*Your lecture is scheduled for 5 PM, it is preceded by a meeting.

Your lecture is scheduled for 5 PM; it is preceded by a meeting.

Your lecture is scheduled for 5 PM—it is preceded by a meeting.

Your lecture is scheduled for 5 PM, but it is preceded by a meeting.

Your lecture is scheduled for 5 PM; however, it is preceded by a meeting.

*Your lecture is scheduled for 5 PM, however, it is preceded by a meeting.

The other bit of comma jargon that has spread beyond the world of copyediting is the serial comma or Oxford comma. It pertains to the second major function of the comma, which is to separate the items in a list. Everyone knows that when two items are joined with a conjunction, they cannot have a comma joining them, too: Simon and Garfunkel, not Simon, and Garfunkel. But when three or more items are joined, a comma must introduce every subsequent item except—and here comes the controversy—the last one: Crosby, Stills and Nash; Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. The controversial question is whether you should also put a comma before the final item, resulting in Crosby, Stills, and Nash , or Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. This is the serial comma. On one side we have most British publishers (other than Oxford University Press), most American newspapers, and the rock group that calls itself Crosby, Stills and Nash . They argue that an item in a list should be introduced either with and or with a comma, not redundantly with both. On the other side we have Oxford University Press, most American book publishers, and the many wise guys who have discovered that omitting a serial comma can result in ambiguity: 65

Among those interviewed were Merle Haggard’s two ex-wives, Kris Kristofferson and Robert Duvall.

This book is dedicated to my parents, Ayn Rand and God.

Highlights of Peter Ustinov’s global tour include encounters with Nelson Mandela, an 800-year-old demigod and a dildo collector.

The absence of a serial comma in a list of phrases can also create garden paths. He enjoyed his farm, conversations with his wife and his horse momentarily calls to mind the famous Mister Ed, and a reader who is unfamiliar with the popular music of the 1970s might well be tripped up by the sentence on the left, stumbling over the mythical duo Nash and Young and the run-on sequence Lake and Palmer and Seals and Crofts:

Without the serial comma:

With the serial comma:

My favorite performers of the 1970s are Simon and Garfunkel, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Emerson, Lake and Palmer and Seals and Crofts.

My favorite performers of the 1970s are Simon and Garfunkel, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, and Seals and Crofts.

I say that unless a house style forbids it, you should use the serial comma. And if you’re enumerating lists of lists, then you can eliminate all ambiguity by availing yourself of one of the few punctuation tricks in English that explicitly signal tree structure, the use of a semicolon to demarcate lists of phrases containing commas:

My favorite performers of the 1970s are Simon and Garfunkel; Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young; Emerson, Lake, and Palmer; and Seals and Crofts.

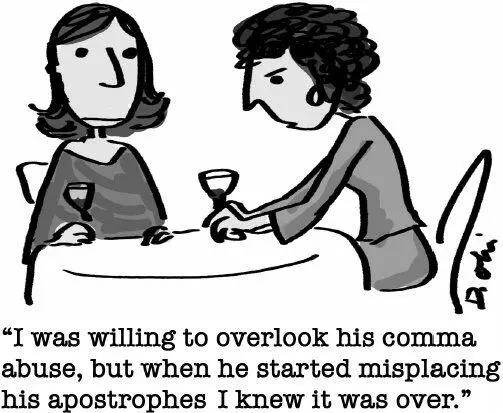

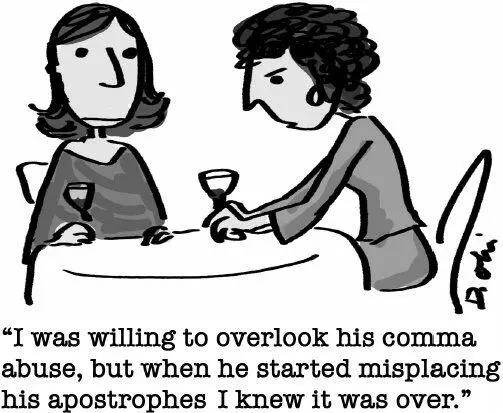

apostrophes.The serial comma is not the only punctuation sin that will hurt you in life:

The disenchanted girlfriend, I surmise, is referring to three common errors with apostrophes. If I were her companion, I would advise her to consider which quality she values more in a soulmate, logic or literacy, because each of the errors is thoroughly systematic, albeit contrary to accepted usage.

