He took the staff from me and slowly lowered it, blade first, between the two bars directly above the shelf before jabbing suddenly downwards. There was a shriek of pain and I caught a glimpse of long tangled hair and hate-filled eyes as something flung itself off the ledge into the water, making a tremendous splash.

'She'll stay down at the bottom for an hour or more now. But that certainly woke her up, didn't it?' he said with a cruel smile.

I didn't like the way he'd hurt the witch just so that I could see her better. It seemed unnecessary — not something my own master would have done.

'Mind you, she's not always that sluggish. Knowing I'd be away for quite a few days, I gave her an extra shot of salt. Put too much into the water and it'd finish her off, so you have to get your calculations right. That's how we keep her docile. Works the same way with skelts — with anything that comes out of fresh water. That's why I have a moat running around the garden. It may be shallow but it's got a very high concentration of salt. It's to stop anything getting in or out. This witch here would be dead in seconds if she managed to escape from this pit and tried to cross that moat. And it stops things from the marsh getting into the garden.

'Anyway, Master Ward, I'm not as soft-hearted as Mr Gregory. He keeps live witches in pits because he can't bring himself to finish them off, whereas I do it just to punish them. They serve one year in a pit for every life they've taken — two years for the life of a child. Then I fish them out and kill them. Now, let's see if we can catch a glimpse of that skelt I told you I'd captured near the canal. '

He led the way to another pit almost twice the size of the first. It was similarly covered with iron bars but there were many more of them and they were far closer together. Here there was no mud shelf, just an expanse of dirty water. I had a feeling that it was very deep. Arkwright stared down at the water and shook his head.

'Looks like it's lurking near the bottom. Still docile after the big dose of salt I tipped into the water. It's best to let sleeping skelts lie. There'll be plenty of opportunity to see it before your six months is up. Right, we'll take a walk around the garden now. '

'Does she have a name?' I asked, nodding down at the witch pit as we passed.

Arkwright came to a halt, looked at me and shook his head. There were several expressions flickering across his face, none of them good. Clearly he thought I'd said something really stupid.

'She's just a common water witch,' he said, his voice scathing. 'Whatever she calls herself, I neither know nor care! Don't ask foolish questions!'

I was suddenly angry and felt my face redden. 'It can be useful to know a witch's name!' I snapped. 'Mr Gregory keeps a record of all the witches that he's either heard of or encountered personally.'

Arkwright pushed his face very close to mine so that I could smell his sour breath. 'You're not at Chipenden now, boy. For the present I'm your master and you'll do things my way. And if you ever speak to me in that tone of voice again, I'll beat you to within an inch of your life! Do I make myself clear?'

I bit my lip to stop myself answering back, then nodded and looked down at my boots. Why had I spoken out of turn like that? Well, one reason was that I thought he was wrong. Another was that I didn't like the tone of voice he'd used to speak to me. But I shouldn't have let my anger show. After all, my master had told me that Arkwright did things differently and that I would have to adapt to his ways.

'Follow me, Master Ward,' Arkwright said, his voice softer, 'and I'll show you the garden. '

Rather than leading the way back up the steps to the front room, Arkwright walked back towards the waterwheel. At first I thought he was going to squeeze past it but then I noticed a narrow door to the left, which he unlocked. We strode out into the garden, I saw that the mist had lifted but still lingered in the distance, beyond the trees. We made a complete inner circuit of the moat; from time to time Arkwright halted to point things out.

'That's Monastery Marsh,' he said, jabbing his finger towards the south-west. 'And beyond it is Monks' Hill. Never try to cross that marsh alone — or at least not until you know your way around or have studied a map. Beyond the marsh, more directly to the west, is a high earthen bank that holds back the tide from the bay.' I looked around, taking in everything he said. 'Now,' he continued, 'I want you to meet somebody else. '

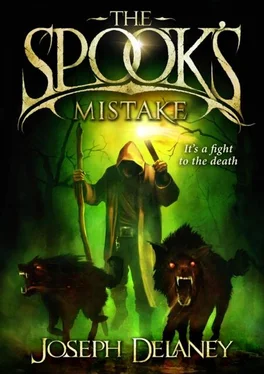

That said, he put two fingers in his mouth and let out a long, piercing whistle. He repeated it, and almost immediately, from the direction of the marsh, I heard something running towards us. Two large wolfhounds bounded into view, both leaping the moat with ease. I was used to farm dogs but these animals had a savage air about them and seemed to be heading directly towards me. They had more wolf in them than dog, and had I been alone, I'm sure they'd have pulled me to the ground in seconds. One was a dirty looking grey with streaks of black; its companion was as black as coal but for a dash of grey at the tip of its tail. Their jaws gaped wide, teeth ready to bite.

But at Arkwright's command, 'Down!' they halted immediately, sat back upon their haunches and gazed up at their master, tongues lolling from their open mouths.

'The black one's the bitch,' Arkwright said. 'Her name is Claw. Don't turn your back on her — she's dangerous. And this is Tooth,' he added, pointing to the grey. 'Better temperament, but they're both working dogs, not pets. They obey me because I feed 'em well and they know not to cross me. The only affection they get is from each other. They're a pair all right. Inseparable.'

'I lived on a farm. We had working dogs,' I told him.

'Did you now? Well, you'll have an inkling of what I mean. No room for sentiment with a working dog. Treat them fairly, feed them well, but they have to earn their keep in return. I'm afraid there's little in common between farm dogs and these two though. At night they're usually kept chained up close to the house and trained to bark if anything approaches. During the day they hunt rabbits and hares out on the edge of marsh and keep watch for anything that might threaten the house.

'But when I go out on a job, they come with me. Once they get a scent they never let it go. They hunt down whatever I set 'em on. And if it proves necessary, on my command they kill too. As I said, they work hard and feed well. When I kill a witch, they get something extra in their diet. I cut out her heart and throw it to them. That, as your master will already have told you, stops her from coming back to this world in another body and also from using her dead one to scratch her way to the surface. That's why I don't keep dead witches. It saves time and space.'

There was a ruthless edge to Arkwright — he certainly wasn't a man to cross. As we turned to walk back to the house, the dogs following at our heels, I happened to glance up and saw something that surprised me. Two separate columns of smoke were curling upwards from the roof of the mill. One must be from the stove in the kitchen. But where was the second fire? I wondered if it was coming from the locked room I'd been warned about. Was there something or someone up there Arkwright didn't want me to see? Then I remembered about the unquiet dead that he allowed the run of his house. I knew he was a man who was quick to anger and I was pretty sure that he wouldn't want me prying, but I was feeling very curious.

'Mr Arkwright,' I began politely, 'could I ask you a question?'

'That's why you're here, Master Ward. '

'It's about what you put in the note you left me. Why do you allow the dead to walk in your house?'

Again an angry expression flickered across his face. 'The dead here are family. My family, Master Ward. And it's not something I wish to discuss with you or anyone else, so you'll have to contain your curiosity. When you get back to Mr Gregory, ask him. He knows something about it, and no doubt he'll tell you. But I don't want to hear another word on the matter. Do you understand? It's something I just don't talk about.'

Читать дальше