Allison Bartlett - The Man Who Loved Books Too Much - The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Allison Bartlett - The Man Who Loved Books Too Much - The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

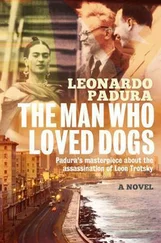

- Название:The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, a compelling narrative set within the strange and genteel world of rare-book collecting: the true story of an infamous book thief, his victims, and the man determined to catch him. Rare-book theft is even more widespread than fine-art theft. Most thieves, of course, steal for profit. John Charles Gilkey steals purely for the love of books. In an attempt to understand him better, journalist Allison Hoover Bartlett plunged herself into the world of book lust and discovered just how dangerous it can be.

Gilkey is an obsessed, unrepentant book thief who has stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars? worth of rare books from book fairs, stores, and libraries around the country. Ken Sanders is the self-appointed ?bibliodick? (book dealer with a penchant for detective work) driven to catch him. Bartlett befriended both outlandish characters and found herself caught in the middle of efforts to recover hidden treasure. With a mixture of suspense, insight, and humor, she has woven this entertaining cat-and-mouse chase into a narrative that not only reveals exactly how Gilkey pulled off his dirtiest crimes, where he stashed the loot, and how Sanders ultimately caught him but also explores the romance of books, the lure to collect them, and the temptation to steal them. Immersing the reader in a rich, wide world of literary obsession, Bartlett looks at the history of book passion, collection, and theft through the ages, to examine the craving that makes some people willing to stop at nothing to possess the books they love.

From Publishers Weekly

Bartlett delves into the world of rare books and those who collect—and steal—them with mixed results. On one end of the spectrum is Salt Lake City book dealer Ken Sanders, whose friends refer to him as a book detective, or Bibliodick. On the other end is John Gilkey, who has stolen over $100,000 worth of rare volumes, mostly in California. A lifelong book lover, Gilkey's passion for rare texts always exceeded his income, and he began using stolen credit card numbers to purchase, among others, first editions of Beatrix Potter and Mark Twain from reputable dealers. Sanders, the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association's security chair, began compiling complaints from ripped-off dealers and became obsessed with bringing Gilkey to justice. Bartlett's journalistic position is enviable: both men provided her almost unfettered access to their respective worlds. Gilkey recounted his past triumphs in great detail, while Bartlett's interactions with the unrepentant, selfish but oddly charming Gilkey are revealing (her original article about himself appeared in

). Here, however, she struggles to weave it all into a cohesive narrative. From Bookmarks Magazine

Bibliophiles themselves, reviewers clearly wanted to like

. The degree to which they actually did depended on how they viewed Bartlett's authorial choices. Several critics were drawn in by Bartlett's own involvement in the story, as in the scene where she follows Gilkey through a bookstore he once robbed. But others found this style lazy, boring, or overly "literary," and wished Bartlett would just get out of the way. A few also thought that Bartlett ascribed unbelievable motives to Gilkey. But reviewers' critiques reveal that even those unimpressed with Bartlett's style found the book an entertaining true-crime story.