Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Eleventh Day

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Eleventh Day: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Eleventh Day»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Eleventh Day — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Eleventh Day», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

CIA OFFICIALS had briefed candidate George Bush and his staff on the terrorist threat two months before the election, bluntly warning that “Americans would die in terrorist acts inspired by bin Laden” in the next four years. In late November, after the election but while the result was still being contested, President Clinton authorized the Agency to give Bush the same data he himself was receiving.

The election once settled, Vice President–elect Cheney, Secretary of State–designate Colin Powell, and National Security Adviser–designate Condoleezza Rice received detailed briefings on bin Laden and al Qaeda. “As I briefed Rice,” Clarke recalled, “her facial expression gave me the impression she had never heard the term before.” Asked about that, Rice said acidly that she found it peculiar that Clarke should have been “sitting there reading my body language.” She told the 9/11 Commission that she and colleagues had in fact been quite “cognizant of the group.” Clarke, for his part, claimed most senior officials in the incoming administration did not know what al Qaeda was.

Clinton’s assistant secretary of defense for special operations, Brian Sheridan, told Rice that al Qaeda was “not an amateur-type deal … It’s serious stuff, these guys are not going away.” Rice listened but asked no questions. “I offered to brief anyone, anytime,” Sheridan recalled. No one took him up on the offer.

The Commission on National Security, which had been at work for two and a half years, was about to issue a final report concluding that an attack “on American soil” was likely in the not-too-distant future. “Failure to prevent mass-casualty attacks against the American homeland,” the report said, “will jeopardize not only American lives but U.S. foreign policy writ large. It would undermine support for U.S. international leadership and for many of our personal freedoms, as well.… In the face of this threat, our nation has no coherent or integrated government structures.”

So seriously did Commission members take the threat that they pressed to see Bush and Cheney even before the inauguration. They got no meeting, however, then or later.

Bush, for his part, met with Clinton at the White House. As Clinton was to recall in his 2004 autobiography, he told the incoming president that Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda would be his biggest security problem.

Bush would tell the 9/11 Commission he “did not remember much being said about al Qaeda” during the briefing. In his 2010 memoir, he dealt with the subject by omitting it altogether. According to Clinton, Bush “listened to what I had to say without much comment, then changed the subject.”

TWENTY-SIX

“WE ARE NOT THIS STORY’S AUTHOR,” GEORGE BUSH TOLD THE American people in his inaugural speech on January 20, 2001. God would direct events during his presidency. “An angel,” he declared, citing a statesman of Thomas Jefferson’s day, “still rides in the whirlwind and directs this storm.”

In the months and years since the whirlwind of 9/11, statesmen, intelligence officers, and law enforcement officials have assiduously played the blame game, passed the buck, and—in almost all cases—ducked responsibility. No one, no one at all, would in the end be held to account.

The Clinton administration’s approach, Condoleezza Rice has been quoted as saying, had been “empty rhetoric that made us look feckless.” The former President, for his part, staunchly defended his handling of the terrorist threat. “They ridiculed me for trying,” Clinton said of Bush’s people. “They had eight months to try. They did not try.”

“What we did in the eight months,” Rice riposted, “was at least as aggressive as what the Clinton administration did.… The notion [that] somehow for eight months the Bush administration sat there and didn’t do that is just flatly false.”

Quite early in the presidency, according to Rice, Bush told her: “I’m tired of swatting at flies.… I’m tired of playing defense. I want to play offense. I want to take the fight to the terrorists.” Counterterrorism coordinator Clarke, who was held over from the Clinton administration, recalled being sent a presidential directive to “just solve this problem.”

The record shows, however, that nothing effective was done.

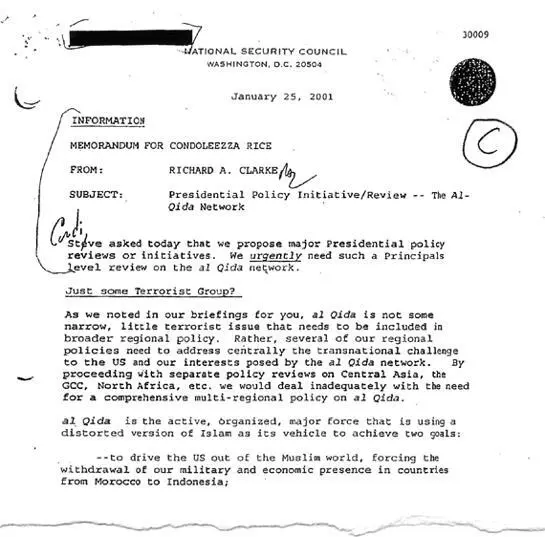

JUST FIVE DAYS after the inauguration, Rice received a memorandum from Clarke headed “Presidential Policy Initiative/Review—the al Qaeda Network.” It had two attachments, a “Strategy for Eliminating the Threat” worked up especially for the transition to the new administration, and an older “Political-Military” plan that had the same aim.

Al Qaeda, the memo stressed, was “not some narrow little terrorist issue.” It was an “active, organized, major force.… We would make a major error if we underestimated the challenge al Qaeda poses.” A meeting of “Principals”—cabinet-level members of the government—Clarke wrote, was “urgently” required. The italicization and the underlining of the word “urgently” are Clarke’s in the original.

Suggestions for action aside, the material said al Qaeda had “multiple, active cells capable of launching military-style, large-scale terrorist operations,” that it appeared sleeper agents were active within the United States. It proposed an increased funding level for CIA activity in Afghanistan. It asked, too, when and how the new administration would respond to the attack on the USS Cole —the indications, by now, were that al Qaeda had indeed been responsible.

Condoleezza Rice would claim in testimony to the 9/11 Commission that “No al Qaeda plan was turned over to the new administration.” Nor, she complained, had there been any recommendation as to what she should do about specific points. The staff director of Congress’s earlier Joint Inquiry into 9/11, Eleanor Hill—a former inspector general at the Defense Department—was shocked to hear Rice say that.

“Having served in government for twenty-some years, I was horrified by that response,” Hill said. “She is the national security adviser. She can’t just sit there and wait.… Her underlings are telling her that she has a problem. It’s her job to be a leader and direct them … not to sit there complacently waiting for someone to tell her, the leader, what to do.”

Within a week of President Bush’s inauguration, counterterrorism coordinator Clarke called for top-level action. By 9/11, eight months later, none had been ordered

.

The Clarke submission had in fact made a series of proposals for action. The pressing request, however, was for the prompt meeting of cabinet-level officials. Far from getting it, Clarke found that he himself was no longer to be a member of the Principals Committee. He was instead to report to a Committee of Deputy Secretaries. There were to be no swift decisions on anything pertinent to dealing with al Qaeda.

Though candidate Bush had declared there should be retaliation for the Cole attack, there would be none. Rice and Bush wanted something more effective, the former national security adviser has said, than a “tit-for-tat” response. By the time the Bush team took over, she added, the attack had become “ancient history.”

As for the deputy secretaries, they did not meet to discuss terrorism for three full months. When al Qaeda was addressed, at the end of April, Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz was deprecatory about the “little terrorist in Afghanistan.” “I just don’t understand,” he said, “why we are beginning by talking about this one man bin Laden.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Eleventh Day» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.