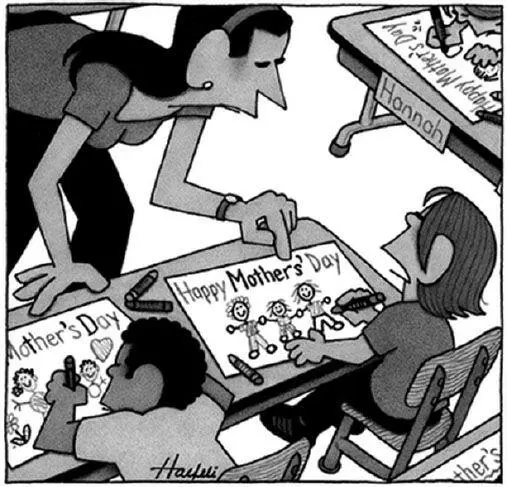

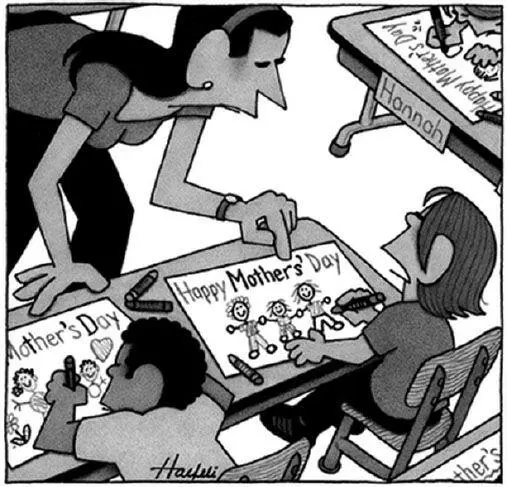

The last of the great apostrophe errors is explained in this cartoon, in which the boy shows that an unconventional family does not necessarily lead to unconventional punctuation:

“I have two mommies. I know where the apostrophe goes.”

The possessive of a singular is spelled ’s: He is his mother’s son. The possessive of a regular plural is spelled s’: He is his parents’ son, or, with a same-sex couple, He is his mothers’ son. As for names ending in s like Charles and Jones , go with grammatical logic and treat them as the singulars they are: Charles’s son, not Charles’ son. Some manuals stipulate an exception for Moses and Jesus, but grammarians should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, and the exception in fact applies to other ancient names ending in s ( Achilles’ heel, Sophocles’ play ). 67It also applies to modern names which already end with a ses sound, whose genitives contain the tongue-twister seses ( Kansas’, Texas’ ).

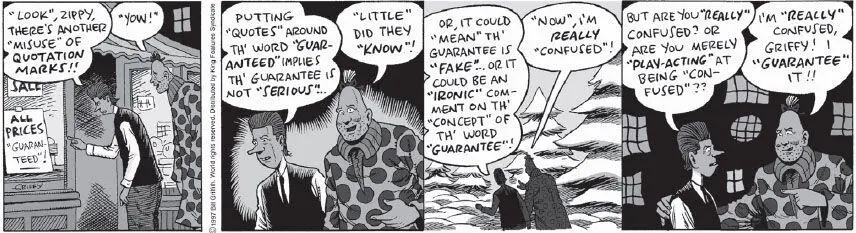

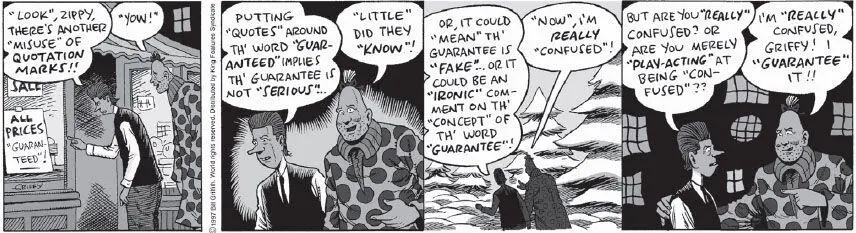

quotation marks.Another insult to punctuational punctiliousness is the use of quotation marks for emphasis, commonly seen in signs like WE SELL “ICE”, CELL PHONES MAY “NOT” BE USED IN THIS AREA, and the disconcerting “FRESH” SEAFOOD PLATTER and even more disconcerting EMPLOYEES MUST “WASH HANDS”. The error is common enough to have inspired the cartoon on the following page.

Why do so many signmakers commit the error? What they are doing is what we all used to do in the Paleolithic days of word processing, when terminals and printers lacked italics and underlining (and what many of us still do when composing email in plain text format), which is to emphasize a word by bracketing it with symbols, like *this *or _this_ or . But not like “this”. As Griffy explains in the cartoon, quotation marks already have a standard function: they signal that the author is not using words to convey their usual meaning but merely mentioning them as words. If you use quotation marks for emphasis, readers will think you’re unschooled or worse.

