Stephen Fry - The Ode Less Travelled - Unlocking The Poet Within

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Stephen Fry - The Ode Less Travelled - Unlocking The Poet Within» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The references to flesh, love and the transience of youth make me feel this does qualify. I have no evidence that Auden thought of it as anacreontic and I may be wrong. Certainly one feels that not since Shakespeare’s earlier sonnets has any youth had such gorgeous verse lavished upon him. I dare say both the subjects proved unworthy (the poets knew that, naturally) and both boys are certainly dead–the grave has proved the child ephemeral. Ars longa, vita brevis : 9life is short, but art is long.

VI

Closed Forms

Villanelle–sestina–ballade, ballade redoublé

Certain closed forms, such as those we are going to have fun with now, seem demanding enough in their structures and patterning to require some of the qualities needed for so-doku and crosswords. It takes a very special kind of poetic skill to master the form and produce verse of a quality that raises the end result above the level of mere cunningly wrought curiosity. They are the poetic equivalent of those intricately carved Chinese étuis that have an inexplicable ivory ball inside them.

T HE V ILLANELLE Kitchen Villanelle How rare it is when things go rightWhen days go by without a slipAnd don’t go wrong, as well they might.The smallest triumphs cause delight–The kitchen’s clean, the taps don’t drip,How rare it is when things go right.Your ice cream freezes overnight,Your jellies set, your pancakes flipAnd don’t go wrong, as well they mightWhen life’s against you, and you fightTo keep a stiffer upper lip.How rare it is when things go right,The oven works, the gas rings light,Gravies thicken, potatoes chipAnd don’t go wrong as well they might.Such pleasures don’t endure, so biteThe grapes of fortune to the pip.How rare it is when things go rightAnd don’t go wrong as well they might.

The villanelle is the reason I am writing this book. Not that lame example, but the existence of the form itself.

Let me tell you how it happened. I was in conversation with a friend of mine about six months ago and the talk turned to poetry. I commented on the extraordinary resilience and power of ancient forms, citing the villanelle. 10

‘What’s a villanelle?’

‘Well, it’s a pastoral Italian form from the sixteenth century written in six three-line stanzas where the first line of the first stanza is used as a refrain to end the second and fourth stanzas and the last line of the first stanza is repeated as the last line of the third, fifth and sixth,’ I replied with fluent ease.

You have never heard such a snort of derision in your life.

‘ What ? You have got to be kidding!’

I retreated into a resentful silence, wrapped in my own thoughts, while this friend ranted on about the constraint and absurdity of writing modern poetry in a form dictated by some medieval Italian shepherd. Inspiration suddenly hit me. I vaguely remembered that I had once heard this friend express great admiration for a certain poet.

‘Who’s your favourite twentieth-century poet?’ I asked nonchalantly.

Many were mentioned. Yeats, Eliot, Larkin, Hughes, Heaney, Dylan Thomas.

‘And your favourite Dylan Thomas poem?’

‘It’s called “Do not go gentle into that good night”.’

‘Ah,’ I said. ‘Does it have any, er, what you might call form particularly? Does it rhyme, for instance?’

He scratched his head. ‘Well, yeah it does rhyme I think. “Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” and all that. But it’s like–modern. You know, Dylan Thomas. Modern . No crap about it.’

‘Would you be surprised to know’, I said, trying to keep a note of ringing triumph from my voice, ‘that “Do not go gentle into that good night” is a straight-down-the-line, solid gold, one hundred per cent perfect, unadulterated villanelle ?’

‘Bollocks!’ he said. ‘It’s modern. It’s free.’

The argument was not settled until we had found a copy of the poem and my friend had been forced to concede that I was right. ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’ is indeed a perfect villanelle, following all the rules of this venerable form with the greatest precision. That my friend could recall it only as a ‘modern’ poem with a couple of memorable rhyming refrains is a testament both to Thomas’s unforced artistry and to the resilience and adaptability of the form itself: six three-line stanzas or tercets , 11each alternating the refrains introduced in the first stanza and concluding with them in couplet form:Do not go gentle into that good night,Old age should burn and rave at close of day;Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Though wise men at their end know dark is right,Because their words had forked no lightning theyDo not go gentle into that good night.Good men, the last wave by, crying how brightTheir frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,Do not go gentle into that good night.Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sightBlind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,Rage, rage against the dying of the light.And you, my father, there on the sad height,Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray.Do not go gentle into that good night.Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

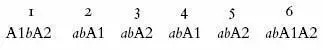

The conventional way to render the villanelle’s plan is to call the first refrain (‘Do not go gentle’) A1 and the second refrain (‘Rage, rage…’)A2. These two rhyme with each other (which is why they share the letter): the second line (‘Old age should burn’) establishes the b rhyme which is kept up in the middle line of every stanza.

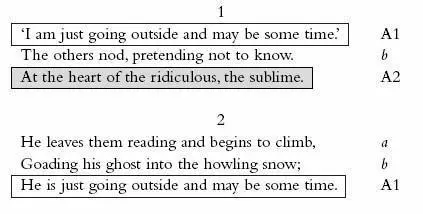

Much easier to grasp in action than in code. I have boxed and shaded the refrains here in Derek Mahon’s villanelle ‘Antarctica’. (I have also numbered the line and stanzas, which of course Mahon did not do):

3

I hope you can see from this layout that the form is actually not as convoluted as it sounds. Describing how a villanelle works is a great deal more linguistically challenging than writing one. Mahon, by the way, as is permissible, has slightly altered the refrain line, in his case turning the direct speech of the first refrain. There are no rules as to metre or length of measure, but the rhyming is important. Slant-rhyme versions exist but for my money the shape, the revolving gavotte of the refrains and their final coupling, is compromised by partial rhyming. The form is thought to have evolved from Sicilian round songs, of the ‘London Bridge is falling down’ variety. In the anthologies you will find villanelles culled from the era of their invention, the sixteenth century, especially translations of the work of the man who really got the form going, the French poet Jean Passerat: after these examples there seems to be a notable lacuna until the late nineteenth century. Oscar Wilde wrote ‘Theocritus’, a rather mannered neo-classical venture–‘O singer of Persephone!/Dost thou remember Sicily?’ (I think it best to refer to villanelles by their refrain lines), while Ernest Dowson, Wilde’s friend and fellow Yellow Book contributor, came up with the ‘Villanelle of His Lady’s Treasures’ which is a much bouncier attempt, very Tudor in flavour: ‘I took her dainty eyes as well/And so I made a Villanelle.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking The Poet Within» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.