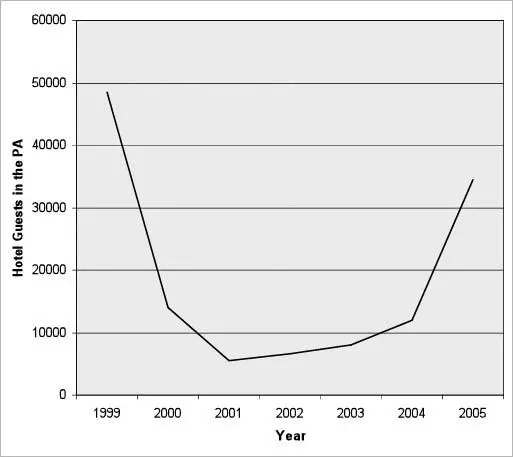

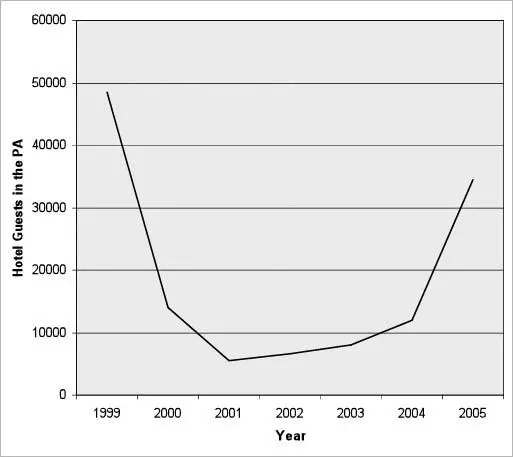

And what is the Palestinian experience like? As I mentioned, it is harder to get equivalent data for the PA, but still there is plenty of evidence that the picture is grim. For instance, there were about 90 hotels in the PA before the intifada that started in late 2000. By the end of 2001 the number had dropped precipitously to around 75. Naturally, hotel openings and closings result from how much business they do. Figure 7.2 shows the number of hotel guests in the PA for each year from 1999 through 2005, as reported by the Palestinian Authority. 4The intifada produced a quick, intense, and easily anticipated response: hotel stays—and tourism in general—plummeted. Estimates from the PA suggest a loss of 600 million tourist dollars between the second intifada’s inception in September 2000 and July 2002. Annual PA tourism revenue in that same period was only $300 million, so the loss was as large as the total tourist revenue. Keep these numbers in mind. We will return to them.

With these facts under our belts, we can work through the game-theory logic that points to the attractiveness of tourist tax dollars as a path toward peace. Imagine, for instance, that President Obama’s government or the United Nations presses the Israeli and Palestinian Authority governments to share with each other tax revenues arising exclusively from tourism and then administers the distribution of the funds. Each side’s share of those tax dollars is to be in direct proportion to its current proportion of the total Israeli and Palestinian populations in the PA and Israel.

FIG. 7.2. Tourism in the Palestinian Authority Since the 2000 Intifada

The tourist tax revenue arrangement need not last forever. It must include an irrevocable commitment for it to persist for a long time (say twenty years), and it is important that this tax revenue sharing be tied to a fixed formula based on the current populations and not on future changes in those populations. Opening the formula to renegotiation could create perverse incentives. It is also essential that the definition of tax revenue originating from spending by tourists be based on predetermined rules for estimating this source of income. Independent accounting firms might be used to provide a standard way to define and identify tourist revenue and the taxes derived from it. This tax revenue would then be allocated to each side over the agreed duration of the program based on a onetime fixed population-based formula with no questions asked.

Some tourist-derived tax revenues are obvious. Hotels check the passports of foreign visitors, and so, as we saw, it is straightforward to know how many tourists checked in, what their hotel bills were, and what were the tax portions of those bills. For every foreigner staying in a hotel—whether strictly a tourist or claiming some business purpose—one might stipulate that the taxes on that hotel stay go into the tourist tax revenue pot. It will be necessary to devise a good monitoring system to prevent underreporting, but that is probably something governments already have dealt with.

