Then disaster struck. A young lady from a prominent landholding family was brought in complaining of stomach pains and shaking with chills, and had a high fever. His father, having never seen a case of appendicitis, diagnosed typhoid, prescribed morphine for the pain and fasting for the fever, and sent her home. The heiress died in great agony, vomiting blood in the middle of the night, to the disbelieving horror of her family. Their heartbreak required a villain. The doctor and his partner-son were shunned, the practice ruined.

Some months later, an envelope arrived in the post from his roommate at the Royal College. The British government sought qualified surgeons for transport ships and would pay handsomely. It was a particular challenge to find surgeons for the female convict ships because, “to be frank,” his roommate wrote, “the ships are rumored to be floating brothels.”

“A gross exaggeration, as I now know,” Dr. Dunne hastened to add. “Or at least . . . an exaggeration.”

“But you signed on anyway.”

“There was nothing left for me at home. I would’ve had to start somewhere new.”

“Do you regret it?”

The corners of his mouth turned up in bitter comedy. “Every day.”

This was his third voyage, he said. He spent little time with the rough sailors, the boorish captain, or the alcoholic first mate, whose excesses he’d already treated several times. There was no one he could really talk to.

“What would you do, then, if you could do whatever you chose?” she asked.

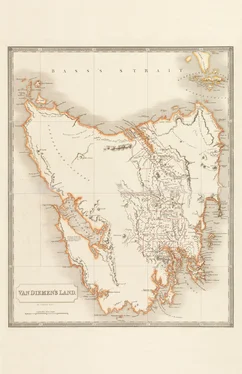

He turned to face her, one arm on the railing. “What would I do? I would open my own practice. Maybe in Van Diemen’s Land. Hobart Town is a small place. I could start again.”

“Starting again,” she said with a catch in her throat. “That sounds nice.”

“Ye should charge for your services,” Olive told Hazel on a rare afternoon away from her sailor. “People take advantage.”

“How’re they gonna pay?” Hazel asked.

“Not your worry. Everybody’s got something to barter.”

Olive was right. Soon enough Hazel was in possession of two quilts, a small store of silver pilfered from sailors’ trunks, dried cod and oat cakes, even a down pillow made by an enterprising convict who plucked geese for the officers’ meals.

“Look at all this,” Evangeline marveled when Hazel lit a taper in a small brass candlestick with a finger loop—another bartered item—and pulled out a sack she’d stuffed under her berth.

“Want something? Help yourselves.”

Evangeline sifted through the sack, with Olive peering over her shoulder. Two eggs, a fork and spoon, a pair of stockings, a white handkerchief . . . wait—

She snatched the handkerchief out of the sack and ran her thumb along the embroidery. “Who gave you this?”

Hazel shrugged. “Dunno. Why?”

“It’s mine.”

“Are ye sure?”

“Of course I’m sure. It was given to me.”

“Ah, sorry, then. Nothing’s safe, is it?”

Evangeline pressed the handkerchief on her bedtick, smoothing it, and folded it into a small square.

“What’s so special about it?” Olive reached for the handkerchief and Evangeline let her take it. Holding it up to the candle, she peered at it closely. “Is this a family crest?”

“Yes.”

“This must be from the cad who . . .” Olive gestured toward Evangeline’s stomach. “C. F. W. Lemme guess. Chester Francis Wentworth,” she said, affecting a snooty accent.

Evangeline laughed. “Close. Cecil Frederic Whitstone.”

“Cecil. Even better.”

“Does he know you’re here?” Hazel asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Does he know you’re carrying his child?”

Evangeline shrugged. It was a question she’d asked herself many times.

Hazel set the candle on the ledge of the berth. “So, Leenie . . . why would ye keep this?”

Evangeline thought of the look on Cecil’s face when he gave her the ring. His boyish eagerness to see it on her finger. “He gave me a ruby ring that had been his grandmother’s. He wrapped it in this handkerchief. Then he went away on holiday and the ruby was found in my room, and I was accused of stealing it. They didn’t notice the handkerchief, so I kept it.”

“Did he return from his trip?”

“I assume he did.”

“Why didn’t he come to your defense, then?”

“I don’t—I don’t know what he knows.”

Olive crumpled the handkerchief in her fist. “I can’t see why you’d want this lousy piece of cloth, after he left ye high and dry.”

Evangeline took it from her. “He didn’t . . .”

But he did, didn’t he?

She fingered the handkerchief’s scalloped edges. Why did she want this lousy piece of cloth?

“It’s—it’s all I have left.” The moment she said it, she knew that this was true. This handkerchief was the only remaining shred from the fabric of her previous life. The only tangible reminder that she’d once been somebody else.

Olive nodded slowly. “Then ye should put it in a place no one’ll find it.”

“There’s a loose floorboard under my berth where I stash some bits and pieces,” Hazel said, smoothing out the handkerchief and folding it. “I can hide it for ye, if ye want.”

“Would you?”

“Later, when no one’s looking.” She tucked the cloth into her pocket. “So what happened to the ruby ring?”

“No doubt on someone else’s finger,” Olive said.

Medea , 1840

Over the next several weeks, the Medea passed the mouth of the Mediterranean, Madeira, and Cape Verde, crossing the Tropic of Cancer and heading toward the equator. By late morning, these days, the sun was hot overhead, the air thick and humid. There was no wind to speak of. What little progress the Medea made was gained by tacking, a job that required great effort by the sailors. The temperature in the lower decks soared above 120 degrees, the humidity so acute it felt like living inside a steaming kettle.

“They’re boiling us alive,” Olive said.

A cloud of malaise hung over the ship. More fell ill. Some women’s feet were covered with oozing black sores, and swollen to double their size. The ones who could read carried their Bibles around with them, mouthing verses from Revelation: And the sea gave up the dead which were in it; and death and hell delivered up the dead which were in them. And Psalm 93: The waves of the sea are mighty, and rage horribly; but yet the Lord, who dwelleth on high, is mightier.

The choice for the convicts was to stay on the main deck and endure the unforgiving sun or suffer in the unventilated hold. The heat made the stink even worse. They aired their bedding, burned sulfur, dusted the surfaces with bleaching powder. Sailors fired pistols below decks in the belief that gunpowder dispelled infectious vapors. But the best the prisoners could hope for in the bowels of the ship was merciful sleep. Mostly, they lay around on the main deck, wrapped in perspiration like gauze, their eyes half closed against the unremitting glare. They made bonnets out of burlap and flour sacks to shade their faces. Some women, not particularly stable to begin with, took to banging their heads against the posts of their berths or the ship railings on the upper deck until they were doused with buckets of water. But most were quiet. It took too much energy to speak. Even the farm animals lolled about, their tongues drooping from their mouths.

Two and a half months after leaving London, the Medea rounded the jagged cliffs and pristine sands of the Cape of Good Hope near the southernmost tip of Africa and headed due east into the Indian Ocean. Ann Darter, the sickly girl whose baby died in Newgate, took a turn for the worse. When she died, Evangeline felt compelled to attend the makeshift service. Ann’s body, in a weighted burlap sack, lay on a plank draped with a Union Jack. As two sailors held the plank on the railing, the surgeon said a few words—“We commit this prisoner to the deep, looking for the resurrection of the body when the sea shall give up her dead”—and tilted his chin at the sailors, who tipped the plank. The body slid from under the flag and splashed into the sea, floating on the surface for a moment before sinking beneath the waves.

Читать дальше