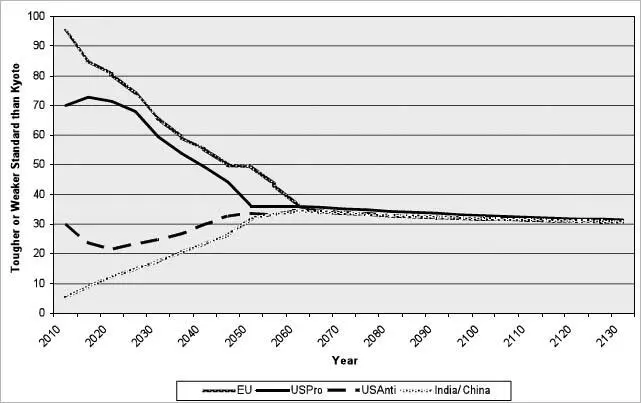

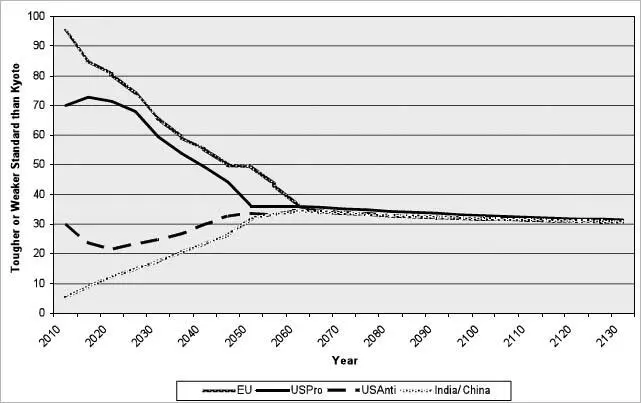

FIG. 11.3. What Will the Biggest Polluters Do About Greenhouse Gas Emissions?

Although the Kyoto Protocol was agreed to in December 1997, it did not take effect until February 2005. That is rather a long time for moving from agreement to presumed action on a matter of long-term global survival. Of the 175 countries, including 35 developed economies, that ratified the agreement, 137 don’t have to do anything except monitor and report on their greenhouse emissions. Counted among those 137 are China, India, and Brazil. With their growing economies and their large populations, these countries are among the world’s great greenhouse gas emitters. They won the battle in the negotiations that led to the Kyoto Protocol. They preserved their right to continue to pollute with no punishment for failing to do otherwise. That’s what cheap talk is all about. How about Japan, one of the world’s big economies that signed on to Kyoto? Remember, Japan’s target is a 6 percent reduction from its 1990 emissions. The Japanese government has stated that it cannot meet its emission reduction target. Britain, while making progress on some dimensions, seems incapable of meeting its pledged reduction in carbon dioxide emissions from its 1990 level by 2010. The picture isn’t pretty.

To be sure, several European Union states seem to be on track, and Russia does too, but then outside the oil sector the Russian economy has not done that well, and the Russians are only required not to increase emissions. One sure way to reduce carbon dioxide emissions is to have the economy slow down. Of course, that raises difficult political problems because people tend to vote against parties that produce poor economic performance. That could be a problem in the European Union. It’s not likely to be an issue in Russia, where democracy seems to be a victim of increased oil prices. (A global economic crash, however, will bring the price of oil down, and that could jeopardize Russia’s march back to autocracy.)

Anyway, what all of this amounts to is a record of cheap promises. It is easy to get governments to sign on to deals that have no teeth, no clear way to keep track of violators and to punish them. Kyoto relies heavily on self-reporting, self-policing, and goodwill. That’s no way to make a global arrangement that gets its signatories to make the sacrifices needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

If I sound downbeat, I am sorry. Actually, I am most optimistic for the future. My optimism, however, is despite—yup, despite —agreements like the ones struck in Bali or Kyoto or Copenhagen. These will be forgotten in the twinkling of an eye. They will hardly make a dent in global warming; they could even hurt by delaying serious changes. Roadmaps like the one set out at Bali make us feel good about ourselves because we did something. We looked out for future generations, we promised to do good—or did we? Unlike the pope and Holy Roman Emperor who signed on to Worms, universal schemes do not put big change into motion. Their all-inclusiveness ensures that they reflect the concerns of the lowest, not the highest, common denominator.

