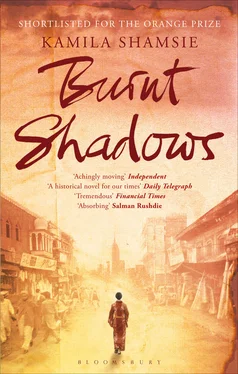

Burnt Shadows Kamila Shamsie

For Aisha Rahman and Deepak Sathe

a time to recollect

every shadow, everything the earth was losing,

a time to think of everything the earth

and I had lost, of all that I would lose,

of all that I was losing.

— Agha Shahid Ali, A Nostalgist’s Map of America

In past wars only homes burnt, but this time

Don’t be surprised if even loneliness ignites.

In past wars only bodies burnt, but this time

Don’t be surprised if even shadows ignite.

— Sahir Ludhianvi, Parchaiyaan

Once he is in the cell they unshackle him and instruct him to strip. He takes off the grey winter coat with brisk efficiency and then — as they watch, arms folded — his movements slow, fear turning his fingers clumsy on belt buckle, shirt buttons.

They wait until he is completely naked before they gather up his clothes and leave. When he is dressed again, he suspects, he will be wearing an orange jumpsuit.

The cold gleam of the steel bench makes his body shrivel. As long as it’s possible, he’ll stand.

How did it come to this , he wonders.

Nagasaki, 9 August 1945

Later, the one who survives will remember that day as grey, but on the morning of 9 August itself both the man from Berlin, Konrad Weiss, and the schoolteacher, Hiroko Tanaka, step out of their houses and notice the perfect blueness of the sky, into which white smoke blooms from the chimneys of the munitions factories.

Konrad cannot see the chimneys themselves from his home in Minamiyamate, but for months now his thoughts have frequently wandered to the factory where Hiroko Tanaka spends her days measuring the thickness of steel with micrometers, images of classrooms swooping into her thoughts the way memories of flight might enter the minds of broken-winged birds. That morning, though, as Konrad slides open the doors that form the front and back of his small wooden caretaker’s house and looks in the direction of the smoke he makes no attempt to imagine the scene unfolding wearily on the factory floor. Hiroko has a day off — a holiday, her supervisor called it, though everyone in the factory knows there is no steel left to measure. And still so many people in Nagasaki continue to think Japan will win the war. Konrad imagines conscripts sent out at night to net the clouds and release them in the morning through factory chimneys to create the illusion of industry.

He steps on to the back porch of the house. Green and brown leaves are scattered across the grass of the large property, as though the area is a battlefield in which the soldiers of warring armies have lain down, caring for nothing in death but proximity. He looks up the slope towards Azalea Manor; in the weeks since the Kagawas departed, taking their household staff with them, everything has started to look run-down. One of the window shutters is partly ajar; when the wind picks up it takes to banging against the sill. He should secure the shutter, he knows, but it comforts him to have some sound of activity issuing from the house.

Azalea Manor. In ’38 when he stepped for the first time through its sliding doors into a grand room of marble floor and Venetian fireplace it was the photographs along the wall that had captured his attention rather than the mad mixture of Japanese and European architectural styles: all taken in the grounds of Azalea Manor while some party was in progress, Europeans and Japanese mixing uncomplicatedly. He had believed the promise of the photographs and felt unaccustomedly grateful to his English brother-in-law James Burton who had told him weeks earlier that he was no longer welcome at the Burton home in Delhi with the words, ‘There’s a property in Nagasaki. Belonged to George — an eccentric bachelor uncle of mine who died there a few months ago. Some Jap keeps sending me telegrams asking what’s to be done with it. Why don’t you live there for a while? As long as you like.’ Konrad knew nothing about Nagasaki — except, to its credit, that it was not Europe and it was not where James and Ilse lived — and when he sailed into the harbour of the purple-roofed city laid out like an amphitheatre he felt he was entering a world of enchantment. Seven years later much of the enchantment remains — the glassy loveliness of frost flowers in winter, seas of blue azaleas in summer, the graceful elegance of the Euro-Japanese buildings along the seafront — but war fractures every view. Or closes off the view completely. Those who go walking in the hills have been warned against looking down towards the shipyard where the battleship Musashi is being built under such strict secrecy that heavy curtains have been constructed to block its view from all passers-by.

Functional, Hiroko Tanaka thinks, as she stands on the porch of her house in Urakami and surveys the terraced slopes, the still morning alive with the whirring of cicadas. If there were an adjective to best describe how war has changed Nagasaki, she decides, that would be it. Everything distilled or distorted into its most functional form. She walked past the vegetable patches on the slopes a few days ago and saw the earth itself furrowing in mystification: why potatoes where once there were azaleas? What prompted this falling-off of love? How to explain to the earth that it was more functional as a vegetable patch than a flower garden, just as factories were more functional than schools and boys were more functional as weapons than as humans.

An old man walks past with skin so brittle Hiroko thinks of a paper lantern with the figure of a man drawn on to it. She wonders how she looks to him, or to anyone. To Konrad. Just a gaunt figure in the drabbest of clothes like everyone else, she guesses, recalling with a smile Konrad’s admission that when he first saw her — dressed then, as now, in white shirt and grey monpe — he had wanted to paint her. Not paint a portrait of her, he added quickly. But the striking contrast she formed with the lush green of the Kagawas’ well-tended garden across which she had walked towards him ten months ago made him wish for buckets of thick, vibrant paint to pour on to her, waterfalls of colour cascading from her shoulders (rivers of blue down her shirt, pools of orange at her feet, emerald and ruby rivulets intersecting along her arms).

‘I wish you had,’ she said, taking his hand. ‘I would have seen the craziness beneath the veneer much sooner.’ He slipped his hand out of hers with a glance that mixed apology and rebuke. The military police could come upon them at any moment.

The man with the brittle skin turns to look back at her, touching his own face as if trying to locate the young man beneath the wrinkles. He has seen this neighbourhood girl — the traitor’s daughter — several times in the last few months and each time it seems that the hunger they are all inhabiting conspires to make her more beautiful: the roundness of her childhood face has melted away completely to reveal the exquisiteness of sharply angled cheekbones, a mole resting just atop one of them. But somehow she escapes all traces of harshness, particularly when, as now, her mouth curves up on one side, and a tiny crease appears just millimetres from the edge of the smile, as though marking a boundary which becomes visible only if you try to slip past it. The old man shakes his head, aware of the foolishness he is exhibiting in staring at the young woman who is entirely unaware of him, but grateful, too, for something in the world which can still prompt foolishness in him.

The metallic cries of the cicadas are upstaged by the sound of the air siren, as familiar now as the call of insects. The New Bomb! the old man thinks, and turns to hurry away to the nearest air-raid shelter, all foolishness forgotten. Hiroko, by contrast, makes a sharp sound of impatience. Already, the day is hot. In the crowded air-raid shelters of Urakami it will be unbearable — particularly under the padded air-raid hoods which she views with scepticism but has to wear if she wants to avoid lectures from the Chairman of the Neighbourhood Association about setting a poor example to the children. It is a false alarm — it is almost always a false alarm. The other cities of Japan may have suffered heavily in aerial raids, but not Nagasaki. A few weeks ago she repeated to Konrad the received wisdom that Nagasaki would be spared all serious damage because it was the most Christian of Japan’s cities, and Konrad pointed out that there were more Christians in Dresden than in Nagasaki. She has started to take the air-raid sirens a little more seriously ever since. But really, it will be so hot in the shelter. Why shouldn’t she just stay at home? It is almost certainly a false alarm.

Читать дальше