Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Eleventh Day

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Eleventh Day: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Eleventh Day»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Eleventh Day — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Eleventh Day», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“James,” the inspector general noted, refused to be interviewed.

The inspector general was given access to “Michelle,” the desk officer who had written flatly that Mihdhar’s passport and visa had been passed to the FBI. She prevaricated, however, saying she could not remember how she knew that fact. Her boss, Tom Wilshire, the deputy chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit, said that for his part he had no knowledge of the “Michelle” cable. He “did not know whether the information had been passed to the FBI.”

Other documents indicate that the opposite was the case, that Wilshire had deliberately ensured that the information would not reach the FBI. This emerged with the inspector general’s discovery of a draft cable—one prepared but never sent—by an FBI agent on attachment to the CIA’s bin Laden unit.

Having had sight of a CIA cable noting that Mihdhar possessed a U.S. visa, Agent Doug Miller had responded swiftly by drafting a Central Intelligence Report, or CIR, addressed to the Bureau’s bin Laden unit and its New York field office. Had the CIR then been sent, the FBI would have learned promptly of Mihdhar’s entry visa.

As regulations required, Agent Miller first submitted the draft to CIA colleagues for clearance. Hours later, though, he received a note from “Michelle” stating: “pls hold off on CIR for now per [Wilshire].”

Perplexed and angry, Miller consulted with Mark Rossini, a fellow FBI agent who was also on attachment to the CIA unit. “Doug came to me and said, ‘What the fuck?,’ ” Rossini recalled. “So the next day I went to [Wilshire’s deputy, identity uncertain] and said, ‘What’s with Doug’s cable? You’ve got to tell the Bureau about this.’ She put her hand on her hip and said, ‘Look, the next attack is going to happen in South East Asia—it’s not the FBI’s jurisdiction. When we want the FBI to know about it, we’ll let them know.’ ”

After eight days, when clearance to send the message still had not come, Agent Miller submitted the draft again directly to CIA deputy unit chief Wilshire along with a note asking: “Is this a no go or should I remake it in some way?” According to the CIA, it was “unable to locate any response to this e-mail.”

Neither Miller nor Rossini was interviewed by 9/11 Commission staff. Wilshire was questioned, the authors established, but the report of his interview is redacted in its entirety.

In July 2001, by which time he had been seconded to the FBI’s bin Laden unit, Wilshire proposed to CIA colleagues that the fact that Mihdhar had a U.S. entry visa should be shared with the FBI. It never happened.

Following a subsequent series of nods and winks from Wilshire, the FBI at last discovered for itself first the fact that Mihdhar had had a U.S. entry visa in 2000, then the fact that he had just very recently returned to the country. Only after that, in late August, did the FBI begin to search for Mihdhar and Hazmi—a search that was to prove inept, lethargic, and ultimately ineffectual.

An eight-member 9/11 Commission team was to reach a damning conclusion about the cable from CIA officer “Michelle” stating that Mihdhar’s travel documents had been passed to the FBI. “The weight of the evidence,” they wrote, “does not support that latter assertion.” The Justice Department inspector general also found, after exhaustive investigation, that the CIA had failed to share with the FBI two vital facts—“that Mihdhar had a U.S. visa and that Hazmi had travelled to Los Angeles.”