Deals like Bali and Kyoto include just about every country in the world. Such agreements suffer from the same wrong incentives and weak commitments as Arthur Andersen’s management did in auditing Enron. To get everyone to agree to something potentially costly, the something they actually agree to must be neither very demanding nor very costly. If it is, many will refuse to join because for them the costs are greater than the benefits, or else they will join while free-riding on the costs paid by a few who were willing to bear them. That is akin to the tragedy of the commons. We all promise to protect what we hold in common—such as the earth—and then some of us cheat on the sly to enrich ourselves, figuring our little bit of cheating doesn’t do any real harm. (Remember, defecting is the dominant strategy in the prisoner’s dilemma.)

To get people to sign a universal agreement and not cheat, the deal must not ask them to change their behavior much from whatever they are already doing, whether that is cleaning up their neighborhood or making it dirtier. It is a race to the bottom, to the lowest common denominator. More demanding agreements weed out prospective members or encourage lies. Kyoto’s demands weeded out the United States, ensuring that it could not succeed. Maybe that is what those who signed on—or at least some of them—were hoping for. They can look good and then not deliver, because after all it wouldn’t be fair for them to cut back when the biggest polluter, the USA, does not.

When an agreement is demanding, lots of signatories cheat; when it isn’t demanding, there is lots of compliance with what little is asked for, but then there is also little if any beneficial effect. Sacrificing self-interest for the greater good just doesn’t happen very often. Governments don’t throw themselves on hand grenades. 4

It really isn’t easy being green, just as Kermit the Frog has been telling us for years. Who will monitor green cheaters? The answer: interest groups, not governments; and interest groups are rarely a match for governments. Who will punish the cheaters? The answer: practically no one. The cheaters-to-be were among the rule makers when they agreed to the universal protocol. Cheating is an equilibrium strategy for many polluters, a strategy backed by the good faith and credit of their governments. Why will governments back cheaters? The answer: incentives, incentives, incentives!

Who has what incentives? There is a natural division between the rich countries whose prosperity does not depend so much on toasting our planet and the poor countries who really have no affordable alternative (yet) to fossil fuels and carbon emissions. They have an incentive to do whatever it takes to improve the quality of life of the people they govern.

The rich have an incentive to encourage the fast-growing poor to be greener, but the fast-growing poor have little incentive to listen as long as they are still poor. As the Indian government is fond of noting, sure, they are growing rapidly in income and in carbon dioxide emissions, but they are still a pale shadow of what rich countries like the United States have emitted over the centuries when they were going from poor to rich.

If the poor listen to the rich they could be in big political trouble. And when the fast-growing poor surpass the rich, the tables will turn. China, India, Brazil, and Mexico will then cry out for environmental change because that will protect their future advantaged position, while the relatively poor of that day, one or two or three hundred years from now, will resist policies that hinder their efforts to climb to the top. The rich will even fight wars to keep the rising poor from getting so rich that they threaten the old political order. (The rising poor will win those wars, by the way.)

There is also a natural division between politicians whose constituents care about the planet more than they care about their short-term quality of life—those are few and far between—and politicians whose constituents say they care about the planet but in reality often vote growth, not green. If you doubt it, take a look at the election record of green parties around the democratic world. Moreover, who will endure the political and economic costs when poor countries trot out starving children—children who would not be starving if their families could just keep on burning cow dung! We are quicker to be softhearted than we are to be green, and really, is that so bad?

So how might we solve global warming and make the world in five hundred years look attractive to our future selves? We twenty-first-century folk know of well over a hundred chemical elements and a long list of forces of nature. In Christopher Columbus’s time, people pretty much only knew rain, wind, fire, and earth. They also knew hardly anything about exploiting rain, wind, and fire, but we sure do, and surely we will know more in the future. Rain, wind, and fire—they can and will solve global warming for future generations. I interpret the figures above to suggest that the reason mandatory emission standards will not be so high in 2050 is because few will care to fight that fight. It won’t matter. New wind, rain, and solar technologies will be solving the problem for us.

Читать дальше