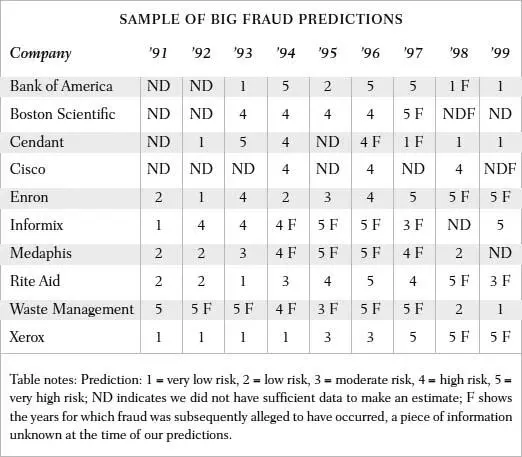

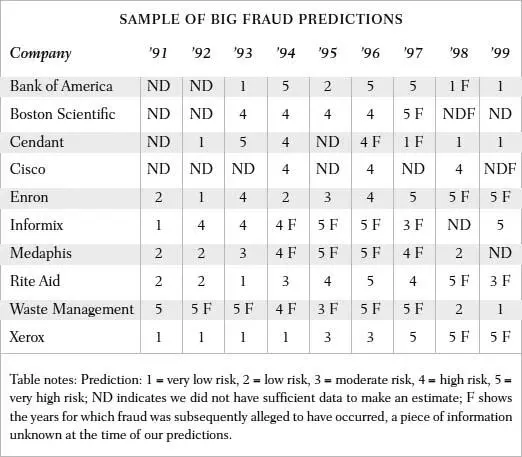

Here’s another way to think about this: The fraud model uses publicly available data. If Arthur Andersen had asked my colleagues and me to develop a theory of fraud in 1996 instead of in 2000, we could have constructed exactly the same model. We could have used exactly the same data from 1989–96 to predict the risk of fraud in different companies for 1997 forward. Those predictions would have been identical to the ones we made in our out-of-sample tests in 2000. The only difference would have been that they could have been useful, because they would then have been about the future.

Clearly, we had a good monitoring system. Our game-theory logic allowed us to predict when firms were likely to be on good behavior and when they were not. It even sorted out correctly the years that an individual firm was at high or low risk. For instance, our approach showed “in advance” (that is, based on the out-of-sample test) when it was likely that Rite Aid was telling the truth in its annual reports and when it was not. The same could be said for Xerox, Waste Management, Enron, and also many others not shown here. We could identify companies that Andersen was auditing that involved high risks, and we could identify companies that Andersen was not auditing that they should have pursued aggressively for future business because those firms were a very low risk. That, in fact, was the idea behind the pilot study Arthur Andersen contracted for. They could use the information we uncovered to maintain up-to-date data on firms. Then the model could predict future risks, and Andersen could tailor their audits accordingly.

Did Andersen make good use of this information? Sadly, they did not. After consulting with their attorneys and their engagement partners—the people who signed up audit clients and oversaw the audits—they concluded that it was prudent not to know how risky different companies were, and so they did not use the model. Instead, they kept on auditing problematic firms, and they got driven out of business. Were they unusual in their seeming lack of commitment to real monitoring and in their failure to cut off clients who were predicted to behave poorly in the near future? Not in my experience. The lack of commitment to effective monitoring is a major concern in game-theory designs for organizations. This is true because, as we will see, too often companies have weak incentives to know about problems. Was the lack of monitoring rational? Alas, yes, it was, even though in the end it meant the demise of Arthur Andersen, LLP. Game-theory thinking made it clear to me that Andersen would not monitor well, but I must say Andersen’s most senior management partners genuinely did not seem to understand the risks they were taking.

At Arthur Andersen, partners had to retire by age sixty-two. Many retired at age fifty-seven. These two numbers go a long way toward explaining why there were weak incentives to pay attention to audit risks. The biggest auditing gigs were brought in by senior engagement partners who had been around for a long time. As I pointed out to one of Andersen’s senior management partners, senior engagement partners had an incentive not to look too closely at the risks associated with big clients. A retiring partner’s pension depended on how much revenue he brought in over the years. The audit of a big firm, like Enron, typically involved millions of dollars. It was clear to me why a partner might look the other way, choosing not to check too closely whether the firm had created a big risk of litigation down the road.

Suppose the partner were in his early to mid-fifties at the time of the audit. If the fraud model predicted fraud two years later, the partner understood that meant a high risk of fraud and therefore a high risk that Andersen (or any accounting firm doing the audit) would face costly litigation. The costs of litigation came out of the annual funds otherwise available as earnings for the partners. Of course, this cost was not borne until a lawsuit was filed, lawyers hired, and the process of defense got under way. An audit client cooking its books typically was not accused of fraud until about three years after the alleged act. This would be about five years after the model predicted (two years in advance) that fraud was likely. Costly litigation would follow quickly on the allegation of fraud, but it would not be settled for probably another five to eight years, or about ten or so years after the initial prediction of risk. By then, the engagement partner who brought in the business in his early to mid-fifties was retired and enjoying the benefits of his pension. By not knowing the predicted risk ten or fifteen years earlier, the partner ensured that he did not knowingly audit unsavory firms. Therefore, when litigation got under way, the partner was not likely to be held personally accountable by plaintiffs or the courts. Andersen (or whichever accounting firm did the audit) would be held accountable (or at least be alleged to be accountable), as they had deep pockets and were natural targets for litigation, but then the money for the defense was coming out of the pockets of future partners, not the partner involved in the audit of fraudulent books a decade or so earlier. The financial incentive to know was weak indeed.

When I suggested to a senior Andersen management partner that this perverse incentive system was at work, he thought I was crazy—and told me so. He thought that clients later accused of fraud must have been audited by inexperienced junior partners, not senior partners near retirement. I asked him to look up the data. One thing accounting firms are good at is keeping track of data. That is their business. Sure enough, to his genuine shock, he found that big litigations were often tied to audits overseen by senior partners. I bet that was true at every big accounting firm, and I bet it is still true today. So now we can see, as he saw, why a partner might not want to know that he was about to audit a firm that was likely to cook its books.

Why didn’t the senior management partners already know these facts? The data were there to be examined. If they had thought about incentives more carefully, maybe they would have saved the partnership from costly lawsuits such as those associated with Enron, Sunbeam, and many other big alleged frauds. Of course, they were not in the game-theory business, and so they didn’t think as hard as they could have about the wrongheaded incentives designed into their partnership (and most other partnerships, for that matter).

On the plus side, management’s incentives were better than those of the engagement partners. Senior managers seemed more concerned about the long-term performance of the firm. Maybe that was the result of what we call a selection effect, as people concerned about the firm’s well-being may have been more likely candidates to become senior management. Still, they also had an incentive to help their colleagues bring in business, and that meant that they were interested in making it easy for their colleagues to sign up as many audit engagements as possible. They may have preferred to avoid problems with bad clients, but the senior managers could live with not knowing about future trouble if that helped to keep their colleagues happy and business pouring in. Thus, senior management’s incentives were not quite right either. Effective monitoring had benefits for them, but it was costly in revenue and especially in personal relations. Many senior management partners tolerated slack monitoring as the solution to this problem, and likely did a quick risk calculation that litigation—not collapse—was the worst that a fraudulent client could visit upon the firm. Let’s face it, many of us would do the same thing.

Читать дальше