together to create fewer and larger markets. These larger markets, drawing from areas larger than the areas of municipal control and similarly supplying goods to larger areas, could not be controlled by municipal authorities. Still, these authorities continued to attempt to do what was technically beyond their powers to do. These efforts, aiming at the defense of established vested interests rather than at the protection of consumers as originally intended, are part of the institutionalized structure of the first Age of Conflict.

As a consequence of the inability of municipal authorities to regulate the newer, larger markets created by improved transportation and communications, this task was taken over by the emerging dynastic monarchies. We have already shown how changes in weapons, political organization, and political ideology had created these newer political structures with power to regulate economic life over larger areas. This newer economic regulation by dynastic monarchies is known as state mercantilism. It aimed to protect traders rather than consumers or producers. Much of the expansion of the second period of expansion arose from its efforts.

By the eighteenth century, state mercantilism had become in its turn a structure of vested interests serving to hamper economic life rather than to help it. This was as true of traders as it was of consumers and producers. This shift of state mercantilism from an instrument to an institution was based on two chief features. On one hand the organization was no longer used for an economic purpose but had become an end in itself with largely political purposes. It was used to increase state power rather than for economic life. On the other hand, by the late eighteenth century, transportation and communication were again beginning to improve so rapidly that continental and even world markets were coming into existence. These were, of course, much wider than the areas of power of the dynastic monarchies and, accordingly, could not be controlled by them. The continued efforts of governments to exercise such control in the portions of markets that fell in their respective power areas merely served to create restrictions on economic life and hampered production, exchange, and consumption alike. This situation was shown by Adam Smith in his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Clearly markets were now large enough to be regulated by supply and demand, by competition and higgling, and any movement to allow this would be economically progressive. From this point of view, also, the Napoleonic Wars represented a struggle between an older and a younger system.

Thus from four points of view concerned with finance, agriculture, manufacturing, and economic regulation, the political struggles between England and France in the Napoleonic period reflect a contest between the future and the past. There are, of course, numerous other factors involved in this contrast. Some of these will be mentioned in the next section, but these four should be sufficient to show that Napoleon represented an outmoded system and that he was the last phase of a fairly typical Age of Conflict.