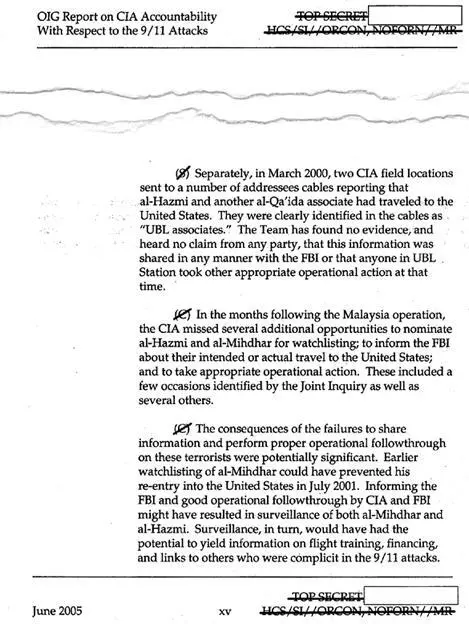

In 2007, Congress forced the release of a nineteen-page summary of the CIA’s own long-secret probe of its performance. This, too, acknowledged that Agency staff neither shared what they knew about Mihdhar and Hazmi nor saw to it that they were promptly watchlisted. An accountability board, the summary recommended, should review the work of named officers. George Tenet’s successor as CIA director, Porter Goss, however, declined to hold such a review. There was no question of misconduct, he said. The officers named were “amongst the finest” the Agency had.

THE EXCUSE for such monstrous failures? According to the CIA’s internal report, the bin Laden unit had had an “excessive workload.” Director Tenet claimed in sworn testimony, not once but three times, that he knew “nobody read” the cable that reported Hazmi’s actual arrival in Los Angeles. Wilshire, the officer repeatedly involved, summed up for Congress’s Joint Inquiry: “All the processes that had been put in place,” he said, “all the safeguards, everything else, they failed at every possible opportunity. Nothing went right.”

There are those who think such excuses may be the best the CIA can offer to explain a more compromising truth. “It is clear,” wrote the author Kevin Fenton, an independent researcher who completed a five-year study of the subject in 2011, “that this information was not withheld through a series of bizarre accidents, but intentionally.… Withholding the information about Mihdhar and Hazmi from the FBI makes sense only if the CIA was monitoring the two men in the U.S. itself.”

That notion is not fantasy. The CIA’s own in-house review noted that—had the FBI been told that the two future hijackers were or might be in the country—“good operational follow-through by CIA and FBI might have resulted in surveillance of both Mihdhar and Hazmi. Surveillance, in turn, would have had the potential to yield information on flight training, financing and links to others who were complicit in the 9/11 attacks.”

The CIA kept to itself the fact that it knew long before 9/11 that two of the future hijackers—known to be terrorists—had U.S. visas, and that one had definitely entered the United States

.

If the FBI had known, then–New York Assistant Special Agent in Charge Kenneth Maxwell has said, “We would have been on them like white on snow: physical surveillance, electronic surveillance, a special unit devoted to them.” After 9/11, and when the CIA’s omissions became known, some of Maxwell’s colleagues at the FBI reacted with rage and dark suspicion.

“They purposely hid from the FBI,” one official fulminated, “purposely refused to tell the FBI that they were following a man in Malaysia who had a visa to come to America.… And that’s why September 11 happened.… They have blood on their hands. They have three thousand deaths on their hands.”

Could it be that the CIA concealed what it knew about Mihdhar and Hazmi because officials feared that precipitate action by the FBI would blow a unique lead? Did the Agency want to arrange to monitor the pair’s activity? The CIA’s mandate does not allow it to run operations in the United States, but the prohibition had been broken in the past.

The CIA had on at least one occasion previously aspired to leave an Islamic suspect at large in order to surveil him. When 1993 Trade Center bomber Ramzi Yousef was located in Pakistan two years later, investigative reporter Robert Friedman wrote, the Agency “wanted to continue tracking him.” It “fought with the FBI,” tried to postpone his arrest. On that occasion, the FBI had its way, seized Yousef, and brought him back for trial.

With that rebuff fresh in the institutional memory, did the CIA decide to keep the sensational discovery of Mihdhar’s entry visa to itself? Or did it, as some Bureau agents came to think possible, even hope to recruit the two terrorists as informants?

The speculation is not idle. A heavily redacted congressional document shows that, only weeks before Mihdhar’s visa came to light, top CIA officials had debated the lamentable fact that the Agency had as yet not penetrated al Qaeda: “Without penetrations of OBL organization … [redacted lines] … we need to also recruit sources inside OBL’s organization. Realize that recruiting terrorist sources is difficult … but we must make an attempt.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Eleventh Day» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.