No discussion of the illogic of punctuation would be complete without the infamous case of the ordering of a quotation mark with respect to a comma or period. The rule in American publications (the British are more sensible about this) is that when quoted material appears at the end of a phrase or sentence, the closing quotation mark goes outside the comma or period, “like this,” rather than inside, “like this”. The practice is patently illogical: the quotation marks enclose a part of the phrase or sentence, and the comma or period signals the end of that entire phrase or sentence, so putting the comma or period inside the quotation marks is like Superman’s famous wardrobe malfunction of wearing his underwear outside his pants. But long ago some American printer decided that the page looks prettier without all that unsightly white space above and to the left of a naked period or comma, and we have been living with the consequences ever since.

The American punctuation rule sticks in the craw of every computer scientist, logician, and linguist, because any ordering of typographical delimiters that fails to reflect the logical nesting of the content makes a shambles of their work. On top of its galling irrationality, the American rule prevents a writer from expressing certain thoughts. In his semi-serious 1984 essay “Punctuation and Human Freedom,” Geoffrey Pullum discusses the commonly misquoted first two lines of Shakespeare’s King Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York.” 68Many people misremember it as “Now is the winter of our discontent”, full stop. Now suppose one wanted to comment on the error by writing:

Shakespeare’s King Richard III contains the line “Now is the winter of our discontent”.

This is a true sentence. But an American copy editor would change it to:

Shakespeare’s King Richard III contains the line “Now is the winter of our discontent.”

But this is a false sentence, or at least there’s no way for the writer to make it unambiguously true or false. Pullum called for a campaign of civil disobedience, and with the subsequent rise of the Internet his wish has come true. Many logic-conscious and computer-savvy writers have taken advantage of the freedom from copy editors they enjoy on the Web and have explicitly disavowed the American system, most notably on Wikipedia, which has endorsed the alternative called Logical Punctuation. 69Punctuation nerds may have noticed that I myself recently defied the American rule in four places (underlined):

The final insult to punctuational punctiliousness is the use of quotation marks for emphasis, commonly seen in signs like WE SELL “ICE”, CELL PHONES MAY “NOT” BE USED IN THIS AREA, and the disconcerting “FRESH” SEAFOOD PLATTER and even more disconcerting EMPLOYEES MUST “WASH HANDS”.

But not like “this”.

Many people misremember it as “Now is the winter of our discontent”, full stop.

These acts of civil disobedience were necessary to make it clear where the punctuation marks went in the examples I was citing. You should do the same if you ever need to discuss quotations or punctuation, if you write for Wikipedia or another tech-friendly platform, or if you have a temperament that is both logical and rebellious. The movement may someday change typographical practice in the same way that the feminist movement in the 1970s replaced Miss and Mrs. with Ms. But until that day comes, if you write for an edited American publication, be prepared to live with the illogic of putting a period or comma inside quotation marks.

I hope to have convinced you that dealing with matters of usage is not like playing chess, proving theorems, or solving textbook problems in physics, where the rules are clear and flouting them is an error. It is more like research, journalism, criticism, and other exercises of discernment. In considering questions of usage, a writer must critically evaluate claims of correctness, discount the dubious ones, and make choices which inevitably trade off conflicting values.

Anyone who reviews the history of prescriptive grammar can’t help but be struck by the misplaced emotion the topic evokes. At least since Henry Higgins decried “the cold-blooded murder of the English tongue,” the self-proclaimed defenders of high standards have been outdoing each other with tasteless invective. 70David Foster Wallace expressed “despair” at the “Evil” inherent in “voguish linguistic methane.” David Gelernter refers to advocates of singular they as “language rapists,” while John Simon has likened the people who use words in ways he disapproves of to slave traders, child molesters, and the guards at Nazi death camps. The hyperbole often shades into misanthropy, as when Lynne Truss suggests that people who misuse apostrophes “deserve to be struck by lightning, hacked up on the spot and buried in an unmarked grave.” Robert Hartwell Fiske, after calling humongous a “hideous, ugly word,” adds, “Though it’s not fair to say that people who use the word are hideous and ugly as well, at some point we come to be—or at the least are known by—what we say, what we write.”

The irony, of course, is that all too often it is the targets of the vituperation who have history and usage on their side, and the vilifiers who are full of baloney. Geoffrey Pullum, whose Language Log analyzes claims about the use and misuse of language, has noted the tendency among faultfinders “to move straight to high dudgeon, skipping right over the stage where you check the reference books to make sure you have something to be in high dudgeon about. … People just don’t look in reference books when it comes to language; they seem to think their status as writers combined with their emotion of anger gives them all the standing they need.” 71

Читать дальше