Bonjour, comment vous appelez-vous?

Bonjour, madame, je m’appelle Mathinna.

Enchanté de fair votre connaissance.

Merci, madame. Je suis enchanté également.

Mathinna grew to love the melody of the language. It seemed to her logical and beautiful—much nicer than English, pocked as it was with maddening contradictions and inelegant phrasings. Though she did like a play that started on a Scottish heath with witches around a cauldron and featured a royal couple who reminded her ever so slightly of Lady Franklin and Sir John. And another about a shipwreck on a remote island that Eleanor decided they should read aloud.

“‘But thy vile race,’” Eleanor intoned, in character as Miranda, “‘Though thou didst learn, had that in’t which good natures / Could not abide to be with. Therefore wast thou / Deservedly confined into this rock, / Who hadst deserved more than a prison.’” And Mathinna-as-Caliban responded, “‘As I told thee before, I am subject to a tyrant, a sorcerer that by his cunning hath cheated me of the island.’”

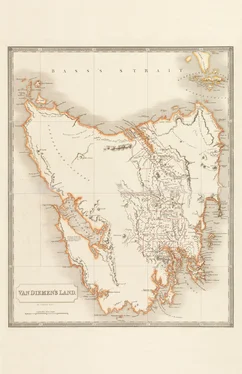

Spinning a wooden sphere, Eleanor identified the seven continents and five oceans. “Here,” she said, putting her finger on a kangaroo-like shape in the northern hemisphere on the other side of the globe from Van Diemen’s Land. “This is where I was born.” She tapped London, and Paris, and Rome—all the important cities, she said—and ran her finger down the spiky coastline to the bottom of Africa, and across a wide blue expanse. “And this is the route we took to get to this godforsaken place. We spent four months at sea!”

Mathinna touched the heart-shaped mass of Van Diemen’s Land. She traced her own reverse journey with her finger, as she’d done on the captain’s map, up the right side of the island to the tiny speck where she was born. On the captain’s map, Van Diemen’s Land had been huge and Flinders Island small. On this globe, it was merely a rock in the ocean, too slight and insignificant to have a name. It was as if the place she loved, and the people on it, had been erased. No one even knew they existed.

In this strange new place Waluka clung to Mathinna. His own fear raised in her a protectiveness that calmed her. He spent most of the day sleeping in a wide pocket of her pinafore, but climbed out now and then to make his way up to her neck, where he nestled against her, nuzzling her with his wet nose. In the evenings she was expected to put him in a cage that was brought to her room for that purpose, but after shutting the door and blowing out the candle, she unlatched the cage and let Waluka run across the floor to the bed.

She spent as little time as possible in her bedroom, with its boarded-up window and looming candle-made shadows. On mild days, when she wasn’t with Eleanor in the schoolroom, she rambled around the cobbled courtyard with Waluka in her pocket, watching the stablemen brush and feed the horses, scratching the backs of the hogs in the piggery and listening to the gossip between the convict maids as they scrubbed laundry and hung it on the clothesline behind the house.

It was generally agreed that Lady Franklin possessed the brains and the ambition to rule this unruly colony, while Sir John, with his knighthood, provided the status. The maids spoke of him with a kind of benevolent contempt. In their eyes, Sir John was a foolish man, constantly getting himself into trouble and barely getting himself out. They recounted endless stories about his haplessness, such as the time he’d charged out of the house shouting for the carriage with his face half shaved and half lathered. They scoffed at how he combed his few remaining strands of hair across the top of his head. They tittered at how comical he appeared on horseback, with his stomach bulging over his trousers, the buttons on his waistcoat straining at the seams.

Sir John had achieved fame as an explorer, but each voyage he’d led was more calamitous than the last. There was one expedition to northern Canada that ended in survivors eating their own boots and possibly each other, and another to the Arctic Circle that grew increasingly dire before the remaining few gave up and fled back to England. Only after a vigorous marketing campaign by Lady Franklin was he rewarded with a knighthood for these failed attempts.

Lady Franklin’s treatment of Eleanor was another source of amusement. Eleanor was the product of Sir John’s first marriage to a woman who’d died tragically young; Lady Franklin, who had no children of her own, tolerated her with barely concealed impatience. When she couldn’t avoid Eleanor, she poked at her with criticism masquerading as concern. “Are you quite well? You’re frightfully pale.” “Dear girl, that dress is so unflattering! I must have a word with the seamstress.”

Mathinna saw this for herself one day when she and Eleanor passed Lady Franklin in the corridor. “Posture, Eleanor,” Lady Franklin said, barely breaking stride. “You don’t want to be mistaken for a scullery maid.”

Eleanor looked as if she’d been splashed in the face with water. “Yes, ma’am,” she said. But when Lady Franklin disappeared around the corner, she slumped comically, tucking her arms into wings and crouching into a penguin’s waddle, making Mathinna giggle.

Lady Franklin had little time for Mathinna, preoccupied as she was with entertaining dignitaries, writing in her journal, taking picnics up Mount Wellington on daylong expeditions, and departing on overnight trips with Sir John. But a few times a month she invited a group of ladies, wives of merchants and government officials, to drink tea and eat cake in the red-paneled drawing room, and on these occasions she summoned Mathinna to show off her newly acquired French and good manners.

“What would you like to say to these ladies, Mathinna?”

She curtsied dutifully. “ Je suis extrêmement heureux de vous rencontrer tous.”

“As you can see, the girl has made remarkable progress,” Lady Franklin said.

“Or is a clever mimic, at least,” one of the ladies said behind her fan.

The ladies asked lots of questions. They wanted to know if Mathinna had ever worn proper clothing before coming to Hobart Town. If she ate snakes and spiders. If her father had many wives, if she’d grown up in a hut, if she believed in the occult. They marveled at her brown skin, turning her hands over to inspect her palms. They patted her spongy dark hair and peered inside her mouth to confirm the pinkness of her gums.

Mathinna grew to dread these afternoons in the drawing room. She disliked being pawed over and whispered about. Sometimes she wished she were white, or invisible, just to avoid the stares and whispers, the rude, patronizing questions.

When they tired of her, Mathinna sat in a corner playing patience, a game of solitaire that Eleanor had taught her. As she squared and fanned her cards, she listened to the ladies commiserate about the inconvenience of living so far from civilization. They complained about how they couldn’t get the supplies they wanted—Leghorn bonnets from Tuscany and opera-length kid gloves, mahogany bed frames and glass chandeliers, champagne and foie gras. They bemoaned the lack of skilled artisans. The impossibility of finding good help. The dearth of amusements, like opera and theater. “Good theater,” Lady Franklin clarified. “You can attend an atrocious production in Hobart Town every day of the week.” They fretted about their skin: how it burned and dried out, blistered and freckled, how vulnerable it was to rashes and insect bites.

So many odd customs these ladies had! They stuffed themselves into elaborate costumes: corsets with whalebone stays, hats with bows and ribbons, impractical shoes with pointy heels that disintegrated in the mud and dirt. They ate extravagant meals that upset their stomachs and made them fat. They appeared to exist in a perpetual state of discontent, constantly comparing their lives to those of their contemporaries in London and Paris and Milan. Why did they stay here, Mathinna wondered, if they disliked it so much?

Читать дальше