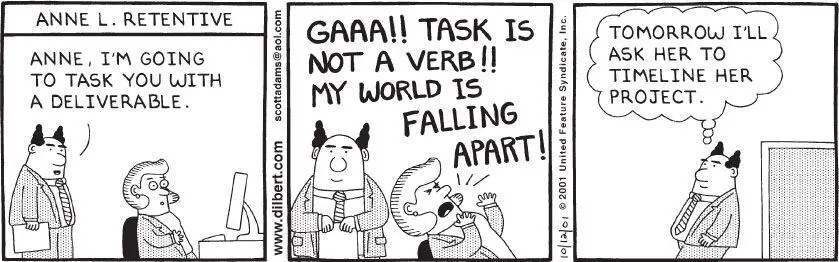

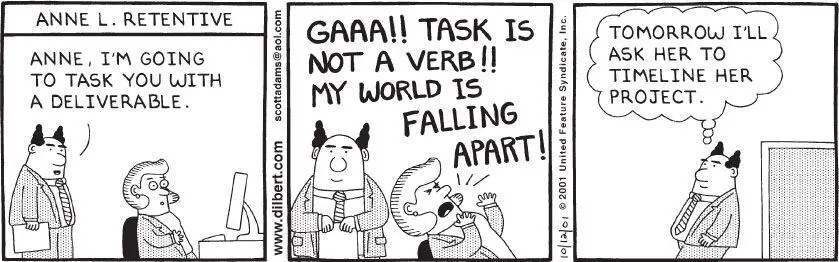

verbing and other neologisms.Many language lovers recoil from neologisms in which a noun is repurposed as a verb:

Dilbert © 2001 scott Adams. Used by permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.

Other denominal verbs which have shattered the worlds of anal-retentives include author, conference, contact, critique, demagogue, dialogue, funnel, gift, guilt, impact, input, journal, leverage, mentor, message, parent, premiere, and process (in the sense of “think over”).

But the retentives are misdiagnosing their anomie if they blame it on the English rule that converts nouns into verbs without an identifying affix such as – ize, –ify, en–, or be–. (Come to think of it, they hate many of those, too, like incentivize, finalize, personalize, prioritize , and empower. ) Probably a fifth of English verbs started out life as nouns or adjectives, and you can find them in pretty much any paragraph of English prose. 36A glance at the most emailed stories in today’s New York Times turns up arriviste verbs such as biopsy, channel, freebase, gear, headline, home, level, mask, moonlight, outfit, panic, post, ramp, scapegoat, screen, sequence, showroom, sight, skyrocket, stack up, and tan, together with verbs derived from nouns or adjectives by affixation such as cannibalize, dramatize, ensnarl, envision, finalize, generalize, jeopardize, maximize, and upend.

The English language welcomes converts to the verb category and has done so for a thousand years. Many novel verbs that set purists’ teeth on edge become unexceptionable to their grown children. It’s hard to get worked up, for example, over the now-indispensable verbs contact, finalize, funnel, host, personalize, and prioritize. Even many of the denominal verbs that gained traction in the past couple of decades have earned a permanent place in the lexicon because they convey a meaning more transparently and succinctly than any alternative, including incentivize, leverage, mentor, monetize, guilt (as in She guilted me into buying a bridesmaid’s dress ), and demagogue (as in Weiner tried to demagogue the mainly African-American crowd by playing the victim ).

What really gets on the nerves of Ms. Retentive and her ilk is not verbing per se but neologisms from certain walks of life. Many people are irritated by buzzwords from the cubicle farm, such as drill down, grow the company, new paradigm, proactive, and synergies. They also bristle at psychobabble from the encounter group and therapy couch, such as conflicted, dysfunctional, empower, facilitate, quality time, recover, role model, survivor, journal as a verb, issues in the sense of “concerns,” process in the sense of “think over,” and share in the sense of “speak.”

Recently converted verbs and other neologisms should be treated as matters of taste, not grammatical correctness. You don’t have to accept all of them, particularly instant clichés like no-brainer, game-changer, and think outside the box, or trendy terms which tart up a banal meaning with an aura of technical sophistication, like interface, synergy, paradigm, parameter, and metrics.