Restaurants don’t have as obvious a way of determining who their foreign guests are, but perhaps accountants can find a clever way to approximate the percentage of a restaurant’s taxes that is attributable to tourists. This might depend on the location of the restaurant, the proportion of foreign hotel guests in the area, the location of the bank for payments made by credit card, or many other criteria. The same might be true for shops. Those selling souvenirs, for instance, are likely to have more tourist-based revenue than those selling groceries. At passport control, visitors declare whether the purpose of their visit is business or pleasure. There, too, it is possible to create a revenue formula that approximates how much is spent by those saying they are tourists. Anyway, I am not trying to do the job of accountants, and I certainly am not qualified to do so. Accountants will be good at setting up sensible rules to identify the relevant sources of tax revenue, especially if their fees are also tied to that revenue.

On the population side, if Palestinians currently make up 40 percent of the population in the area, then 40 percent of the tourist tax dollars (or shekels, or any other currency) automatically goes to the Palestinian Authority’s recognized government and 60 percent to the recognized Israeli government. Government recognition could be determined by who selects the personnel in the Palestinian and Israeli delegations to the United Nations. This avoids the risk of a dispute over who constitutes the relevant government, since general diplomatic recognition is itself a contentious issue between the Israelis and Palestinians. Just who the Palestinians and Israelis “are” should be defined in terms of people residing in the area and should not include diaspora populations. To include them will result in the meaning of “Palestinian” and “Israeli” being manipulated for political and economic gain. The money distributed is then dictated by how many tourists come and how much they spend, regardless of whether they spend more or less in Israel, Palestine, or disputed territory. Furthermore, there are no restrictions on how the Israelis or Palestinians spend the money received under this program. If leaders invest this money in improving the quality of life for their people, that’s great. If they want to sock it away in a secret bank account, that is between them and their constituents. The key to success is that the money is neither given as a reward for advancing peace nor withheld as a punishment for hindering peace.

Recall the current situation. Israel expects to bring in about $4 billion in 2008 from tourism and expects, with peace, that this will grow sharply over the next several years. Based on the evidence in figure 7.1, we can estimate that tourist revenue would grow 50 percent relative to what it has been since 2001 if peace prevails. Probably Palestinians in the PA would experience an even greater increase in tourist earnings, as tourism seems to respond more sharply to violence in their region than in Israel. This is not surprising, given that they bear the brunt of the deaths. So, with peace, Israeli revenue would rise from about $4.2 billion in 2008 to (at least) $6.3 billion once a lasting peace was established. Palestinian revenue from tourism would probably increase from $300 million to (at least) $600 million, the amount they earned from tourism in 1999, the year before the second intifada began.

Current total tourist revenue with ongoing violence is reasonably estimated at $4.5 billion for Israel and the PA combined. With peace, the estimate rises to $6.9 billion. Assuming a 20 percent average tax rate on tourism earnings, this means a tax revenue pot worth $1.4 billion with peace compared to $900 million with ongoing violence.

Without a tax-sharing agreement and without peace, Israel’s tax revenue (continuing to assume a 20 percent tax take) from tourism is projected to be $840 million in 2008 or 2009, while the PA’s tax revenue from tourism is projected to be $60 million. With a 60-40 revenue sharing arrangement and peace, Israel’s tax take from tourism is projected to be at least $830 million—essentially a wash in terms of tax earnings between war and peace. The PA’s projected tax take under the proposed plan is $550 million, a more than ninefold increase, not to mention an increase in total revenue for the PA of around $1 billion, equivalent to a 20 percent increase in GDP. That’s serious economic growth!

Okay, so we’ve seen the numbers. Now let’s follow the logical stream. What we have seen is that so long as terrorist attacks or other forms of violence persist at a significant level, far fewer tourists visit Israeli-controlled or Palestinian-controlled sites. When there is significant violence, there will be little tourist income to distribute. Thus, if the Palestinian leadership does not engage in effective counterterrorism, it will get few, if any, funds. It will not be deprived of funds, as it is so often, merely because the Israelis or the international community do not like its policies. Money will not be withheld or payment made contingent on the Palestinians doing what anyone else demands. Money will flow or dry up purely because tourists abhor violence in the places they want to visit. If the Palestinians crack down on the sources of terrorism or other forms of attacks against Israel, then the decreased violence will almost surely be followed by a significant increase in tourism. If tourism increases ever so slightly more than my conservative estimates, decreased violence will mean more tax revenue for both governments.

Читать дальше