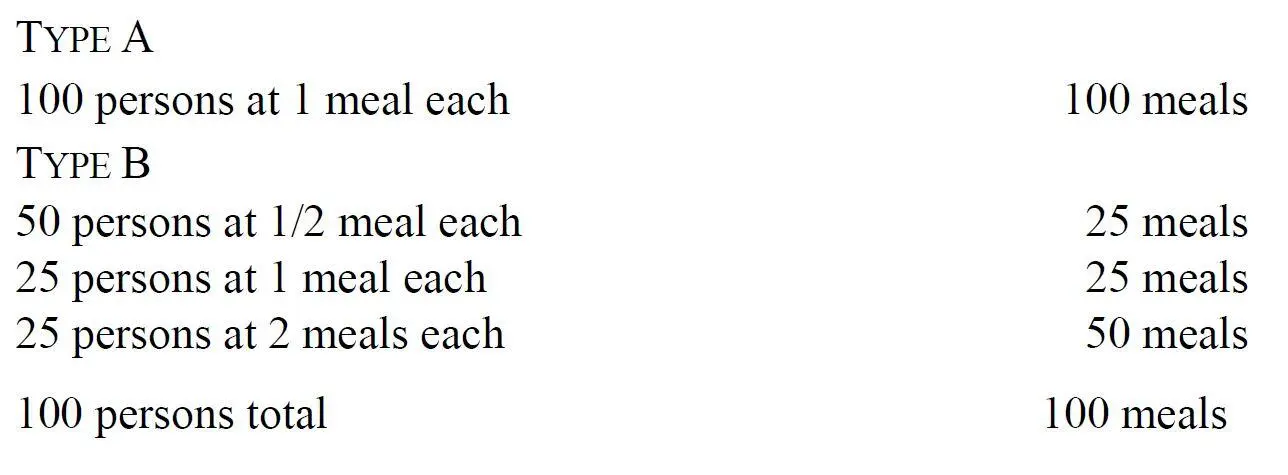

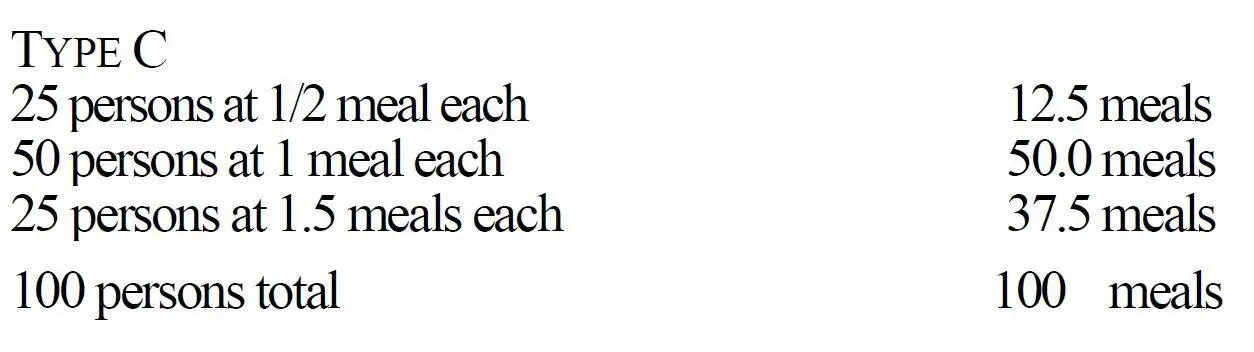

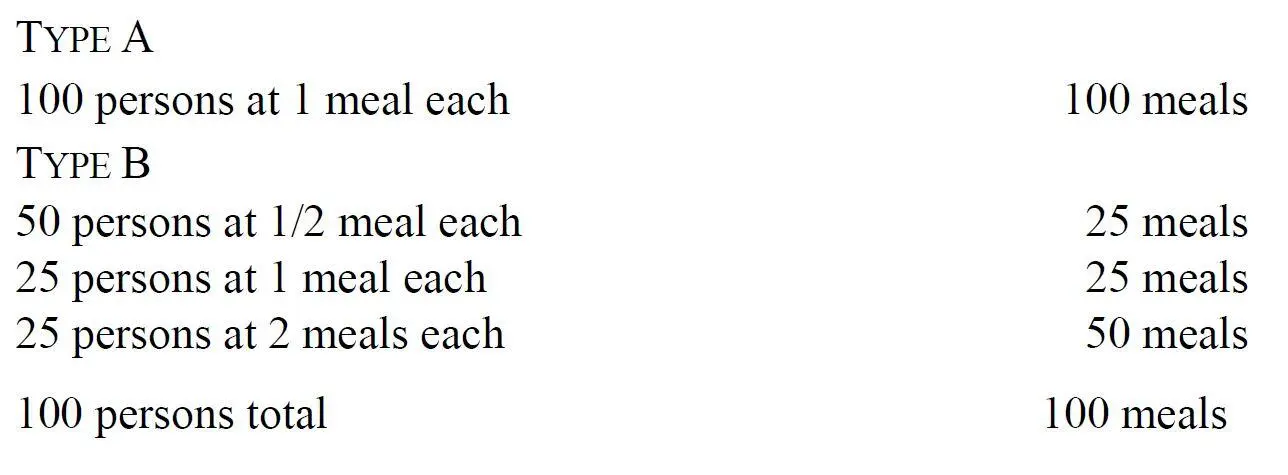

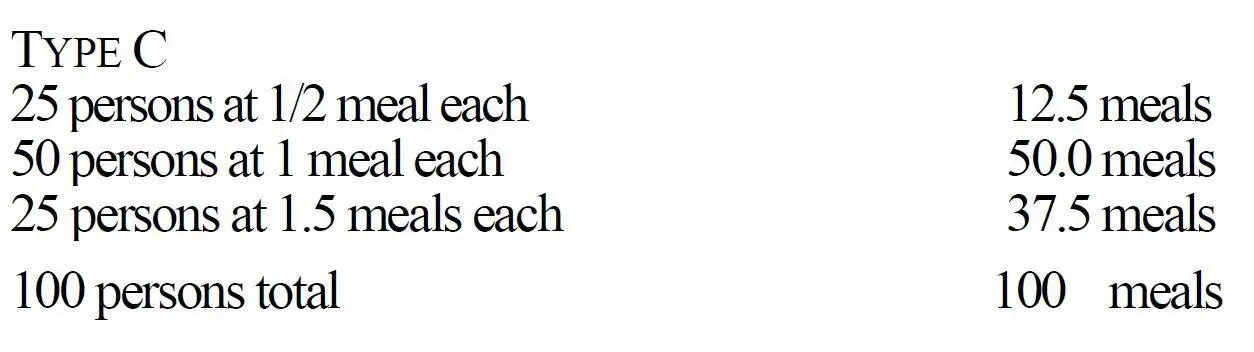

With Type A distribution there can be no increase in output even if someone thinks of a new invention, since no one would have leisure to make it. With Type B distribution there may be an increase in output but only if someone thinks of a new invention and if the surplus of meals controlled by the twenty-five richest persons is redistributed to the poorer persons as payment for these poorer ones making the new invention. This would give a third type of income distribution if the surplus was invested in the way mentioned. Thus:

Every kind of material progress and many kinds of nonmaterial progress depend upon the three factors we have mentioned. This is as true of parasitic societies as it is of productive societies. Let us imagine a solitary savage who lives by hunting and who, by throwing rocks at game from dawn to dusk, averages one rabbit a day. Let us further imagine that this diet of one rabbit a day is just enough to keep him alive until the next day. In such a situation this lonely hunter could not make a bow and arrow, even if he could invent it in his mind, because to make a bow and arrow would take, let us say, ten days' work. Thus this savage has an incentive to invent, even has the necessary invention, but he has no surplus and cannot improve his position. Then let us assume that he throws a rock one day and kills a deer large enough to keep him alive for twelve days. He now has both invention (in his mind) and surplus (the deer). He may live from the deer for twelve days in idleness, or he may use his leisure from hunting to make the bow and arrow he has conceived. In the former case he will be no better off, and may be worse off because of loss of skill in rock throwing as a result of such leisure. In the latter case, on the contrary, his surplus (the deer) is transformed into a bow and arrow by investment, and at the end of ten days he has a new weapon that raises his ability to kill rabbits from an average of one a day to, say, an average of three a day. Of these three he can consume one a day himself, as previously, and support two other savages with the two other rabbits he kills each day. In return for such support, these two could be required to build a hut, to cure rabbit skins, to make additional arrows, and so forth. In this way the new capital equipment, the bow and arrow, has made it possible to raise the standards of living of all three.

