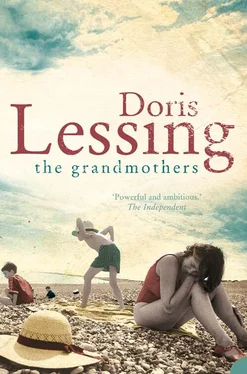

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He comforted her, she him, but she knew that something was biting at his heart she was not going to know about. How old? ‘Nearly six - five years, eleven months, ten days.’

A wedding, restricted by post-war shortages.

They did everything right. Every Sunday they went to lunch with James’s parents, and they visited her parents, who lived far away, in Scotland, for holidays. They had a child, a girl, named Deirdre, because of James Stephens’ poem about the Irish queen. Helen liked this poem but joked that it was asking a lot for their little girl to be as beautiful as that. But Deirdre was pretty enough.

Eight years after the war ended James told Helen he was going to South Africa, He could have gone before, but that would have meant a ship, and he would never set foot on a ship again - never. It had to be the air, and when they could afford it. She knew there was no point in minding. He never mentioned Ins other child unless she asked, but then he promptly told her, ‘He is seven years, three months, ten days,’ or whatever it was. Sometimes she checked just to see if that invisible calendar was still running there, in him, marking . , . but she did not know what. This was not merely a question of a child’s exact age.

James’s plane descended at Khartoum, Lake Victoria, Johannesburg, with leisurely time at each for refuelling, restocking. This cumbersome trip seemed to him miraculous, when he remembered that other voyage. Then Cape Town, spread out over its hills, surrounded by sea. He found a modest hotel from where he could look down at the sea, the now innocent sea, full of ships, one being a passenger liner sparkling with new paint. Then he put a thick paper parcel under his arm and walked up through streets he remembered not at all to what he did remember, the two ample houses side by side in a street of gardened houses. On the gate where there should have been the name Wright, was the unknown Williams. The gate post for next door was still Stubbs. I le retreated across the street to stand under an oak, and he looked for a long time at Daphne’s house, which in his memory lived as zones of intensity, the little room he had been given, Daphne’s bedroom, and the stoep, all else being dark. On to the verandah - the stoep - came an old woman, with a book. She sat in a grass chair, put on dark glasses, and gazed down at the sea. There was no sign of other life. Then he as carefully examined Betty’s house, of which he remembered only the garden. He could see movement through the windows that opened off the verandah. A maid? A black woman with a white headscarf. But he couldn’t see her properly He moved across the street, cautiously pushed open the gate, and stood under the tree which he remembered spreading over trestles, full of food and drink, and a crush of people - soldiers. The companion tree in the other garden would live in his mind for ever because of the two beautiful young women, one dark, one fair, standing in grass, under it, wearing flowery wrappers.

Someone had come on to the Stubbs’s verandah. A tall woman. She shaded her eyes to peer at him and came slowly down the steps towards him. He did not know her. She stopped a few paces off, let her hand fall, and looked forward to have a good look. Then she straightened and stood, arms loose by her side, in a pose it did seem he remembered. A tall thin woman. She wore a short well-fitting blue and yellow dress in small geometrical patterns, with a narrow gold-edged belt, and some little gold beads. Her face was thin and sunburned and her dark hair was waved in neat ridges. On one thin wrist hung a gold bangle. Yes, now he knew - it was the bangle -this was Betty. She spoke: ‘What are you doing here?’

This question seemed to him so absurd he only smiled. He thought that the stern face - she was like a headmistress, or the manager of something - almost smiled in response, but then she frowned.

‘James - it is James? - then you must go away.’

‘Where is Daphne?’

At this there was a pause, and then a quick expulsion of breath - the sigh of someone who has been holding it. ‘She’s not here.’

‘Where is she?’

She came a step closer. He was thinking, already afflicted with anguish, that this tall dry uncharming woman had been that lovely creature he remembered as all dark flowing hair and loose soft gowns.

‘I must see Daphne.’

‘I told you, she’s not here.’

‘Where is she?’

‘She doesn’t live here now.’

‘I can see that. It’s on the gate. Is she in Cape Town?’

A tiny hesitation. ‘No.’

So, she was lying. ‘I could find out where she lives/This was not a threat, but a reminder to himself that he was not dependent on her for information.

She was agitated now, she actually raised those brown thin forearms, pressing the long dry hands to her chest. ‘James,’ she said, urgent, appealing, afraid. ‘You mustn’t do this. Why are you doing this? Do you want to ruin her life? Do you want to break up her marriage? She has three children now.’

‘One of them is mine.’

She did not seem inclined to dispute it. ‘You just turn up like this, turn up, as if it’s nothing, you just arrive and …’

‘I want to see my son. He’s going to have a birthday, his twelfth birthday’ And he recited his son’s exact age, years, months, days.

She closed her eyes. Her lids were white against the tan of her face. She was breathing deep: she was shocked. He waited until she opened them. Betty had deep brown eyes, he remembered, brown kind eyes in a smiling lightly tanned face: he had thought of her as ‘a nut brown maid’. Well, there were the eyes, and there were tears in them. Not unkind, no, they were still kind.

‘James, do you want to ruin Daphne’s life?’

‘No. I love her.’

‘That’s what you’ll do if you go on with this.’

‘I want my son.’

‘But you must see …’ She stopped. That sigh again, almost a gasp. Oh, yes, she was frightened all right. But she was on guard, fighting: she was protecting her friend.

‘Do you still see her?’

‘Of course. She’s my best pal.’

He produced his great lump of parcel: the letters. He held it out.

‘What is that?’

‘My letters. I’ve written to her, you see. I’ve always written to her. In the war there was the censorship. Then I didn’t want to cause trouble. So I brought them.’

She didn’t take them from him.

He stood obdurately there, holding out the parcel: the force of his demand caused her hand to come towards it. She hesitated, then took it. ‘Will you give them to her?’

‘I suppose so.’

‘Do you promise?’

They stared at each other, then her gaze lowered to the parcel.

‘Yes, I promise.’

‘My son,’ he urged. ‘It’s my son. I think of him … yes, all the time. Perhaps he will come and visit us in England?’

‘You’re mad. Yes, you’re mad. Yes, you are.’

But she held the parcel against her chest.

‘You’ve promised,’ he said.

She backed a couple of steps, then turned and ran for it, but over her shoulder she said, ‘Wait, just wait there.’

He waited. He did not look at all at the verandah where the old woman now read her book, the dark glasses pushed up to her forehead.

After a good twenty minutes, the maid emerged from inside the house, white apron, white headscarf, a worried face. She stopped in front of him and held out a large envelope. There she stood while he tore open the envelope. She was peering to see what she could. From inside the house came a voice from the invisible Betty. ‘Evelyn, Evelyn, I want you.’

Taking her time, her eyes never leaving the envelope, the maid turned and went off, sending back slow thoughtful looks over her shoulder.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.