‘How is the spirit of the local people holding up?’

‘They’re a tough lot, the Maltese,’ the soldier conceded. ‘Not one word about surrendering or even seeking terms from any of ’em. They’re ready to follow the old boy right to the end. He fights alongside them, shares the dangers, and only allows himself to eat what they do. So he’s their hero. Here we are, sir.’

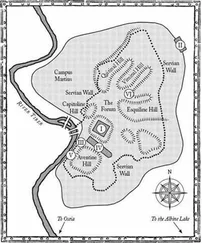

The soldier indicated the shell of a large building across an open expanse of rubble-strewn ground and with a start Thomas realised that he was looking across what had once been the neat lines of Birgu’s main square. They picked their way over to the entrance of the merchants’ guildhouse, stopping once to duck down as a cannonball moaned overhead. They listened for the crash of the impact but it never came.

‘Overshot,’ the soldier said with satisfaction.

They stood up and hurried across the square. A sentry at the guildhouse door recognised the soldier and he waved them through. Beyond the wide arch of the doorway was the hall where the island’s merchants and cargo-ship owners had met to do business. Windows high up in the walls had once illuminated the whitewashed plaster walls upon which hung portraits of the most influential of the guild’s members. Now the flagstone floor was covered with dust and grit, and where the roof had fallen in, shattered roof tiles lay in heaps. The soldier led Thomas across the hall to where stairs led down into the storerooms beneath the building. A corridor stretched out on both sides at the bottom of the stairs and was illuminated by candles guttering in iron holders mounted on the walls.

‘You’ll find the Grand Master down at the end.’ The soldier pointed to the left.

Thomas nodded his thanks and the soldier turned to the right to join a small group of men sitting at a table, drinking and playing dice. Arched openings lined the corridor and as Thomas passed by, he could see that some were being used to treat the wounded.

Others were filled with weapons, armour, powder kegs and small baskets of ammunition for arquebuses. A short distance down the corridor Thomas saw that a hole had been knocked through the wall and a stretch of tunnel led to the cellar of another building. There was an open space where a number of tables had been set up. Two men sat at one table upon which a map of the island was spread.

By the gloomy light of the candles Thomas could make out the features of Romegas in urgent conversation with a thin man with a matted white beard. It was a moment before he recognised the Grand Master. La Valette looked up at the sound of footsteps and he smiled wearily as he waved Thomas towards a stool beside the table.

Romegas nodded a greeting. ‘I’m glad to see you again, Sir Thomas. I feared the worst when I heard of your injuries. You were lucky to escape from St Elmo at the end.’

Thomas sensed a hint of criticism in the man’s tone and indicated the scarring on his face. ‘You have a singular view of what constitutes luck.’

Romegas shrugged. ‘ You and a handful of men survived, when all others were killed. I would call that luck, for want of another word.’

Thomas felt his anger stirring. ‘And which word would that be? What exactly would you accuse me of?’

The Grand Master cleared his throat. ‘Gentlemen, please, that’s enough. There are too few of us left to waste our efforts on petty fractiousness. That is why I summoned you from the infirmary, Thomas. I need every man who still has the strength, and the heart, to fight the Turks. We have lost so many good men, including my own nephew, and Fadrique, the son of Don Garcia. At least your squire still lives. He has proved to be a fine warrior, as brave as they come.’ He smiled briefly before his expression became sombre once again. ‘You two are the last of my advisers. Save all your anger for the enemy.’

Thomas was shocked. ‘Just the three of us? I know about Stokely, but Marshal de Roblas?’

Romegas stroked his creased brow. ‘He was shot through the head several days ago. But you would not have been aware of that, Sir Thomas. Much has happened while you were recovering from your wounds. Birgu and Senglea came under attack soon after St Elmo fell. You have seen the damage done to the town, but let me tell you that the wall is largely a ruin, destroyed by bombardment and the mines dug by the enemy’s engineers. Only the bastions still withstand the enemy’s guns. We have built an inner wall but it is a poor defence that is barely ten feet high, and there are no more than a thousand men left to hold the Turks at bay. Most of our soldiers are wounded and all of them are exhausted and hungry. Our powder is running short and there is still no sign of the relief force Don Garcia promised us.’

Thomas pursed his lips. ‘If it is as bad as that then we shall surely be defeated.’

‘No, Don Garcia will come,’ La Valette said firmly. ‘My good friend Romegas is inclined to dwell on our difficulties at the expense of our opportunities. Our situation is bleak but it is only half the picture. We know that the enemy camp is wracked with sickness and their spirits are at a low ebb because of the heavy losses they have endured since the siege began. And now the season is changing and the rain has come to add to the enemy’s discomfort. If we can hold Mustafa Pasha back for a little longer, he will be forced to quit the island before autumn sets in.’ He paused and narrowed his eyes shrewdly. ‘If I were the enemy, I would throw everything into one final assault, whatever the cost.’

‘Why?’ asked Romegas.

‘Because I would know that my master, the Sultan, would not be merciful if I were forced to return to Istanbul having failed to carry out his orders. I would do anything to keep my head on my shoulders. Therefore I believe Mustafa Pasha will attack us with all his might very soon.’ La Valette looked at his surviving advisers. ‘When the Turks come, they will be more desperate than ever to wipe us out. We shall need to be more than their equal in determination, or else they will slaughter every man, woman and child in Birgu.’

‘There is something else we could do,’ Romegas said quietly. ‘We still have St Angelo. We can defend that, even if we can’t hold

Birgu. Sir, I suggest we withdraw what is left of our fighting men into the fort. We can hold out there for a month or so yet, until Don Garcia and his army, or autumn, arrives.’

Thomas shook his head. ‘What about the civilians? We couldn’t possibly fit them all into the fort. Are you suggesting that we abandon them to the Turks?’ He thought of Maria and turned to his commander. ‘Sir, we can’t do that.’

‘We might have to,’ Romegas insisted. ‘How else can we make our supplies last long enough? The people are already starving. Our men will not have the strength to fight on in a few weeks’ time. The fort is more readily defended than the town and wall. It makes sense. It might be our only chance to save the Order, sir.’

‘Only at the price of our reputation,’ Thomas retorted. ‘Our name will go down in the annals of infamy if we leave the people to the mercy of the Turks. There will be no mercy, just massacre.’ Romegas smiled coldly. ‘This is war, Sir Thomas. A war that I, and the Grand Master, have been fighting through all the years we have served the Order. What matters, above all, is the survival of the Order.’

‘I thought that what matters is stemming the tide of Islam,’ Thomas countered.

‘While we live on we will always be the sword thrust into the side of the enemy,’ Romegas replied. ‘To ensure that, we must be prepared to make sacrifices. For the greater good.’

Thomas saw the strained expression on the Grand Master’s face as he reflected on Romegas’s suggestion and gave his response. ‘It’s true. We could hold St Angelo far more easily than Birgu, and perhaps long enough to see out the siege . . . And yet, what Sir Thomas says is also true. We should never forget that the Order was set up to protect the righteous and the innocent.’ He thought for a moment and then sighed. ‘I think I already know what I must do. Yes, I am certain of it.’

Читать дальше