It is by some such process as this, but much more elaborate and complex, that civilizations grow, thrive, and expand. Every civilization must be organized in such a way that it has invention, capital accumulation, and investment. Loosely speaking, the term "instrument of expansion" might be applied to the organization for capital accumulation alone, although, strictly speaking, this organization should be called the surplus-creating instrument. This surplus-creating instrument is the essential element in any civilization, although, of course, there will be no expansion unless the two other elements (invention and investment) are also present. However, the surplus-creating instrument, by controlling the surplus and thus the disposition of it, will also control investment and will, thus, have at least an indirect influence on the incentive to invent. This surplus-creating instrument does not have to be an economic organization. In fact, it can be any kind of organization, military, political, social, religious, and so forth. In Mesopotamian civilization it was a religious organization, the Sumerian priesthood to which all members of the society paid tribute. In Egyptian, Andean and, probably, Minoan civilizations it was a political organization, a state that created surpluses by a process of taxation or tribute collection. In Classical civilization it was a kind of social organization, slavery, that allowed one class of society, the slaveowners, to claim most of the production of another class in society, the slaves. In the early part of Western civilization, it was a military organization, feudalism, that allowed a small portion of the society, the fighting men or lords, to collect economic goods from the majority of society, the serfs, as a kind of payment for providing political protection for these serfs. In the later period of Western civilization, the surplus-creating instrument was an economic organization (the price-profit system, or capitalism, if you wish) that permitted entrepreneurs who organized the factors of production to obtain from society in return for the goods produced by this organization a surplus (called profit) beyond what these factors of production had cost these entrepreneurs.

Like all instruments, an instrument of expansion in the course of time becomes an institution and the rate of expansion slows down. This process is the same as the institutionalization of any instrument, but appears specifically as a breakdown of one of the three necessary elements of expansion. The one that usually breaks down is the third— application of surplus to new ways of doing things. In modern terms we say that the rate of investment decreases. If this decrease is not made up by reform or circumvention, the two other elements (invention and accumulation of surplus) also begin to break down. This decrease in the rate of investment occurs for many reasons, of which the chief one is that the social group controlling the surplus ceases to apply it to new ways of doing things because they have a vested interest in the old ways of doing things. They have no desire to change a society in which they are the supreme group. Moreover, by a natural and unconscious self-indulgence, they begin to apply the surplus they control to nonproductive but ego-satisfying purposes such as ostentatious display, competition for social honors or prestige, construction of elaborate residences, monuments, or other structures, and other expenditures which may distribute the surpluses to consumption but do not provide more effective methods of production.

When the instrument of expansion in a civilization becomes an institution, tension increases. In this case we call this "tension of evolution." The society as a whole has become adapted to expansion; the mass of the population expect and desire it. A society that has an instrument of expansion expands for generations, even for centuries. People's minds become adjusted to expansion. If they are not "better off" each year than they were the previous year, or if they cannot give their children more than they themselves started with, they became disappointed, restless, and perhaps bitter. At the same time the society itself, after generations of expansion, is organized for expansion and undergoes acute stresses if expansion slows up.

The nature of these organizational stresses and tensions arising from a decrease in the rate of a society's expansion can be seen most clearly in contemporary Western civilization. In this society the economic system produces three kinds of goods: (a) consumers' goods and services, (b) capital goods, which cannot be consumed but which can be used to make consumers' goods, and (c) government goods and services, including armaments. In producing each kind of goods, the factors of production, such as land, labor, materials, capital, managerial skills, entrepreneurial enterprise, legal fees, distribution costs, and so forth, must be used and paid for. These costs, including profits for entrepreneurs, have a double aspect. On the one side they represent the costs of producing the goods, and thus determine the final selling price of the goods; this must be sufficiently high to cover these costs. But, on the other hand, these costs represent the incomes of those who receive them and thus represent the purchasing power available to buy the goods offered for sale. If we look, for a moment, only at the flow of consumers' goods, we see that this flow of goods is offered for sale at a price that, by just covering the costs of the goods, is just equivalent to the purchasing power distributed to the economic community as incomes available for buying these goods. But, of course, some incomes are saved. These savings reduce the flow of purchasing power below the level of the flow of consumers' goods at prices sufficient to cover costs of these goods. Thus there is not sufficient purchasing power available to buy the goods being offered at the price being asked, and either goods must go unsold or prices must fall, unless the money which was held back as savings appears in the market as purchasing power for consumers' goods. Traditionally, this reappearance of savings as purchasing power in the market occurred through investment— that is, as expenditures for the factors of production to be used to make capital goods. This process provided the purchasing power needed to permit the flow of consumers' goods to go to consumers because investment distributed rent, salaries, wages, interest, profits, and such to the community to form incomes and thus available purchasing power but did not demand purchasing power from the economic community because the producers' goods created by these expenditures were not offered for sale to consumers, as consumers goods were, but, if sold at all, were merely exchanged for the savings of investors. This whole relationship means that our modern economic system cannot produce and consume what it produces unless it also invests (that is, expands).

Читать дальше