Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Eleventh Day

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Eleventh Day: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Eleventh Day»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Eleventh Day — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Eleventh Day», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The following day, CIA officers went to the White House for a meeting with a select group of top-level National Security Council members. Attendees discussed both the lack of inside information and how essential it was to achieve “penetrations.” Many “unilateral avenues” and “creative attempts” were subsequently to be tried. Material on those attempts in the document has been entirely redacted.

President Clinton himself aside, the senior White House official to whom the CIA reported at that time was National Security Adviser Sandy Berger. After 9/11, while preparing to testify before official inquiries into the attacks, Berger was to commit a crime that destroyed his shining reputation, a folly so bizarre—for a man of his stature—as to be unbelievable were it not true.

On four occasions in 2002 and 2003, Berger would make his way to the National Archives in Washington, the repository of the nation’s most venerated documents—including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. This trusted official, alumnus of Cornell and Harvard, former lawyer and aide to public officials, a former deputy director of policy planning at State, had crowned his career by becoming national security adviser during President Clinton’s second term.

It was at Clinton’s request, and in his capacity as one of the very few people allowed access to the former administration’s most secret documents, that Berger went to the Archives to review selected files. Given his seniority, he was received with special courtesy and under rather less than the usual stringent security conditions. All the more astounding then that on his third visit a staff member “saw Mr. Berger bent down, fiddling with something that could have been paper, around his ankle.”

Under cover of asking for privacy to make phone calls, or in the course of uncommonly frequent visits to the lavatory, the former national security adviser was purloining top secret documents, smuggling them out of the building hidden in his clothing, and taking them home. He was caught doing so, publicly exposed, forced to resign from his senior post with the 2004 Democratic campaign for the presidency, charged with taking classified documents, and—a year later—fined $50,000 and sentenced to one hundred hours of community service.

What had possessed Berger? What seemed so compromising to himself or to the Clinton administration—or so essential to be hidden from 9/11 investigators—as to drive him to risk national disgrace?

What is known is that Berger took no fewer than five copies of the Millennium After Action Review, or MAAR, a thirteen-page set of recommendations that had been written in early 2000, focused mostly on countering al Qaeda activity inside the United States. While the MAAR is still classified, it seems somewhat unlikely that it is the item that Berger deemed potential dynamite. It may have been handwritten notes on the copies that he thought potentially explosive, former 9/11 Commission senior counsel John Farmer has surmised. That would account for the former official’s apparently frantic search for additional copies.

The National Archives inspector general and others worried about what other documents Berger may have removed from the Archives. Short of a further admission on his part, the director of the Archives’ presidential documents staff conceded, we shall never know. Whatever he took, Farmer pointed out, it made him appear “desperate to prevent the public from seeing certain papers.”

“What information could be so embarrassing,” House Speaker Dennis Hastert asked, “that a man with decades of experience in handling classified documents would risk being caught pilfering our nation’s most sensitive secrets? … Was this a bungled attempt to rewrite history and keep critical information from the 9/11 Commission?”

The question is all the more relevant when one notes that, so far as one can tell, Berger’s focus was on the period right after the CIA’s resolve to “penetrate” bin Laden’s terrorist apparatus, or “recruit” inside it, an aspiration followed in rapid order by the discovery of Khalid al-Mihdhar’s U.S. entry visa—and the highly suspect failure to share that information with the State Department and the FBI.

THOUGH FRAGMENTARY, there are pointers suggesting that the CIA did not promptly drop its coverage of Mihdhar. On January 5, 2000—the day of the discovery of Mihdhar’s visa, and in the same cable that claimed the FBI had been notified—desk officer “Michelle” noted that “we need to continue the effort to identify these travelers and their activities.” As late as February, moreover, a CIA message noted that the Agency was still engaged in an investigation “to determine what the subject is up to.”

Mihdhar was to tell KSM, according to the CIA account of KSM’s interrogation, that he and Hazmi “believed they were surveilled from Thailand to the U.S.” KSM seems to have taken this possibility seriously—sufficiently so, the CIA summary continues, that he “began having doubts whether the two would be able to fulfil their mission.” Later, in 2001, two other members of the hijack team sent word that they thought they, too, had been tailed on a journey within the United States.

The hijackers may have imagined they were being followed. Given their mission, it would have been a natural enough fear. There is another relevant lead, though, that has more substance.

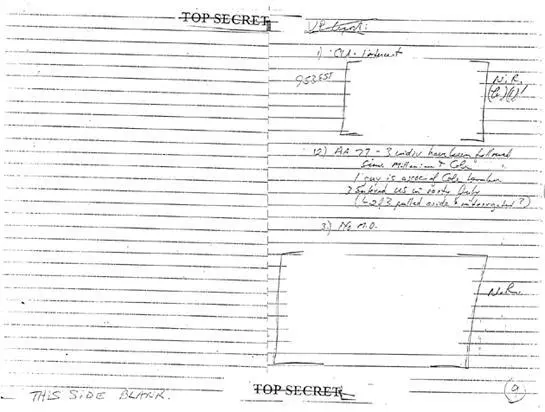

In the early afternoon of September 11, the senior aide to Defense Secretary Rumsfeld penned a very curious handwritten note. Written by Deputy Under Secretary Stephen Cambone at 2:40 P.M., following a phone call between Rumsfeld and Tenet, it appears in a record of the day’s events that was obtained in 2006 under the Freedom of Information Act.

The note reads:

AA 77–3 indiv have been followed since Millennium & Cole

1 guy is assoc of Cole bomber

3 entered US in early July

(2 of 3 pulled aside and interrogated?)

Though somewhat garbled, probably due to the rush of events in those hectic hours, the details more or less fit. Mihdhar, Hazmi, and Hazmi’s brother were hijackers aboard American Flight 77, the airliner that was flown into the Pentagon. Mihdhar had been an associate of USS Cole planner Attash, the most significant of the fellow terrorists with whom he met in Kuala Lumpur. Mihdhar, certainly, had entered the United States—for the second time, after months back in the Middle East—in “early July,” on July 4.

Cambone’s note on three individuals having “been followed” could be interpreted in two ways. Had Tenet meant during his conversation with Secretary Rumsfeld merely to convey the fact that three of the terrorists had at an earlier point come to the notice of the intelligence community? Or had he—conceivably—meant what the note says he said, that the terrorists’ movements had indeed been monitored?

Was it Tenet’s knowledge of some intelligence operation that had targeted Mihdhar and Hazmi—whether in the shape of monitoring them or attempting to recruit them—that led to the director’s flash of recognition and his “Oh, Jesus” exclamation on seeing their names on the Flight 77 manifest?

If an operation had been attempted, contrary to the rules that govern CIA activities, to whom was it entrusted? To try to answer that question is to fumble in the dark. There are pointers, though, in the evidence as to whether any foreign nation-state—other than Afghanistan, where the Taliban played host to bin Laden—had responsibility at any level for the 9/11 attacks.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Eleventh Day» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.