She remembered something her father had told her as he knelt at the hearth one evening, building a fire. Holding up the cut end of a log, he showed her the rings inside, explaining that each one marked a year. Some were wider than others, depending on the weather, he said; they were lighter in winter and darker in summer. All of them fused together to give the tree its solid core.

Maybe humans are like that, she thought. Maybe the moments that meant something to you and the people you’ve loved over the years are the rings. Maybe what you thought you’d lost is still there, inside of you, giving you strength.

The prisoners had nothing to lose, which meant they had no shame. They blew their noses into their sleeves, picked lice from each other’s hair, crushed fleas between their fingers, kicked slithering rats out of the way without a second thought. They swore at the slightest provocation, sang bawdy songs about randy butchers and barmaids with swollen bellies, and openly inspected their monthly rags, stained dark with blood, to assess whether they could use them again. They had strange scabbed rashes and phlegmy coughs and sores oozing with neglect. Their hair was matted with dirt and vermin, their eyes bloodshot and runny with infection. Many spent their days hacking and spitting, a telltale sign, according to Olive, of gaol fever.

Accompanying her father on visits to the ailing and infirm, Evangeline had learned to tuck a blanket around a feeble form or spoon broth into a slack mouth, to murmur psalms to the dying: Praise the Lord, my soul, and forget not all his benefits—who forgives all your sins and heals all your diseases, who redeems your life from the pit and crowns you with love and compassion . But she had not actually empathized. Not really. Even after leaving the home of a sickly parishioner, she would turn with thinly veiled distaste from a beggar in the street.

How young she’d been, she realized now, how easily shocked, how quick to judge.

Here she couldn’t pull the door behind her or turn away. She was no better than the sorriest wretch in the cell: no better than Olive, with her coarse laugh and rough manners, who sold her body on the street; no better than the unfortunate girl singing the lullaby, who held her infant for days until someone noticed it was dead. The most private, shameful parts of being human—the bodily fluids people spent their lives trying to contain and conceal—were what most deeply connected them: blood and bile and urine and shit and saliva and pus. She felt horrified to have been brought so low. But she also felt, for the first time, a twinge of true compassion for even the most despicable. She was one of them, after all.

The cell quieted as two guards came in to take the lifeless infant from its mother. They had to pry it from her arms as she stood humming a tuneless song, tears streaming down her cheeks.

Yes, Evangeline loathed this place, but she loathed more the vanity and naivete and willful ignorance that had landed her here.

One morning, about a fortnight after she’d been brought in, the iron door at the end of the hallway clanged open and a guard shouted: “Evangeline Stokes!”

“Here!” Struggling to be heard above the din, she pulled herself toward the cell door. She glanced down at her stained bodice, her hem weighted with filth. She smelled her own rank breath and sweat and swallowed the fear in her mouth. Still, whatever awaited her out there had to be better than what was in here.

The matron and two guards carrying truncheons appeared at the cell door. “Move aside, let ’er through,” one of the guards said, thwacking the grate with his stick as the women surged forward. When she reached the door, Evangeline was hauled out, shackled, and escorted across the street to another gray building, the Sessions House. The guards led her down a narrow set of stairs to a windowless room filled with holding cells stacked on top of each other like chicken pens, each barely large enough for one hunched adult, with slatted iron bars on either side. Once she was locked inside, and after her eyes adjusted, she could see the shapes of prisoners in other cells and hear their groans and coughs.

When a hunk of bread thumped on the floor, Evangeline jumped, banging her head on the top of her cell. An old woman in the cage beside her reached through the slats and snatched it, chortling at her alarm. “Goes to the street,” she said, pointing to the ceiling. Evangeline peered up: above the narrow aisle separating the cells into two sides was a hole. “Some people take pity.”

“Strangers throw bread down here?”

“Mostly relatives, come for a trial. Anybody here for ye?”

“No.”

Evangeline could hear her chewing. “I’d give ye some,” the woman said after a moment, “but I’m starvin’.”

“Oh—it’s all right. Thank you.”

“Your first time, I’m guessin’.”

“My only time,” Evangeline said.

The woman chortled again. “I said that once meself.”

The judge licked his lips with obvious distaste. His wig was yellowed and slightly off-kilter. A fine sprinkling of powder dusted the shoulders of his robe. The guard assigned to Evangeline had told her on the way to the courtroom that the judge had already presided over a dozen cases so far today, probably a hundred this week. Sitting on a bench in the hallway, awaiting her trial, she’d watched the accused and convicted come and go: pickpockets and laudanum addicts, prostitutes and forgers, murderers and the insane.

She stood in the dock alone. Legal counsel was for the rich. An all-male jury sat to her right, gazing at her with varying levels of indifference.

“How will you be tried?” the judge asked wearily.

“By God and by my country,” she said as instructed.

“Have you any witnesses who will vouch for your character?”

She shook her head.

“Speak, prisoner.”

“No. No witnesses.”

A barrister stood and recited the charges against her: Attempted Murder. Grand Larceny. He read from a letter that he said he had received from a Mrs. Whitstone at 22 Blenheim Road, St. John’s Wood, detailing Miss Stokes’s scandalous crimes.

The judge peered at her. “Have you anything to say for yourself, prisoner?”

Evangeline curtsied. “Well, sir. I didn’t mean to . . .” Her voice faltered. She had meant to, after all. “The ring was a gift; I didn’t steal it. My—the man who—”

Before she could continue the judge was waving his hand in the air. “I’ve heard enough.”

The jury took all of ten minutes to announce a verdict: guilty on both counts.

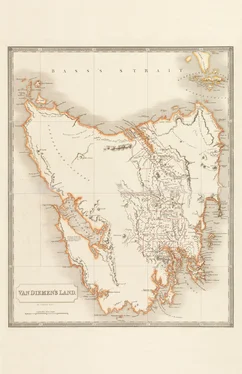

The judge lifted his gavel. “Sentenced,” he said, bringing it down with a bang. “Fourteen years transportation to the land beyond the seas.”

Evangeline clutched the wooden bar in front of her so she wouldn’t sink to her knees. Had she heard him right? Fourteen years? No one returned her gaze. The judge shuffled papers on his desk. “Summon the next prisoner,” he told his page.

“That’s it?” she asked the guard.

“That’s it. Australia. Ye’ll be a pioneer.”

She remembered Olive saying transport was a life sentence. “But . . . I can come back when my time is served?”

His laugh was devoid of pity, but not exactly unkind. “It’s the other side of the world, miss. Ye might as well be sailin’ to the sun.”

As she made her way, flanked by the guards, back to Newgate and down the dark corridor to the cells, Evangeline forced herself to square her shoulders (as best she could, chained hand and foot) and took a breath. Years ago, she’d climbed to the top of the church spire in Tunbridge Wells, where the bells were rung. As she ascended the circular stone staircase in the windowless tower, the walls narrowed and the steps became steeper; she could see a shaft of light above her head but had no idea how much farther it was to the top. Trudging upward in smaller and smaller circles, she’d feared that she might end up penned in on all sides, unable to move.

Читать дальше