'Are they all older than you?'

'All six,' I said with a smile.

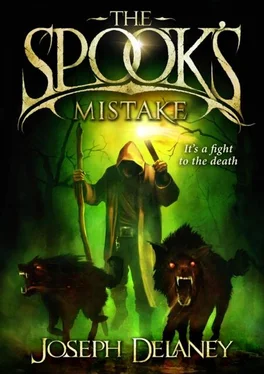

'Of course they are — what a fool I am to ask! You're the seventh son of a seventh son. The last one to gain employment and the only one fitted by birth for Bill Arkwright's trade. Do you miss them, Tom? Do you miss your family?'

I didn't speak and for a moment became choked with emotion. I felt Alice rest her hand on my arm to comfort me. It wasn't just missing my brothers that made me feel that way — it was because my dad had died the previous year and Mam had returned to her own country to fight the dark. I suddenly felt very alone.

'I can sense your sadness, Tom,' said Mr Gilbert. 'Family are very important and their loss can never be replaced. It's good to have family about you and to work alongside them as I do. I have a loyal daughter who helps me whenever I need her.'

Suddenly I shivered. Only moments earlier the sun had been far above the treetops, but now it was quickly growing dark and a thick mist was descending. All at once we were entering the city and the angular shapes of buildings quickly rose up on either side of the canal bank like threatening giants, though all was silent but for the muffled clip-clop of the horses' hooves. The canal was much wider here, with lots of recesses on the far bank where barges were moored. But there was little sign of life.

I felt the barge coming to a halt and Mr Gilbert stood up and looked down at Alice and me. His face was in darkness and I couldn't read his expression but somehow he seemed threatening.

I looked ahead and could just make out the form of his daughter, apparently draped over the leading horse. She didn't seem to be moving so she wasn't grooming it. It was almost as if she were whispering into its ear.

'That daughter of mine,' Mr Gilbert said with a sigh. 'She does so love a plump horse. Can't get enough of them. Daughter! Daughter!' he called out in a loud voice. 'There's no time for that now. You must wait until later!'

Almost immediately the horses took up the strain again, the barge glided forward and Mr Gilbert went towards the bow and sat down again.

'Don't like this, Tom,' Alice whispered in my ear. 'It don't feel right. Not right at all!'

No sooner had she spoken than I heard the fluttering of wings somewhere in the darkness overhead, followed by a plaintive, eerie cry.

'What sort of bird is that?' I asked Alice. 'I heard a cry like that just a few days ago.'

'It's a "corpsefowl", Tom. Ain't Old Gregory told you about 'em?'

'No,' I admitted.

'Well, it's something you should know about, being a spook. They're night birds and some folk think witches can shape-shift into them. But that's just a load o' nonsense. Witches do use them as familiars though. In exchange for a bit o' blood, the corpsefowl will become their eyes and ears.'

'Well, I heard one when I was looking for Morwena. D'you think it's her familiar? If so, she might be somewhere nearby. Perhaps she's moved faster than I expected. Maybe she's swimming underwater close to this barge.'

The canal narrowed, the buildings closing in on either side, as if attempting to cut us off from the thin oblong of pale sky above. They were huge warehouses, probably busy with the hustle and bustle of business during the day but now still and silent. The occasional wall-lantern sent patches of flickering light down onto the water but there were large areas of gloom and patches of intense darkness that filled me with foreboding. I agreed with Alice. I couldn't put my finger on exactly what it was but things certainly didn't feel right.

I glimpsed a dark stone arch ahead. At first I thought it was a bridge but then realized that it was the entrance to a large warehouse and the canal went straight through it. As we glided into the doorway, the horses beginning to slow, I could see that the building was vast and filled with large mounds of slate, probably brought by barge from the quarry to the north. On the wooden quayside were a number of mooring posts and a row of five huge wooden supports, which disappeared up into the darkness to hold up the roof. From each hung a lantern so that the canal and near bank were bathed in yellow light. But beyond lay the dark, threatening vastness of the warehouse.

Mr Gilbert bent towards the nearest hatch and slowly slid it back. Until that moment I hadn't noticed that it wasn't locked, something he'd once told me was vital when carrying cargo. To my surprise the hold was also filled with yellow light and I looked down to see two men sitting on a pile of slate, each nursing a lantern. Immediately I saw something to their left that started my whole body trembling and plunged me into a pit of horror and despair.

It was a dead man, the unseeing eyes staring upwards. The throat had been ripped out in a manner that reminded me of what had been done to Tooth by Morwena. But it was his identity that scared me more than the cruel horror of his murder.

The dead man was Mr Gilbert.

I looked across the open hatch at the creature who had taken the bargeman's likeness. 'If that's Mr Gilbert,' I said, 'then you must be. '

'Call me what you will, Tom. I have many names,' he replied. 'But none adequately convey my true nature. I've been misrepresented by my enemies. The difference between the words fiend and friend is merely one letter. I could easily be the latter. If you knew me better. '

With those words, I felt all the strength drain from my body. I tried to reach for my staff but my hand wouldn't obey me, and as everything grew dark, I caught a glimpse of Alice's terrified face and heard her give a wail of terror. That sound chilled me to the bone. Alice was strong. Alice was brave. For her to cry out in such a way made me feel that it was all over with us. This was the end.

Waking felt like floating up from the depths of a deep, dark ocean. I heard sounds first. The distant terrified whinnies of a horse and a man's loud, coarse laughter close by. As memories of what had happened returned, I felt panic and helplessness and I struggled to get to my feet.

I finally gave up when I'd taken in my situation. I was no longer on the barge but sitting on the wooden quay, bound tightly to one of the roof supports, my legs parallel with the canal.

By a simple act of will the Fiend had rendered me unconscious. What was worse, the strengths we'd learned to depend upon had failed us. Alice hadn't managed to sniff Morwena out. My powers as a seventh son of a seventh son had equally proven useless. Time had also seemed to pass in a way that was far from normal. One moment the sun had been shining and the city spires on the horizon; the next it had almost been dark and we'd been deep within its walls. How could anyone hope to defeat such power?

The barge was still moored at the quay and the two men, each with a long knife tucked into his leather belt, were sitting there, big steel-toed boots dangling over the edge. But the horses were no longer harnessed. One of them was lying on its side some distance away, its forelegs hanging over the water. The other was nearer, also lying down, and the girl had her arms around its neck. I thought she was trying to help it to its feet. Were the horses sick?

But there was something different about her: where previously her hair had been golden, now it was dark. How could her hair have changed colour like that? My mind was still befuddled or I would have worked out much sooner exactly what was happening. It was only when she left the horse, turned and walked towards me, her feet bare, that I began to understand.

She was cupping her hands, holding them before her strangely as she walked. Why was she doing that? And she was walking very slowly and carefully. As she drew nearer, I noticed the blood on her lips. She'd been feeding from the horse, drinking the poor animal's blood. That's what she'd been doing when I'd first glimpsed her. That's why she'd halted the barge as we journeyed south.

Читать дальше