There was no one behind us and she was talking to my husband. It was his diagnosis and our world shattered around us the moment the consultant uttered those words. So many people have been in exactly the same position; I’m sure they’ve felt totally alone, just as we did. There were words floating around that no one wants applied to them or to someone they love – chronic myeloid, oncology, chemotherapy. All of these words are so loaded. When you hear them being said to the person you share your life with, it’s like a bomb exploding. You wish that the clock could be turned back – not weeks or months but to that moment before you heard the word ‘cancer’.

I’d worked in healthcare for years and I think I would have known what to say to someone else, but this was Chris. He was the man who had changed my life, who had made me happy and allowed me to be the person I had always wanted to be. He had seen me through my own health scares and had always been such a good person. Maybe everyone starts to think how unfair things are, and, of course, no one deserves cancer, but what had Chris ever done to harm anyone? We had been through so much over the years that it seemed an act of unspeakable cruelty to throw this at us too.

We had never considered cancer a possibility. We had come to hospital that day to find out about kidney stones. It turned out that when Chris had seen the GP (only the day before but it felt like a lifetime ago), his spleen had been three times the size it should have been, which is one of the first signs of this type of cancer. His white cell count was reading 150 when it should have been 5. If he hadn’t gone to the doctor when he did, he would have been dead within six months. Now he had a fighting chance, but it would be far from plain sailing.

It was a terrible time. Chris had to get a bone marrow biopsy, which was a horrible process, a bone marrow harvest, constant blood tests. In fact, he had five bone marrow tests in one year. Initially he didn’t respond to any of the chemotherapy treatment or injections, and his consultant sent him to a specialist in Hammersmith to look at the options. Things seemed very bleak but this man offered us one glimmer of hope. There was a course of treatment with a new drug that had been producing marvellous results in the US. However, it wasn’t on the list of accepted medicines in this country. We were sent home with the information about it, aware that the consultant believed that this was really Chris’s only option. If he couldn’t get access to the drug, there was very little else that could be done.

Chris went back to his own consultant, who said that it was very unlikely that the local health authority would authorize a prescription. The drug cost over £17,000 a year and the budget simply wouldn’t allow for it. I was furious but what could we do? ‘Move to Scotland,’ he said. ‘They give it out like sweets up there. In the meantime, I’ll write to the health authority and see what they say, but I really think there’s very little chance. I’m so sorry.’

When Chris and I went home that night, it was difficult to be optimistic. His future was in the hands of faceless bureaucrats who would look at their balance sheets rather than the human cost of not authorizing the drug we now felt to be our only hope. I clung to what the doctor had said. I had no aversion to moving house; I’d done it plenty of times before, and this time it would be for a better reason than itchy feet. ‘Why don’t we move to Scotland?’ I said to Chris. He had worked there many times and liked it, and I would do anything to increase his chances of surviving. We discussed it well into the night, and I would have been quite happy to start packing the next day, but Chris is more pragmatic and suggested we wait to see what the health authority said; perhaps they would surprise everyone.

They didn’t. They refused the application.

The consultant was furious. He had done more research by this time and concurred completely with the Hammersmith doctor that this drug would give Chris the best chance. He went back to the health authority many times, pleading the case, making strong arguments, but they were difficult. In the end, he wrote the prescription anyway.

It was a miracle drug. Chris was in remission within a year and his case persuaded the authority to prescribe it much more freely when they saw the results. I was still so angry though. It infuriated me that my husband’s health, his life, had been considered to be worth so little. If that drug had never been prescribed, he wouldn’t be here today nor would all the other people who were given it as a result of his test case.

While Chris was terribly ill, the cats sensed something was going on. They became very gentle and watchful with him, and there always seemed to be one of our furry boys or girls sitting beside him when he was too weak to move or too sick from the treatment to get off the chair. While humans sometimes feel awkward or useless in the face of serious illness and the possibility of death, animals seem to take it in their stride, offering love and comfort in a simple way that does so much to help.

Ginny used to curl up beside him no matter how ill Chris was. She gave him such love, and even used to bring him presents of worms and baby frogs. There was never a mark on them, even though she used to carry them home in her mouth. She would deposit them in front of Chris as if she needed to give him something. Cats seem to need to do things for us just as we need to do things for them.

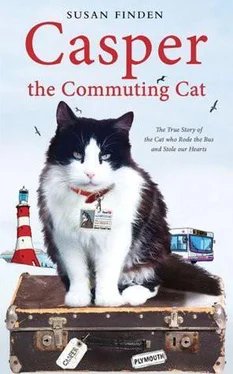

As Chris gradually got better, I felt that we had escaped. Perhaps now we could settle into a normal life, free of worry and concern. Casper’s adventures brought joy to our days, and he managed, in some part, to tackle and negate the terrible negativity that I’d previously felt about humanity.

CHAPTER 24

Casper’s Passing

It was 8.45a.m. on 14 January 2010 when I got the knock at my door that I’d always dreaded.

I was halfway through getting dressed when I heard the noise. It could have been anyone, I suppose – a delivery, some early post, a neighbour. But I knew I just knew, as I walked down the stairs, that as soon as I opened the door, the rug would be pulled out from under me. Do we have some sort of sixth sense when bad things, awful things, are about to affect our lives? Not always – there can be a phone call in the middle of the night that we never expected or a letter that contains information that will change our lives, and they are bolts from the blue. However, I’ve always had feelings about things – premonitions and senses. On this day I desperately wanted to be wrong, but a sense of foreboding warned me against opening the door, told me not to listen to whatever the person on the other side had to say. Sadly, I had no choice. I had to open the door.

Waiting for me on the other side was a lady I vaguely knew. She lived in the same street and I often saw her walking past with her little girl. We had said ‘hello’ and exchanged a few words about Casper from time to time, and she was always friendly and interested in what he was up to. That day she was as white as a ghost and shaking.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she said. ‘I’m not sure how to tell you this but . . . it’s Casper. He’s been hit.’

I listened to the words but they were no surprise to me. Since the moment I’d heard the doorbell, I’d known this was it. This was the moment when all my worst nightmares were about to come true. I felt as if the woman’s voice was coming through a tunnel as she continued to tell me what had happened. It came to me in fragments . . .

There was a car . . . a taxi . . .

Going too fast . . . speeding ...

If he had crossed the road a moment earlier or a moment later . . . he didn’t stand a chance . . .

Читать дальше