The first is the grocer’s apostrophe, as in APPLE’S 99¢ EACH. The error is by no means restricted to grocers; the British press had a field day when a protesting student was spotted with the sign DOWN WITH FEE’S. The rule is straightforward: the plural s may not be connected to a noun using an apostrophe, but must be jammed right up against it without punctuation— apples, fees.

The error seduces grocers and students with three lures. One is that it is easy to confuse the plural s with the genitive ’s and the contraction ’s , both of which require an apostrophe: the apple’s color is impeccable, as is This apple’s sweet. Second, the grocers are, if anything, too conscious of grammatical structure: they seem to want to signal the difference between the phoneme s that is an intrinsic part of a word and the morpheme – s that is tacked on to mark the plural, as in the distinction between lens and pens ( pen + – s ), or species and genies. Marking a morpheme boundary is particularly tempting with words that end in vowels, because the correct, unpunctuated plural makes the word look like something else entirely, as in radios (which looks like adios ) and avocados (which looks like asbestos ). Perhaps if the grocers had their way and plurals were consistently marked with apostrophes ( radio’s, avocado’s, potato’s, and so on), no one would ever mistakenly refer to a kudo (the word is kudos, a singular Greek noun meaning “praise”), and Dan Quayle would have been spared the embarrassment of publicly miscorrecting a schoolchild’s potato to potatoe . Most seductively of all, the rule banning apostrophes in plurals is not as straightforward as I said it was. With some nouns, an apostrophe really is (or at least was) legitimate. The apostrophe is mandatory with a letter of the alphabet ( p’s and q’s ) and common with words mentioned as words (There are too many however ’s in this paragraph ), unless they are clichés like dos and don’ts or no ifs, ands, or buts. Before the recent trend toward light punctuation, apostrophes were often used to pluralize years ( the 1970’s ), abbreviations ( CPU’s ), and symbols (@ ’s ), and in some newspapers (such as the New York Times ) they still are. 66

The rules may not be logical, but if you want your literate lover not to leave you, don’t pluralize with an apostrophe. It’s also a good idea to know when to keep an apostrophe away from a pronoun. Dave Barry’s alter ego Mr. Language Person fielded the following question:

Q: Like millions of Americans, I cannot grasp the extremely subtle difference between the words “your” and “you’re.”

A: … The best way to tell them apart is to remember that “you’re” is a contraction, which is a type of word used during childbirth, as in: “Hang on, Marlene, here comes you’re baby!” Whereas “your” is, grammatically, a prosthetic infarction, which means a word that is used to score a debating point in an Internet chat room, as in: “Your a looser, you morron!”

The first part of Mr. Language Person’s answer is correct: an apostrophe must be used to mark the contraction of an auxiliary with a pronoun, as in you’re (you are), he’s (he is), and we’d (we would). And his first example (assuming you get the joke that you’re baby is mispunctuated) is also correct: an apostrophe is never used to mark the genitive (possessive) of a pronoun, no matter how logical it may seem to do so. Although we write the cat’s pajamas and Dylan’s dream, as soon as you replace the noun with a pronoun the apostrophe goes out the window: one must write its pajamas, not it’s pajamas; your baby, not you’re baby; their car, not they’re car; Those hats are hers, ours, and theirs, not Those hats are her’s, our’s, and their’s. Deep in the mists of time, someone decided that an apostrophe doesn’t belong in a possessive pronoun, and you’ll just have to live with it.

Читать дальше