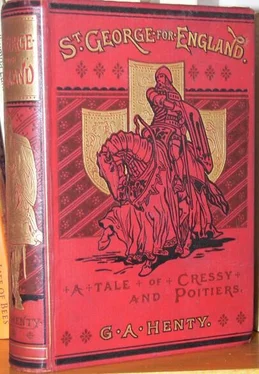

G. Henty - St. George for England - A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «G. Henty - St. George for England - A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

History has no record of so vast a slaughter by so small a body of men. This terrific punishment put a summary end to the Jacquerie. Already in other parts several bodies had been defeated, and their principal leader, Caillet, with three thousand of his followers, slain near Clermont. But the defeat at Meaux was the crushing blow which put an end to the insurrection.

On their return to the town the knights executed a number of the burghers who had joined the peasants, and the greater part of the town was burned to the ground as a punishment for having opened the gates to the peasants and united with them.

The knights and ladies then started for Paris. On nearing the city they found that it was threatened by the forces of the dauphin. Marcel had strongly fortified the town, and with his ally, the infamous King of Navarre, bade defiance to the royal power. However, the excesses of the demagogue had aroused against him the feeling of all the better class of the inhabitants. The King of Navarre, who was ready at all times to break his oath and betray his companions, marched his army out of the town and took up a position outside the walls. He then secretly negotiated peace with the Duke of Normandy, by which he agreed to yield to their fate Marcel and twelve of the most obnoxious burghers, while at the same time he persuaded Marcel that he was still attached to his interest. Marcel, however, was able to bid higher than the Duke of Normandy, and he entered into a new treaty with the treacherous king, by which he stipulated to deliver the city into his hands during the night. Every one within the walls, except the partisans of Marcel, upon whose doors a mark was to be placed, were to be put to death indiscriminately, and the King of Navarre was to be proclaimed King of France.

Fortunately Pepin des Essarts and John de Charny, two loyal knights who were in Paris, obtained information of a few minutes before the time appointed for its execution. Arming themselves instantly, and collecting a few followers, they rushed to the houses of the chief conspirators, but found them empty, Marcel and his companions having already gone to the gates. Passing by the hotel-de-ville, the knights entered, snatched down the royal banner which was kept there, and unfurling it mounted their horses and rode through the streets, calling all men to arms. They reached the Port St. Antoine just at the moment when Marcel was in the act of opening it in order to give admission to the Navarrese. When he heard the shouts he tried with his friends to make his way into the bastile, but his retreat was intercepted, and a severe and bloody struggle took place between the two parties. Stephen Marcel, however, was himself slain by Sir John de Charny, and almost all his principal companions fell with him. The inhabitants then threw open their gates and the Duke of Normandy entered.

Walter Somers had, with his companions, joined the army of the duke and placed his sword at his disposal; but when the French prince entered Paris without the necessity of fighting, he took leave of him, and with the captal returned to England. Rare, indeed, were the jewels which Walter brought home to his wife, for the three hundred noble ladies rescued at Meaux from dishonor and death had insisted upon bestowing tokens of their regard and gratitude upon the rescuers, and as many of them belonged to the richest as well as the noblest families in France, the presents which Walter thus received from the grateful ladies were of immense value.

He was welcomed by the king and Prince of Wales with great honor, for the battle at Meaux had excited the admiration and astonishment of all Europe. The Jacquerie was considered as a common danger in all civilized countries; for if successful it might have spread far beyond the boundaries of France, and constituted a danger to chivalry, and indeed to society universally.

Thus King Edward gave the highest marks of his satisfaction to the captal and Walter, added considerable grants of land to the estates of the latter, and raised him to the dignity of Baron Somers of Westerham.

It has always been a matter of wonder that King Edward did not take advantage of the utter state of confusion and anarchy which prevailed in France to complete his conquest of that country, which there is no reasonable doubt he could have effected with ease. Civil war and strife prevailed throughout France; famine devastated it; and without leaders or concord, dispirited and impoverished by defeat, France could have offered no resistance to such an army as England could have placed in the field. The only probable supposition is that at heart he doubted whether the acquisition of the crown of France was really desirable, or whether it could be permanently maintained should it be gained. To the monarch of a county prosperous, flourishing, and contented the object of admiration throughout Europe, the union with distracted and divided France could be of no benefit. Of military glory he had gained enough to content any man, and some of the richest provinces of France were already his. Therefore it may well be believed that, feeling secure very many years must elapse before France could again become dangerous, he was well content to let matters continue as they were.

King John still remained a prisoner in his hands, for the princes and nobles of France were too much engaged in broils and civil wars to think of raising the money for his ransom, and Languedoc was the only province of France which made any effort whatever toward so doing. War still raged between the dauphin and the King of Navarre.

At the conclusion of the two years' truce Edward, with the most splendidly equipped army which had ever left England, marched through the length and breadth of France. Nowhere did he meet with any resistance in the field. He marched under the walls of Paris, but took no steps to lay siege to that city, which would have fallen an easy prey to his army had he chosen to capture it. That he did not do so is another proof that he had no desire to add France to the possessions of the English crown. At length, by the efforts of the pope, a peace was agreed upon, by which France yielded all Aquitaine and the town of Calais to England as an absolute possession, and not as a fief of the crown of France; while the English king surrendered all his captures in Normandy and Brittany and abandoned his claim to the crown of France. With great efforts the French raised a portion of the ransom demanded for the king, and John returned to France after four years of captivity.

At the commencement of 1363 Edward the Black Prince was named Prince of Aquitaine, and that province was bestowed upon him as a gift by the king, subject only to liege homage and an annual tribute of one ounce of gold. The prince took with him to his new possessions many of the knights and nobles who had served with him, and offered to Walter a high post in the government of the province if he would accompany him. This Walter begged to be excused from doing. Two girls had now been added to his family, and he was unwilling to leave his happy home unless the needs of war called him to the prince's side. He therefore remained quietly at home.

When King John returned to France, four of the French princes of the blood-royal had been given as hostages for the fulfillment of the treaty of Bretigny. They were permitted to reside at Calais and were at liberty to move about as they would, and even to absent themselves from the town for three days at a time whensoever they might choose. The Duke of Anjou, the king's second son, basely took advantage of this liberty to escape, in direct violation of his oath. The other hostages followed his example.

King John, himself the soul of honor, was intensely mortified at this breach of faith on the part of his sons, and after calling together the States-general at Amiens to obtain the subsidies necessary for paying the remaining portion of his ransom, he himself, with a train of two hundred officers and their followers, crossed to England to make excuses to Edward for the treachery of the princes. Some historians represent the visit as a voluntary returning into captivity; but this was not so. The English king had accepted the hostages in his place and was responsible for their safe-keeping, and had no claim upon the French monarch because they had taken advantage of the excess of confidence with which they had been treated. That the coming of the French king was not in any way regarded as a return into captivity is shown by the fact that he was before starting furnished by Edward with letters of safe-conduct, by which his secure and unobstructed return to his own country was expressly stipulated, and he was received by Edward as an honored guest and friend, and his coming was regarded as an honor and an occasion for festivity by all England.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.