But many neologisms earn a place in the language by making it easy to express concepts that would otherwise require tedious circumlocutions. The fifth edition of the American Heritage Dictionary, published in 2011, added ten thousand words and senses to the edition published a decade before. Many of them express invaluable new concepts, including adverse selection, chaos (in the sense of the theory of nonlinear dynamics) , comorbid, drama queen, false memory, parallel universe, perfect storm, probability cloud, reverse-engineering, short sell, sock puppet, and swiftboating . In a very real sense such neologisms make it easier to think. The philosopher James Flynn, who discovered that IQ scores rose by three points a decade throughout the twentieth century, attributes part of the rise to the trickling down of technical ideas from academia and technology into the everyday thinking of laypeople. 37The transfer was expedited by the dissemination of shorthand terms for abstract concepts such as causation, circular argument, control group, cost-benefit analysis, correlation, empirical, false positive, percentage, placebo, post hoc, proportional, statistical, tradeoff, and variability. It is foolish, and fortunately impossible, to choke off the influx of new words and freeze English vocabulary in its current state, thereby preventing its speakers from acquiring the tools to share new ideas efficiently.

Neologisms also replenish the lexical richness of a language, compensating for the unavoidable loss of words and erosion of senses. Much of the joy of writing comes from shopping from the hundreds of thousands of words that English makes available, and it’s good to remember that each of them was a neologism in its day. The new entries in AHD 5 are a showcase for the linguistic exuberance and recent cultural history of the Anglosphere:

Abrahamic, air rage, amuse-bouche, backward-compatible, brain freeze, butterfly effect, carbon footprint, camel toe, community policing, crowdsourcing, Disneyfication, dispensationalism, dream catcher, earbud, emo, encephalization, farklempt, fashionista, fast-twitch, Goldilocks zone, grayscale, Grinch, hall of mirrors, hat hair, heterochrony, infographics, interoperable, Islamofascism, jelly sandal, jiggy, judicial activism, ka-ching, kegger, kerfuffle, leet, liminal, lipstick lesbian, manboob, McMansion, metabolic syndrome, nanobot, neuroethics, nonperforming, off the grid, Onesie, overdiagnosis, parkour, patriline, phish, quantum entanglement, queer theory, quilling, race-bait, recursive, rope-a-dope, scattergram, semifreddo, sexting, tag-team, time-suck, tranche, ubuntu, unfunny, universal Turing machine, vacuum energy, velociraptor, vocal percussion, waterboard, webmistress, wetware, Xanax, xenoestrogen, x-ray fish, yadda yadda yadda, yellow dog, yutz, Zelig, zettabyte, zipline

If I were allowed to take just one book to the proverbial desert island, it might be a dictionary.

who and whom .When Groucho Marx was once asked a long and orotund question, he replied, “Whom knows?” A 1928 short story by George Ade contains the line “‘Whom are you?’ he said, for he had been to night school.” In 2000 the comic strip Mother Goose and Grimm showed an owl in a tree calling “Whom” and a raccoon on the ground replying “Show-off!” A cartoon entitled “Grammar Dalek” shows one of the robots shouting, “I think you mean Doctor Whom!” And an old Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoon contains the following dialogue between the Pottsylvanian spies Boris Badenov and Natasha Fatale:

NATASHA: Ve need a safecracker!

BORIS: Ve already got a safecracker!

NATASHA: Ve do? Whom?

BORIS: Meem, dat’s whom!

The popularity of whom humor tells us two things about the distinction between who and whom. 38First, whom has long been perceived as formal verging on pompous. Second, the rules for its proper use are obscure to many speakers, tempting them to drop whom into their speech whenever they want to sound posh.

As we saw in chapter 4, the distinction between who and whom ought to be straightforward. If you mentally rewind the transformational rule that moves the wh- word to the front of a sentence, the distinction between who and whom is identical to the distinction between he and him or between she and her, which no one finds difficult. The declarative sentence She tickled him can be turned into the question Who tickled him? in which the wh- word replaces the subject and appears in nominative case, who. Or it can be turned into the question Whom did she tickle? in which the wh- word replaces the object and hence appears in accusative case, whom .

Читать дальше