World War I provides a great case study in these principles. Its origins are complex and contentious, so we limit ourselves to describing the chain of events. The war started as a dispute between Austria and Serbia after Serbian nationalists murdered the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in June 1914. When Austria threatened war, Serbia’s ally, Russia, became involved. This activated Germany’s alliance with Austria. Given that war with Russia also meant war with her ally, France, the Germans launched a rapid invasion of France in the hope of quickly defeating it, as they had in 1871. The German invasion of France went through Belgium, and, since the British had pledged to protect Belgium’s neutrality, this brought Britain in on the side of the allies.

A tangled web! Although many nations were involved, the war was basically a struggle between the central powers of Austria and Germany and the allied powers of France, Russia, and Britain. After a dynamic beginning—the war was famously supposed to be over by Christmas—the conflict stagnated and devolved into trench warfare, particularly on the Western Front. Russia dropped out of the war in late 1917, after the Bolshevik Revolution. Doing so cost it enormous amounts of its Western territory, but the political genius of Lenin knew it was better to preserve resources to pay supporters than it was to carry on fighting. In late 1917, the United States entered the war on the allied side.7 Allied victory was sealed with an armistice signed on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918.

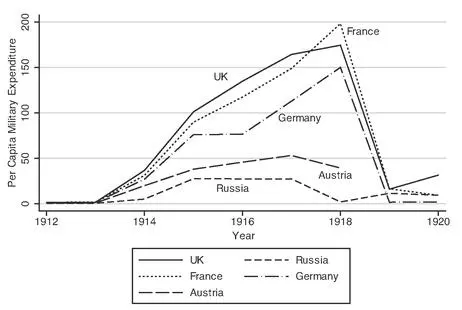

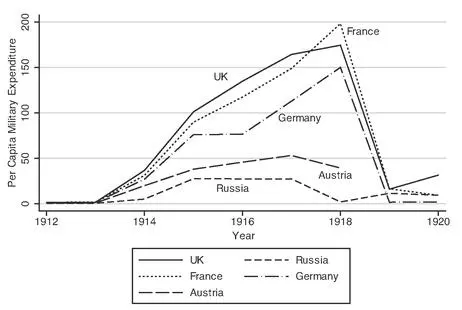

Figure 9.1 plots the military expenditures of the primary combatants. 8 On a per capita basis, Russia spent less than the others. It was both massive and poor. Of these nations only Britain and France were democratic. After the war started in 1914, all combatants ramped up their military spending. However, after 1915, the autocratic nations didn’t increase their effort much and their expenditures plateaued as the war dragged on. German spending does increase again in 1917 as it becomes clear that defeat will mean the replacement of the German government. In contrast to the meager efforts by autocracies like Austria and Russia, the democracies continue to increase expenditure until victory was achieved.

FIGURE 9.1 Military Expenditures in World War I

Sun Tzu’s advice to his king predicts the behavior of autocrats in World War I: they didn’t make an extraordinary effort to win. The effort by the democratic powers in that same war equally foreshadowed what Caspar Weinberger and so many other American advisers have said to their president: if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.

When it comes to fighting wars, institutions matter at least as much as the balance of power. The willingness of democracies to try harder goes a long way to explaining why seemingly weaker democracies often overcome seemingly stronger autocracies. The United States was once a weak nation. And yet, in the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) it defeated the much larger, better-trained, and highly favored Mexican army. The miniscule Republic of Venice survived for over a thousand years until it was finally defeated by Napoleon in 1797. Despite its small size and limited resources it fought above its weight class throughout the Middle Ages. It played a crucial role in the Fourth Crusade that led to the sacking of Constantinople, in which Venice captured the lion’s share of the Byzantine Empire’s wealth. The smaller, but more democratic government of Bismarck’s Prussia defeated the larger—widely favored—Austrian monarchy in the Seven Weeks War in 1866. Prussia then went on to defeat Louis Napoleon’s monarchical France in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War. And as we have seen, tiny Israel has repeatedly beaten its larger neighbors. History is full of democratic Davids beating autocratic Goliaths.

Fighting for Survival

Autocrats and democrats, at one level, fight over the exact same thing: staying in power. At another level, they are motivated to fight over different things. Democrats more often than autocrats fight when all other means of gaining policy concessions from foreign foes fail. In contrast, autocrats are more likely to fight casually, in the pursuit of land, slaves, and treasure.

This has important implications. As Sun Tzu suggested, autocrats are likely to grab what they can and return home. On the other hand, democrats fight where they have policy concerns, be these close to home, or, as can be the case, in far-flung lands. Further, once they have won, democrats are likely to hang around to enforce the policy settlement. Frequently this can mean deposing vanquished rivals and imposing puppet regimes that will do their policy bidding.9

Thinking back to our discussion of foreign aid, we can see that war for democrats is just another way of achieving the goals for which foreign aid would otherwise be used. Foreign aid buys policy concessions; war imposes them. Either way, this also means that democrats, eager as they are to deliver desired policies to the folks back home, would much prefer to impose a compliant dictator (surely with some bogus trappings of democracy like elections that ensure the outcome desired by the democrat) than take their chances on the policies adopted by a democrat who must answer to her own domestic constituents.

The idea that democrats and autocrats fight for their own political survival may seem awfully cynical at best and downright offensive at worst. Nevertheless we believe the evidence also shows this is the way the world of politics, large and small, actually works. A look at the First Gulf War will validate all of our suspicions.

Before 1990, relations between Iraq and Kuwait had long been fractious. Iraq claimed that Kuwait, with its efficient modern oil export industry, had been pumping oil from under Iraq’s territory. On numerous occasions it had demanded compensation and threatened to invade. After misreading confused signals from US president George H. W. Bush (on previous occasions the United States had deployed a naval fleet to the region in response to Iraqi threats but had also told Iraq’s government that what it did in Kuwait was of no concern to the United States), Saddam Hussein’s forces invaded and occupied Kuwait in August 1990. His goal was to exploit its oil wealth for the benefit of himself and his cronies—fairly typical for an autocrat at war. However, despite initially confused signals, the United States did not look the other way: President Bush organized an international coalition, and in January 1991 launched Operation Desert Storm to displace Iraqi forces.

The goals and conduct of each side in the First Gulf War differed greatly. In contrast to Hussein’s motives, President Bush did not attempt to grab oil wealth to enrich cronies. Rather, the goal was to promote stability in the Middle East and restore the reliable, undisrupted flow of oil. Protestors against the war would chant “no blood for oil.” It would be naïve to argue that energy policy was not a major, if not the major, determinant of US policy in the Middle East, but it was not an exchange of soldiers’ lives for oil wealth. The objective was to protect the flow of oil, which is the energy running the machines of the world’s economy. Economic stability, not private gain, was the goal of the coalition. To be sure, soldiers from the United States and other coalition members died, although in very small numbers. Of the 956,600 coalition troops in Iraq, the total number of casualties was 358, of which nearly half were killed in noncombat accidents. In contrast, Iraq experienced tens of thousands of casualties. These coalition deaths brought concessions from Saddam Hussein, not booty.

Читать дальше