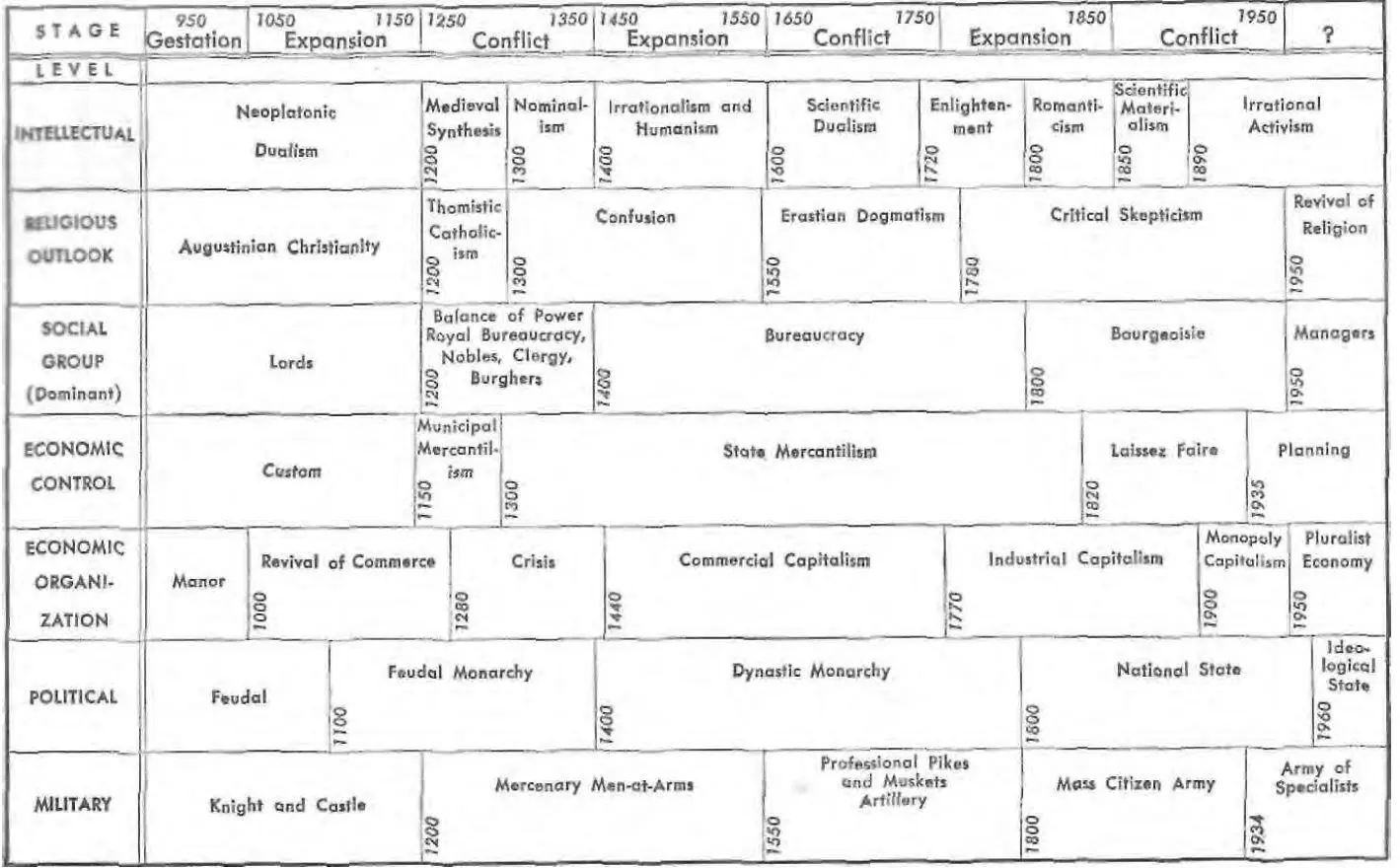

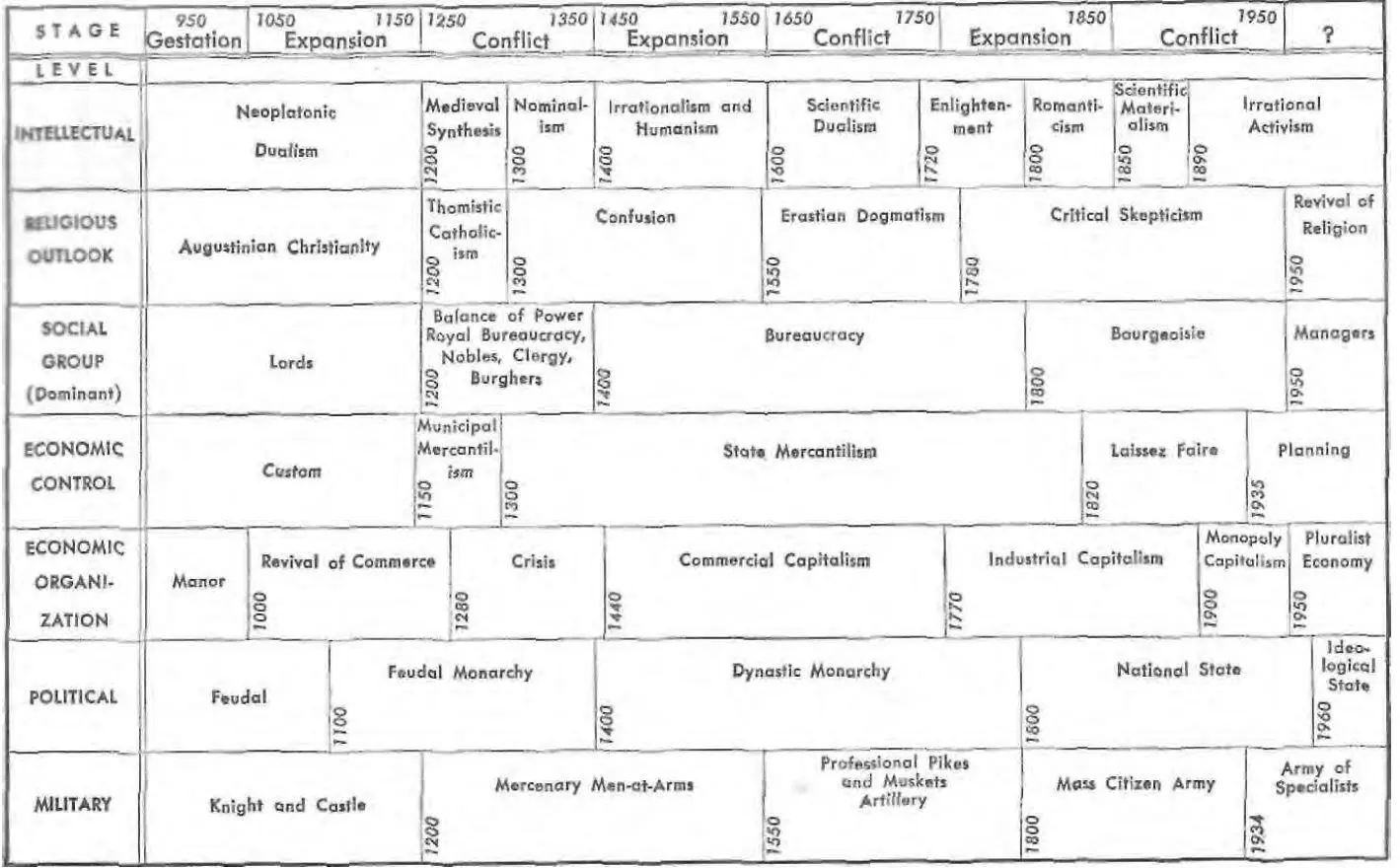

The other marks of such an Age of Conflict, with one notable exception, are fairly obvious or have been mentioned already. The exception is in intellectual history, where an Age of Conflict usually is a period of irrationality. This is, of course, not a term that could be applied to the eighteenth century where the more usual label (at least for the generation 1730-90) is "Enlightenment." This discrepancy is but one indication of a situation that is far too complex to be discussed here; namely, that the periodization of intellectual history is quite different from the periodization of other aspects of society. In these other aspects we can distinguish five successive stages on each level over the period from A.D. 950 into the future, but on the intellectual level, as shown in the chart (page 389), we have at least nine stages over the same time. To some extent this can be explained by cultural lag, but there are other influences quite as significant, including the much weaker degree of integration between one theory and another, even at the same time, or between a theory and any other aspect of the society, than exists between the more concrete aspects of culture.

At any period, it is possible for a thinker either to accept a theory which is morphologically compatible with his age or to reject it. In such cases the ideology of the age must be sought in the generally unstated assumptions made both by conformists and nonconformists. In the eighteenth century the Enlightenment was nonconformist to the other levels of the society, and this is, indeed, one of the chief causes of the French Revolution. The rational, orderly, organized qualities of the Enlightenment were quite incompatible with the irrational, disorderly, and disorganized society of the day, and thus gave rise to tensions that, reinforced from other directions, provided the energy motivating the French Revolution.

Читать дальше